This paper integrates arts-based methodologies into research and design, bringing new ways of knowing to the complex socio-ecological challenges we face today. New findings demonstrating that cognition is deeply rooted in bodily and social interactions highlight the need to shift our focus from the mind to the body. The authors provide a conceptual foundation and detailed instructions for practicing Social Presencing – which focuses on social dynamics – and Warm Data, which focuses on interrelationships within systems. Outcomes for participants included a clear evolution from stagnation and conflict to greater connection and potential for collective action, and the ability to face complex problems with a more collaborative perspective.

1. Introduction

This paper explores the combination of two methodologies—Social Presencing Theater (SPT) and Warm Data—to understand complex social systems and challenge traditional ways of knowing in ethnography and design. The combined methodology invites us to shift from a “systems thinking” perspective to a “systems sensing” experience to prepare for addressing global socio-ecological challenges. There are several reasons why combining these methodologies is possible and valuable: first, both argue that the foundation of successful activity in the social field arises from an engagement with the world and the back-and-forth interactions between the expert’s “know-how” and the people’s “know-what,” sketching out a collective embodied approach. Second, they emphasize that meaningful action requires a deep change in perception as well as stronger social bonds among the actors involved; the dynamic relationship that emerges, as Shove, Pantzar, and Watson (2012) argue, reconstitutes the meaning of social practice.

In the face of global socio-ecological crises, traditional methodologies have proven inadequate in addressing the complexity of “wicked problems” (Buchanan, 1992). These challenges demand inter-systemic changes rather than sectorial solutions. Modern approaches to addressing these problems often lead to repeated errors or simplification of the necessary complexity, usually acting as corrections of behaviors instead of questioning what has caused human perception changes. Thus, there is a growing need to shift from linear strategies to more holistic, embodied, and relational approaches. As ethnographers and designers, we need to uncover new strategies to collectively act based on a shared, deep, and first-hand understanding of the world, while shortening the gap between non-expert and expert thought—enabling connections between clients, researchers, and the external world (Roberts & Hoy, 2015).

At the heart of the expert ethnographer, there is always a practical expression that emerges from a set of techniques, theories, and heuristics that provide sophisticated cultural analysis and interpretation, which is later shared through communication tools, acts, and artifacts designed to influence, inform, and impact multiple audiences (Arnal & Holguin, 2007).

In this context, SPT, an embodied social arts-based methodology developed by the American-Japanese dancer Arawana Hayashi (Hayashi & Scharmer, 2021), has been used in multiple sectors and organizations to support processes of change. This approach is based on her extensive experience in oriental embodied practices across various social contexts combined with insights from Otto Scharmer’s “Theory U” principles (Scharmer, 2018) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) which explores system thinking-sensing, organizational learning, and action research. SPT can be seen as an embodied collaborative tool that supports the possibility of achieving significant change and fostering connections among participants by applying deep listening practices, activating bodily wisdom to access the sensing world and transcending their narratives to described reality (Littlewood & Roche, 2004).

It is important to understand the meaning of the word “theater” in SPT practice: it derives from the Greek theatron, a ‘place of viewing,’ and from thesthai, ‘to behold.’ It is essentially about making something visible, which takes us to the visual design field expertise, linking aesthetic and composition principles that guide the analysis to describe relationships created between the parts (shapes, materials, gestures, and bodies of individuals) and the whole (social body) to communicate and understand the essential quality of the practice.

In her book, Nora Bateson (2023) emphasizes that to improve our interaction with the world, we must first enhance our perception of the complexity we live within. Her concept of Warm Data, the other methodology we wish to combine, seeks to maintain the integrity of relational contexts within systems, providing a richer, more nuanced understanding of complex phenomena. Warm Data conversations capture qualitative dynamics and offer insights that quantitative data alone cannot provide, emphasizing the importance of interrelationships and contextual interdependencies, which are crucial for effectively addressing systemic challenges within living systems.

In this paper, we will outline how these methodologies, when applied across disciplines like dance, theater, architecture, and poetry, generate a sensory understanding and foster inter-systemic changes for various collectives (Hayashi & Scharmer, 2021). In the next section, we describe our combined methodology from a conceptual perspective. Afterwards, we provide detailed instructions for practitioners to apply it in their respective contexts. We also describe a workshop exercise in which the methodology was successfully applied. Finally, we discuss the workshop’s results and provide general conclusions about efforts to combine methodologies in our practice.

2. Conceptual Foundations of the Combined Methodology

To understand SPT, we need to go back to the enactive approach to cognition. SPT proposes that cognition is deeply rooted in the dynamic interactions between the organism and its environment (Di Paolo, 2021; Di Paolo & De Jaegher, 2012, 2022; Sepúlveda-Pedro, 2024). It emphasizes autonomy, sense-making, emergence, embodiment, and experience. This approach holds that cognition emerges from the adaptive preservation of a dynamic network of sensorimotor structures sustained by continuous interactions with the environment and the body. By integrating the enactive cognition approach into ethnographic methods, researchers can recognize that understanding social and cultural dynamics requires more than observation and verbal analysis. It is essential to acknowledge that many cultures have long recognized the central role of the body in social dynamics—a recognition that Western thought has often overlooked. With SPT, we are now seeking to reclaim and integrate this understanding into our current context. The more we dive into these types of practices by exploring and expressing social experiences through embodied practices, the more genuine and powerful they become.

As a non-verbal arts-based methodology, SPT uses embodied practices to explore social dynamics and systemic challenges. It facilitates the perception and manifestation of social relationships and dynamics through body movements and group presence. Among the tools used to bring transformative innovation and change to organizations and institutions, SPT creates a new language that allows participants to shift their interaction from rational to emotional and express blockages (Stucks) and transitions (Shifts) within systems, fostering a deeper understanding of social fields and their dynamics. We emphasize the importance of embodied presence, movement, and collective inquiry drawn by this technique. When focusing on bodily sensations and the experience of being part of a dynamic social body, participants are able to infer collective responses and envision future possibilities of any given situation. This set of embodied practices transcends language barriers and activates individual and collective consciousness, making it a powerful tool to address socio-ecological challenges.

On the other hand, Warm Data is defined as information derived from deep conversations about the interrelationships that connect the elements of a complex system. This type of data is trans-contextual because it captures the qualitative dynamics and relational patterns within a living system. Warm Data contrasts with traditional “cold” data by maintaining the context and interplay of system elements, which is essential for understanding and responding to complex challenges. By focusing on the relational and dynamic aspects of systems, it provides a more comprehensive and coherent understanding of the phenomena being studied (Bateson, 2023).

The Warm Data approach also integrates other domains in sciences, arts, and professional knowledge to create a qualitative inquiry into the integration of life. It challenges the mechanical reductionist view of environmental and social issues, promoting a more interconnected and relational perspective. This approach is particularly relevant for ethnographic research as it aligns with the enactive approach to cognition and resonance theory, both of which emphasize the importance of relationships and embodied experience in understanding complex systems.

We noticed that these two methodologies share a feature that can be best described with the concept of resonance. Resonance has a subjective and objective dimension, as it does not refer to cognition alone; it is also something that is felt and shared between the viewer and the viewed (Hayashi & Scharmer, 2021). Resonance awakens a sense and appreciation for the fullness of space, as seen in Hartmut Rosa’s (2019) work with resonance theory, which focuses on the quality of relationships and the mutual vibrant response between individuals and their environment. Resonance is characterized by a meaningful connection, unlike alienated relationships which are marked by disconnection and repulsion. Following Rosa’s suggestion on how to counteract the alienation caused by modern society’s constant acceleration and expansion, we believe that the combined techniques of SPT and Warm Data provide us with a robust methodology to understand and address the complexity of socio-ecological challenges.

The combination of a conversational approach (Warm Data) with an embodied social art (SPT) can be conceptually described by four essential qualities:

- Relationality and Dynamism: As an enactive approach, SPT emphasizes that human cognition is deeply situated in sociocultural contexts and that interactions within these contexts are dynamic and co-constitutive. Both the subject and the world it encounters emerge from dynamic relationships and interactions, not as a priori given entities. Using gestures, movements, and brief sentences to express oneself opens dimensions to the quality of connection one can achieve, which is profound but not textual in nature.

- Embodied Cognition: An embodied set of practices such as SPT deals with the premise that cognition is not just a mental process but is embodied and manifested through physical interaction with the environment. Warm Data, on the other hand, is not just about what we say or express but what we inscribe in objects, artifacts, and matter. Our combination provides a theoretical basis to understand how resonant experiences are bodily lived and how physical interactions with the world contribute to a collective understanding of a complex situation.

- Relational Ontologies: By proposing this combined methodology, we suggest a relational ontological view where the subject and the world are co-original and mutually shape each other through processual performance. This emphasis on the co-constitution of mind and environment shows how interactions and relationships are fundamental to the formation of experience and knowledge.

- Conditions for Prototyping: Finally, we stress the importance of studying the social conditions that facilitate social change by providing analytical tools to investigate and explore how specific social and cultural structures enable or inhibit meaningful interactions. This provides a deeper understanding of the conditions that favor new ways of exploring and relating to today’s challenges.

We believe this combined approach can help ethnographers promote a more holistic and resonant understanding of social phenomena as complex living systems, fostering deeper connections and insights. It provides them with tools to explore new dimensions of reality and generate innovative responses to complex challenges. It also offers a powerful way to address the pressing socio-ecological crises of our time, moving towards healthier and more connected futures.

3. Applying the Combined Methodology

Applying our combined methodology means engaging participants in a series of performative practices to cultivate embodied awareness and social presence, followed by a structured conversation to gather data. The journey begins with the preparation and setting of the space for the stage. The main objective is to create an environment that encourages embodied exploration and deep conversation. It is better to have a spacious room bathed in natural light, where comfortable seating arrangements invite participants to relax and feel at home. A set of carefully designed SPT practices must be ready for use, and recording devices should be discreetly placed to capture the rich dialogues that will unfold, always with the participants’ consent. This setting welcomes a diverse group of participants—professionals, academics, students, and community members—each bringing their unique perspectives and energies.

Each session begins with a simple introduction to practices of simple movements for body and space awareness to set the tone. These practices are designed to help participants connect with their bodies and each other, grounding them in the present moment and preparing them for the journey ahead. The facilitators explain the goals and exercises of the session and introduce the theme or socio-ecological challenge to be attended.

After that, one of the practices we consider most appropriate for experimenting in organizational contexts is 4D Mapping. This practice consists of defining the specific situation to be addressed and identifying the main actors (usually in a preparatory session prior to the main session; the number of actors should not exceed 8 and must always include the Earth, the most vulnerable actor, and the one representing the highest future possibility). Participants then select their roles and engage in simple collective embodied arrangements, where they create a physical sculpture that represents a ‘stuck’ place or situation in the current state of the system. Afterwards, they are asked to slowly transition to a second sculpture representing a true move towards an ‘unstuck’ state. While Sculpture 1 is being formed, participants, acting in their roles, need to come up with a phrase that resonates with their role and enunciate it while taking their place in the sculpture. As Sculpture 2 is created, the participants develop another phrase, adding layers of meaning to the embodied exploration.

The session then transitions to an embodied conversation. This shift from embodied exploration to verbal articulation is gentle, allowing participants a few moments of silent reflection. Participants in the sculpture, as well as the observers, are invited to engage in a structured conversation guided by three main arguments: “What have you seen?”, “What have you felt?”, and “What have you done with your body?”. These prompts encourage participants to share their visual observations, emotional and bodily sensations, and physical actions and movements with a brief intervention instead of a long speech.

The exercise thus evolves from SPT enactment to Warm Data conversations, highlighting the importance of capturing relational and contextual information and registering them in various forms. One form of registration is through log diaries with trigger questions given to participants, which are answered in written form and shared during or after the session. Another type of registration is the graphic recording of the situation by a visual scriber. We also have the session recorded with audio and hand microphones for the main commenters that are later used for transcription, provided we have permission. Open-ended questions delve deeper into the relational dynamics and interdependencies observed during the SPT practices.

To conclude participants gather in a circle, discussing key learnings and insights. They are encouraged to consider how these insights can transform their personal and professional perceptions. The facilitators evocate the main themes and relational patterns that emerged during the conversation, encouraging participants integrate their experiences and carry forward the wisdom gained from the session.

This integrated methodology creates a holistic approach to understanding and addressing complex socio-ecological challenges. It not only deepens participants’ perception of the systems they inhabit but also fosters a sense of connection and possibility, essential for meaningful action in the face of global crises.

4. Applying the Combined Methodology—A Success Story

In June 2023, this combined methodology was applied at a workshop in the Global Business Anthropology Summit (GBAS) in Mexico City. This workshop brought together 36 participants from diverse backgrounds, including entrepreneurs, researchers, activists, business leaders, academics, and students. A brief summary of the experience can be found in (Bueno et al., 2023).

The session began with SPT practices. The facilitators guided participants through a 4D mapping exercise to depict the “stuck” state of consulting firms facing socio-ecological challenges and to envision a “better” future. Participant roles used for the session were: earth, indigenous girl, shareholders, employee consultant, citizen activist, public regulators, and media. Each participant embodied their role, creating physical sculptures that visually and kinesthetically represented the current and desired future state. As they held their poses, participants shared phrases that resonated with their roles, adding layers of meaning to the embodied exploration.

Several SPT practices include speaking, and the reflection and dialogues of each session are a vital part of the learning. The GBAS session could be analyzed from the perception of change in the emotional and mental state reflected by the phrases enunciated by the participants before starting sculpture 1 and after making sculpture 2. Those phrases, as well as place arrangements and gestures observed in the participants’ bodies, convey evidence of the transition experienced before and after the exercise. Below is a table comparing the phrases said by each role in the session:

Table 1. Two Stages in Phrases Enunciated by Participants

| Participant role | Before (sculpture 1) | After (sculpture 2) |

| Earth | “Keep going” | “I’m waking up” |

| Indigenous girl | “I can’t say nothing” | “I need help” |

| The best future possibility | “Please” | “There is a way” |

| Shareholders | “I can’t see” | “I want to share” |

| Employee consultancy | “Advise” | “Support” |

| Activist citizen | “Hang in here” | “Together” |

| Public regulators | “Let’s listen” | “Pay attention” |

| Media | “I won’t see” | “I listen to everyone and everything” |

The table shows the eight participant roles; the second column shows the phrases enunciated before making sculpture 1, and the third column on the right shows their final ones.

Following the physical exploration, the session transitioned into an embodied conversation. Participants were given a few moments of silent reflection to shift from physical to verbal articulation. They then engaged in a structured conversation guided by prompts such as “What have you seen?”, “What have you felt?”, and “What have you done with your body?”. These questions encouraged participants to share their visual observations, emotional and bodily sensations, and physical actions, helping to bridge the gap between their embodied experiences and verbal expressions.

The session concluded with a reflection and integration phase. Participants gathered in a circle, reflecting on the session and discussing key learnings and insights. They considered how these insights could inform their professional and personal practices. The facilitators summarized the main themes and relational patterns that emerged during the conversation, helping participants integrate their experiences and carry forward the wisdom gained from the session. The exchange evolved into a Warm Data discussion that captures relational and contextual information. Open-ended questions delved deeper into the relational dynamics and interdependencies observed during the SPT practices.

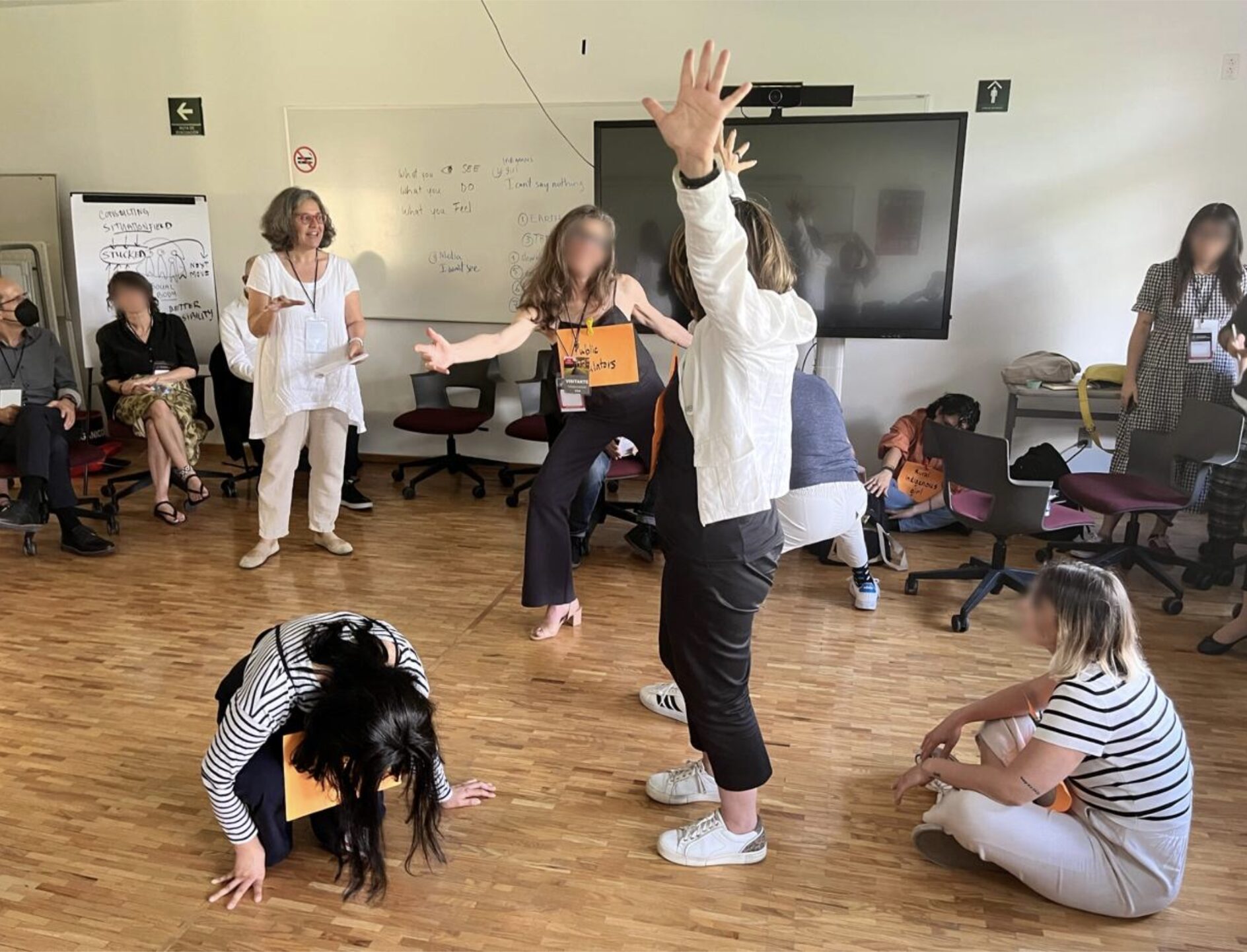

Figure 1. SPT ludic workshop session in June 2023 at GBAS Mexico City, facilitated by the authors.

This workshop and others we have conducted provide valuable insights into the potential of these methodologies to address complex socio-ecological challenges. The results demonstrate significant shifts in the emotional and mental state of participants, highlighting the effectiveness of integrating embodied practices with relational conversations.

The transition observed in the participants’ expressions before and after the SPT session reveals a profound impact on their perception and engagement with their roles. For example, the earth role transitioned from a state of relentless perseverance (“Keep going”) to a state of awakening and heightened awareness (“I’m waking up”). This shift signifies a deeper connection to the environment and an enhanced perception of the surrounding complexities, aligning with the group resonance and mutual responses between individuals and their environment.

Similarly, the Indigenous girl role moved from a sense of silence and inability to express (“I can’t say nothing”) to an acknowledgment of need and openness to seeking help (“I need help”). This change indicates greater vulnerability and willingness to connect, which are crucial for fostering genuine relationships and collaborative efforts, resonating with the enactive approach to cognition that emphasizes the importance of social interactions in sense-making (Di Paolo & De Jaegher, 2012).

The best future possibility role illustrated a transformation from uncertainty and supplication (“Please”) to clarity and optimism (“There is a way”). This shift reflects a newfound confidence in envisioning and pursuing concrete solutions, a critical aspect of addressing systemic challenges as suggested by Bateson’s concept of Warm Data, which seeks to maintain relational contexts and provide a nuanced understanding of complex phenomena (Bateson, 2023).

The shareholders who initially felt blocked and visionless (“I can’t see”) evolved towards a desire for openness and sharing (“I want to share”). This transition suggests a movement from isolation to collaboration, emphasizing the importance of inclusivity in tackling complex issues, which is consistent with the goals of SPT to foster embodied presence and collective inquiry (Hayashi & Scharmer, 2021).

The employee consultancy role demonstrated a shift from a distant advisory position (“Advise”) to active support and participation (“Support”). This change highlights an increase in empathy and commitment essential for effective collaboration and problem-solving, reinforcing the principles of enactive cognition that underline the embodied and relational nature of understanding (Di Paolo, 2021).

The citizen activist’s role transitioned from persistence in challenging circumstances (“Hang in here”) to a sense of unity and collective effort (“Together”). This shift underscores the power of collaboration and the importance of working together to overcome difficulties, also resonating with Rosa’s concept of resonance, which advocates for a collective response to the crises of modern society (Rosa, 2019).

Public regulators moved from a passive willingness to listen (“Let’s listen”) to a proactive call for conscious and attentive action (“Pay attention”). This evolution indicates a heightened sense of responsibility and alertness crucial for effective governance and regulation, which aligns with the theoretical emphasis on the dynamic and responsive nature of socio-ecological systems (Sepúlveda-Pedro, 2024).

Finally, the Media role showed a dramatic shift from refusal and resistance (“I won’t see”) to complete openness and willingness to listen to diverse perspectives (“I listen to everyone and everything”). This transition highlights the importance of inclusivity and understanding in media practices, essential for fostering a well-informed and empathetic society, which is a key tenet of Warm Data’s relational approach (Bateson, 2023).

6. Conclusion

Overall, the SPT and subsequent Warm Data sessions facilitated significant emotional and mental transitions from states of blockage, resistance, and isolation to states of openness, collaboration, and awareness. Participants exhibited a clear evolution from stagnation and conflict to a greater sense of connection, mutual support, and potential for collective action. These changes suggest a positive impact on individuals’ ability to face complex problems with a more integrative and collaborative perspective. The combined method not only brings clarity to nonverbal work but also sheds light on how we can communicate better collectively.

However, despite the promising outcomes, the implementation of this combined methodology presents certain challenges and limitations. The embodied practices involved in SPT can evoke strong emotions, which may be difficult to manage in some settings. Facilitators must be equipped to handle these emotional responses and provide a supportive environment for participants. Additionally, the dynamic and emergent nature of SPT and Warm Data conversations can lead to unpredictable outcomes. While this unpredictability is inherent to the process, it requires flexibility and adaptability from both facilitators and participants. Furthermore, incorporating these embodied and relational methodologies into traditional ethnographic practices may require a paradigm shift for researchers. It challenges the conventional focus on observation and verbal analysis, demanding a more holistic and embodied approach to understanding social phenomena. Therefore, it is crucial that facilitators possess all the necessary skills and capabilities to effectively implement these processes.

It is not debatable that the wellbeing of our planet is currently threatened by many crises, most of them manmade (Scarano, 2024). It is thus justified and fundamental that current changes are addressed collectively and with more diverse understandings of these complexities. New ways to approach data and to understand our presence in the world can emerge when we revisit and combine already existing methodologies.

The integration of SPT and Warm Data is a step toward a transformative approach to understanding and addressing complex socio-ecological challenges. This combined methodology could begin to shift the focus from the mind to the body and effectively integrate the context to a better understanding of social presence in relation to the system. The results from the workshop demonstrate that participants from different backgrounds and languages can experience significant awareness of their emotional and mental states, fostering deeper connections and encouraging a more holistic perception of their roles within systems.

The theoretical underpinnings of this approach are robust, drawing on enactive cognition and relational understanding to create a comprehensive framework for ethnographic research and practice. These theories highlight the importance of embodied experiences and relational dynamics, which are crucial for capturing the complexity of socio-ecological systems and fostering meaningful change.

However, the successful implementation of this combined methodology requires facilitators to possess a range of skills and capabilities to manage the emotional intensity and unpredictability inherent in these processes. Flexibility, adaptability, and a supportive environment are essential to navigate the dynamic nature of SPT and Warm Data conversations and to integrate these methodologies into traditional ethnographic practices effectively.

Finally, future research should continue to explore the applications of this integrated methodology in various contexts, refining the approach and evaluating its effectiveness in fostering systemic change. By embracing embodied experience and relational understanding, this methodology not only advances the field of ethnography but also proposes innovative forms of activism and social change, moving towards healthier and more connected futures.

About the Authors

Nora Morales is an academic from UAM Cuajimalpa, an information designer with a PhD in Social Sciences. She is careful to maintain curiosity about “mapping” tools to explore different realities and co-creation in this complex world. nmorales@cua.uam.mx

Blanca Miedes is an economist and researcher professor from Huelva University in Spain. She likes to think outside the brain, using the feelings and movements of our bodies in the physical space to comprehend more deeply and imaginatively. miedes@uhu.es

Note

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank Juliana Saldarriaga, our curator, for her commitment and dedication to this piece and all participants in the workshops that let us explore new ways to better connect to the essence of our humanity.

References

Arnal, Luis, and Roberto Holguin. 2007. “Ethnography and Music: Disseminating Ethnographic Research inside Organizations.” In Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings 2007, pp. 201–213. https://www.epicpeople.org/ethnography-and-music-disseminating-ethnographic-research-inside-organizations/

Bateson, Nora. 2023. Combining. S.I.: Triarchy Press.

Buchanan, Richard. 1992. “Wicked Problems in Design Thinking.” Design Issues 8 (2): 5. https://doi.org/10.2307/1511637.

Bueno, Carmen Patricia, Consuelo González, Lucía Laurent-Neva, Maximino Matus, Nora Morales, and Ivonne Ramírez. 2023. “Lessons from the 4th Global Business Anthropology Summit.” Journal of Business Anthropology 12 (2): 238–71. https://doi.org/10.22439/jba.v12i2.7063.

Di Paolo, Ezequiel A. 2021. “Enactive Becoming.” Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 20 (5): 783–809. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-019-09654-1.

Di Paolo, Ezequiel, and Hanne De Jaegher. 2012. “The Interactive Brain Hypothesis.” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2012.00163.

Di Paolo, Ezequiel A., and Hanne De Jaegher. 2022. “Enactive Ethics: Difference Becoming Participation.” Topoi 41 (2): 241–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-021-09766-x.

Hayashi, Arawana, and Otto Scharmer. 2021. Social Presencing Theater: The Art of Making a True Move. Cambridge, MA: PI Press (Presencing Institute).

Littlewood, William C., and Mary Alice Roche. 2004. Waking Up: The Work of Charlotte Selver. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse.

Roberts, Simon, and Tom Hoy. 2015. “Knowing That and Knowing How: Towards Embodied Strategy.” Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings ISSN 1559-8918. https://www.epicpeople.org/knowing-that-and-knowing-how-towards-embodied-strategy/

Rosa, Hartmut. 2019. Resonance: A Sociology of the Relationship to the World. Medford, MA: Polity Press.

Scarano, Fabio Rubio. 2024. Regenerative Dialogues for Sustainable Futures: Integrating Science, Arts, Spirituality, and Ancestral Knowledge for Planetary Wellbeing. Sustainable Development Goals Series. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-51841-6.

Scharmer, Claus Otto. 2018. The Essentials of Theory U: Core Principles and Applications. First edition. Oakland, CA: BK Berrett-Koehler Publishers Inc.

Scharmer, Claus Otto. 2016. Theory U: Leading from the Future as It Emerges. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Sepúlveda-Pedro, Miguel A. 2024. “Sense-Making in the Wild: The Historical and Ecological Depth of Enactive Processes of Life and Cognition.” Adaptive Behavior 32 (2): 117–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/10597123231190153.

Shove, Elizabeth, Mika Pantzar, and Matt Watson. 2012. The Dynamics of Social Practice: Everyday Life and How It Changes. 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road, London, EC1Y 1SP, United Kingdom: SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446250655.