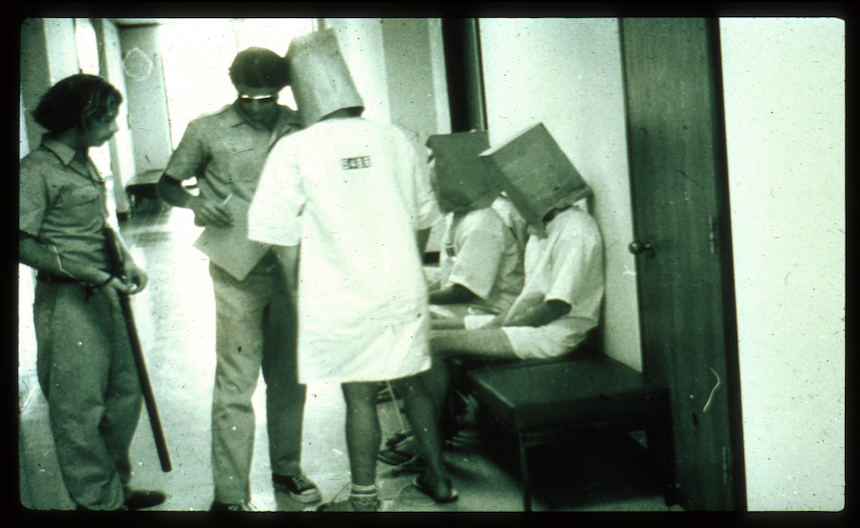

“The line between good and evil is permeable and almost anyone can be induced to cross it when pressured by situational forces.”

—Phil Zimbardo

No one reading this article conducts research with the intent to cause harm to others. It’s hard to imagine that anyone would—research is more regulated now, and those egregious stories of unethical work are a thing of the past, right? In fact, unethical research happens today despite protections that have been put in place to protect participants, and even despite researchers’ good intentions.

The classic example is Phil Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment. Zimbardo had the noble goal of understanding why good people do evil things, but his study had to be stopped after six days because it was causing good people to do evil things. How do well intentioned researchers end up conducting studies that seem so obviously unethical?

What Is Ethical?

If researchers can be unethical despite their best intentions, how can we understand what being ethical means in the first place? Can we even draw a line between ethical and unethical research, and even if we could, how would we know if we crossed it?

The fact is, ethics aren’t a simple set of rules we can just apply to our research, but involve deep, ongoing evaluation and negotiation. For example, the ethical question of what is “public” and free for study without participant consent, which is making headlines these days because of controversies over big data, has always been debated among ethnographers and user researchers. Is it necessary to obtain the consent of unaware participants in research in public spaces (Waern, 2016) or in social network experiments like the Facebook “emotional contagion” study (Kramer, Guillory & Hancock, 2014)?

“Big data” amplifies big questions of data ownership and anonymization of data collected from public sites. Recently, researchers in two separate studies scraped thousands of user profiles from OKCupid (Kirkegaard & Bjerrekær, 2014) and Facebook (Lewis, et-al, 2008) to do large scale analysis on user tastes and preferences, then shared the data sets. People were unaware that they were “subjects” of this research, and because their identities were not sufficiently anonymized, they were vulnerable to identification.

Facebook has rightly been heavily criticized in academic and popular forums (e.g., Zimmerman, 2010), and in response, the company removed public access to the dataset and has established a substantial in-house Institutional Review Board (IRB) that evaluates research proposals (Jackman & Kanerva, 2016). By contrast, Emil OW Kirkegaard, the researcher in the OKCupid study, continues to maintain that the data is public and no ethical issues are at stake, despite public criticism (Hacket, 2016). But is sharing your sexual preferences on a dating website any different from having a conversation in a public space? Does it really matter if the researcher scraped thousands of those preferences from website rather than overhearing them in a cafe?1

Of course, splashy headlines aside, data scientists are hardly alone in committing ethical offenses. Research with vulnerable populations, including ethnographic research, has particular potential for harm. Anthropologists and other social scientists continue to grapple with the dangers of interpreting what we observe through our own lens of values and experiences. Significant power differentials, for example between “first world” researchers and indigenous peoples, amplify the influence of the research itself, as well as its outcomes and legacies. Issues like informed consent, which at first blush seem straightforward, continue to confound: is adequate informed consent even possible in radically different cultural and social contexts, with populations whose language the researcher does not speak, who have low or no literacy, or don’t understand the technology being used in the study (here’s an example)? The situation is made worse when companies bury informed consent language into non-disclosure agreements, creating lengthy legal documents that neither the researcher nor the participants can fully understand regardless of one’s language spoken or literacy level.

Why You Should Care

Unethical research continues to happen for a whole spectrum of reasons, and to tackle them, it’s critical for our community to make ethics a priority. We invite you to add your voice to our initiative to develop our own EPIC ethical guidelines (here in draft form). Once adopted by the EPIC Board, all members and anyone submitting to the annual conference must adhere to these guidelines. We strongly believe it is important to promote and defend a set of ethical guidelines because:

- They are a manifestation of our values as a community and a reminder of what we stand for.

- We have a responsibility to educate members of our community who didn’t get a foundation in research ethics as part of their training.

- Our community has an obligation to protect participants in our studies.

- Our community has an obligation to put everyone on equal footing. Some fascinating research findings can be obtained when you are not bound to certain ethical guidelines. When reviewing submissions for our conference, it is not fair to compare studies when one researcher is bound to certain limitations while another is not.

- We should publicly disassociate ourselves from unethical research.

- Our community should feel confident that the research we support and reference has been ethically obtained.

Call to Action

We invite you to add your comments below and in the proposed guidelines. We will post an update here following the workshop to share everyone’s position papers and the notes so the discussion can continue discussion among our international community.

Note

In 2013, the government proposed the (CFAA) which would, among other things, criminalize the act of research scraping public data from websites for this type research; however, it would also stop researchers from investigating companies’ potentially harmful business practices (e.g., showing higher interest rates to users they know or suspect are minorities. As a result, the ACLU is challenging this law. A law that may seem on the surface to protect individuals of a website can in fact equally protect a business that is harming its users.

References

American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) (June 29, 2016) “ACLU Challenges Law Preventing Studies on ‘Big Data’ Discrimination”

Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) (April 24, 2013)

Hacket, R. (May 18, 2016). “Researchers Caused an Uproar by Publishing Data From 70,000 OkCupid Users.” Forbes

Jackman, M., & Kanerva, L. (2016). Evolving the IRB: Building Robust Review for Industry Research. Washington and Lee Law Review Online,72(3), 442.

Kirkegaard, E., & Bjerrekær, J.D. (2014). The OKCupid Dataset: A very Large Public Dataset of Dating Site Users. Open Differential Psychology. [Originally posted at https://osf.io/p9ixw/]

Kramer, A. D., Guillory, J. E., & Hancock, J. T. (2014). Experimental Evidence of Massive-Scale Emotional Contagion through Social Networks. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(24), 8788-8790.

Leetaru, K. (JUN 17, 2016). “Are Research Ethics Obsolete In The Era Of Big Data?” Forbes.com

Lewis, K., Kaufman, J., Gonzalez, M., Wimmer, A., & Christakis, N. (2008). Tastes, Ties, and Time: A New Social Network Dataset Using Facebook.com. Social networks, 30(4), 330-342.

Ngaruiya, C.M. (Dec 16, 2015) “Mama, do I have your consent?”

Waern, A. (2016, May). The Ethics of Unaware Participation in Public Interventions. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 803-814). ACM.

Zimbardo, P. G., Haney, C., Curtis Banks, W., & Jaffe, D. (1972). Stanford Prison Experiment: A Simulation Study of the Psychology of Imprisonment. Philip G. Zimbardo, Incorporated.

Zimmer, M. (2010). “But the Data Is Already Public”: On the Ethics of Research in Facebook. Ethics and information technology, 12(4), 313-325.

Related

Ethics in Business Anthropology, Laura Hammershøy & Thomas Ulrik Madsen

Ethnographer Diasporas and Emergent Communities of Practice: The Place for a 21st Century Ethics in Business Ethnography Today, Inga Treitler & Frank Romagosa

Making Silence Matter: The Place of the Absences in Ethnography, Brian Rappert

0 Comments