Work

By understanding work as social practices with cultural meaning, we can create more positive organizations, employment experiences, and interactions between individuals and systems.Overview

Work as a focus of ethnography covers a broad range of domains and topics, opening the door to question such as the nature of work itself, including paid and unpaid labor; changes driven by advances in technology or major social disruptions such as the COVID-19 pandemic; how productivity, innovation, and creativity are defined and performed through work practices; the nature of automation and human-machine interaction; the work we do as ethnographers and researchers; and much more.

Organizations are by nature amalgams of complex social infrastructures, involving performative displays in an environment that is constantly evolving due to changes in people, technology, policy, and wider social flux. Even as observers, researchers become a part of that interplay, which inspires reflection on both the work we study and our approaches to the work we do. This collection brings together papers, perspectives, and PechaKucha presentations that explore the dynamics of work within organizations and the complexities of interactions between individuals and systems.

As ethnographers, we look at work with an eye toward constructs such as ritual, discourse, embodiment, and routinization. These enable us to see deeper into the meaning, not only of the work itself, but of the interactions between the people who do the work. It raises the work beyond the mundane and into its place as a fundamental part of our social fabric.

Key Articles

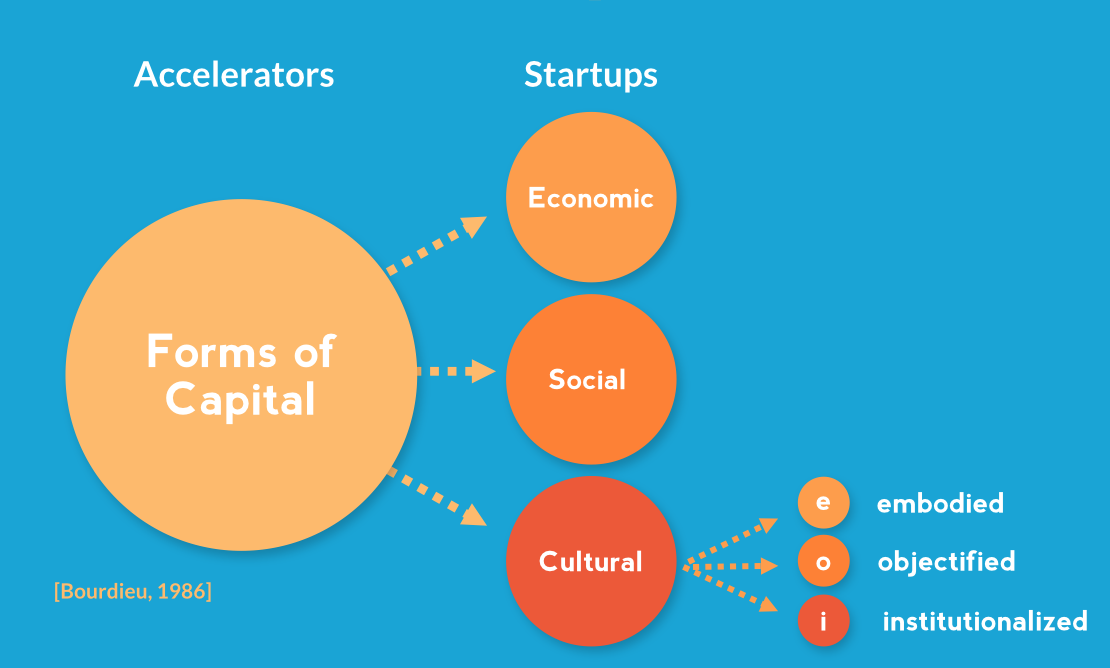

The Ritual of Lean, Julia Katherine Haines (2014). This article shows how social ritual lies at the core of productivity, innovation and product development processes. In the case of Lean StartUp, she argues that focused rituals to create meaning and shared understanding can shift toward a rote repetition of process. This ritualization loses the meaning and value originally inherent in those practices. In so doing, she asks ethnographers to take a close look at our own practices and to question where ritualization may have positive and negative effects on work.

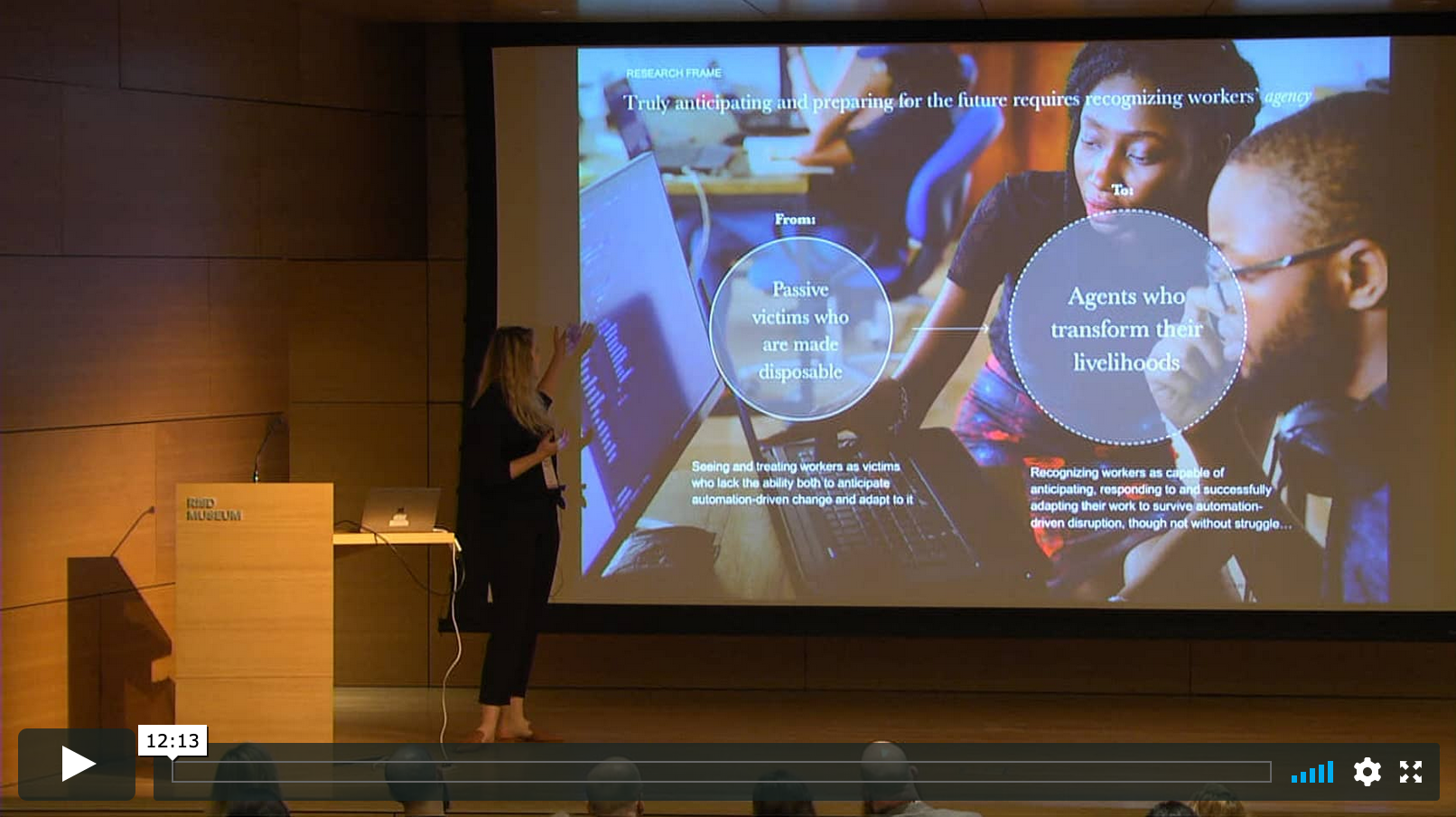

The Adaptation of Everyday Work in an Age of Automation, Tamara Moellenberg, Morgan Ramsey-Elliot, and Claire Straty (2019). The authors tackle the interactions between people and technology, in particular the human quest for agency in the face of job automation. They point to the challenges workers face in ensuring that others see the value of the human aspects of the work, noting that “the ardor and frequency with which these agents and medical technicians talked to our researchers about how they saw their work, and what terms they used to describe it, is a testament to the fact that they were not yet comfortable that others see it the same way.” The authors emphasize that it is the ethnographer’s challenge to help others to see the work in this way.

Designing Good Jobs: Participatory Ethnography and Prototyping in Service-oriented Work Ecosystems, Marta Cuciurean-Zapan and Victoria Hammel (2019). The authors take on the question of employee agency in the face of technological disempowerment. They argue for ethnographers to become advocates for the workers they study, emphasizing that “[d]esigning better jobs requires involvement of staff beyond the duration of the project.” Analyzing research literature and three case studies, they advocate for understanding work as an ecosystem, and offer approaches for mapping technological potential and staff needs to reveal opportunities to design better jobs.

Bodywork and Productivity in Workplace Ethnography, Sam Ladner (2014). This PechaKucha speaks to the embodiment of work, showing how physical presence and contact create social bonds and help people cope with change. She argues for the importance of gaining a shared perspective through physically shared experiences, and, in a forward-looking conclusion, wonders how this will translate through increasingly technology-mediated interactions. Since this presentation was recorded, of course, technology-mediated interactions have become the norm in many professional fields, requiring us to even more consciously consider bodywork and its alternatives in the workplace.

Beyond Zoom Fatigue: Ritual and Resilience in Remote Meetings, Suzanne Thomas, John Sherry, Rebecca Chierichetti, Sinem Aslan, and Luminita-Anda Mandache (2022). During COVID, when work in many fields was suddenly and forcibly moved away from the physical, the authors found that it is the social – not technological – aspects of collaboration that are most challenging. They frame meetings as rituals (and acknowledge that there are different kinds of rituals expressed in meetings) and present research demonstrating the importance of designing technology to support these interactions. They add that “In social science research more generally, seeing the process of ritualization in meetings might be useful for connecting detailed attention to the ways ritualization in meetings connects with broader questions of social scientific interest, including the complex relationship among technologies, professional identity formation and institutions or issues of diversity, equity and inclusion.” As ethnographers, we should not only consider how technology supports these rituals, but how these rituals evolve and change as the workplace changes.

Go Deeper

Should User Research be Funny?, Megan McGrath (2017). Capturing and analyzing occupational humor can enable researchers to gain deeper insight into the workplace. In this PechaKucha, Megan McGrath shows how jokes reveal pervasive truths and offers guidance on how to leverage humor in workplace studies.

Disrupting Workspace: Designing an Office that Inspires Collaboration and Innovation, Ryoko Imai and Masahide Ban (2016). Ryoko Imai and Masahide Ban’s Case Study focuses on how an internal ethnographic study to investigate how space was used by an R&D group led to the design of a new office space that facilitated collaboration and innovation for the group.

In Praise of Theory in Design Research: How Levi-Strauss Redefined Workflow, Bill Selman and Gemma Petrie (2017). Ethnographers draw on theory in our work, but rarely reveal this undercurrent in client or stakeholder presentations! Bill Selman and Gemma Petrie incorporated Levi-Strauss’s concept of bricoleur into discussion with stakeholders to shift their approach to workflows and highlight the different mental models of engineers and participants.

A Perfect Storm? Reimagining Work in the Era of the End of the Job, Melissa Cefkin, Obinna Anya, and Robert Moore (2014). Melissa Cefkin, Obinna Anya, and Robert Moore examine how peer-to-peer is transforming work, employment, and organizations. They focus on a marketplace, a crowd work system, and a crowdfunding experiment, all implemented within an enterprise, to explore how workplace culture is being reimagined.

Numbers May Speak Louder than Words, but Is Anyone Listening? The Rhythmscape and Sales Pipeline Management, Melissa Cefkin (2007). Melissa Cefkin focuses on talk in the context of sales meetings to explore how meaning is formed through everyday, routinized activities. In this paper she highlights how expression and performance are fundamental to creating meaning and significance in workplace interactions.

Back to the Future of Work: Informing Corporate Renewal, Jennifer Watts-Englert, Margaret Szymanski, Patricia Wall, Mary Ann Sprague, and Brinda Dalal (2012). Many years before the majority of workers were moved into remote work, Jennifer Watts-Englert, Margaret Szymanski, Patricia Wall, Mary Ann Sprague, and Brinda Dalal conducted a multi-year ethnographic study on how emerging technologies were being incorporated into work. While those technologies are no longer emergent, their insights into how people adapt to the changing nature of work remain essential for meeting new challenges.

Curator: Alexandra Mack

Contributor: Elizabeth Anderson-Kempe