“Innovate or die”—this dictum is driving companies to build their innovation capacity, and fast. Most are turning to now-familiar practices such as Design Thinking, Lean, or Agile. But as they grow, many organizations find that they don’t see expected increases in innovation after deploying these practices. Why?

Although they’re originally meant to drive creative thinking and strategic risk taking, innovation methods can quickly become rote in large organizations, especially when teams are expected to deploy them without context, or simply to check off a box on their performance reviews. Worse yet, some companies struggle to manage a combination of different innovation practices between teams, leading to a breakdown in collaboration and disjointed project pacing. What these organizations lack is an overall innovation strategy that drives their efforts to build innovation capacity, engages their teams with a purposeful vision, and ensures their efforts can evolve to meet changing conditions and business challenges.

Ethnographic thinking is a powerful approach that organizations and innovation teams can use to strategically guide how they innovate. Ethnography has grown in popularity as a research method, but as I’ve argued, it is more than just a tool. Ethnographic thinking operates at a strategic level,

“asking not just what consumers want, but why the organization is solving for that particular challenge in the first place…. Just as importantly, contemporary ethnographic thinking turns the gaze back on itself, forcing organizations and practitioners to come to terms with their own histories and orthodoxies, and to face how those realistically impact their capacity, or inclination, to innovate.”

But how exactly can companies and teams ‘operationalize’ ethnographic thinking in tangible ways? Building an innovation strategy—framed in cultural terms—is one answer to that question. This story from my book Ethnographic Thinking offers one example of what it can look like.

An Existential Crisis

I stood in a former factory converted to open-concept work lofts. All around me were the trappings of a highly productive innovation team: stacks of foam core boards loaded with Post-Its, baskets full of external hard drives, rolling white boards with “do not erase” scrawled across the top, a wide variety of dart boards and Nerf toys, Sharpies and markers of every color, and an odd collection of stuffed animals propped up on one of the huge wooden beams that spanned the room’s brick walls.

My client said something like this:

“We’ve been conducting research, developing great insights, and generating outstanding ideas over that past five years, but we don’t have any real way to make sense of it all. Sometimes it feels like we’re chasing one trend after another.”

So I asked, “If you did have a way of making sense of all your work, what benefits do you imagine that would bring?” The answer was a variation of one I’ve heard again and again:

“We know so much about our customers, our sales force, our competition…even our indirect competitors. If we had a way to organize and channel this knowledge, we could have more influence within the company, drive more change internally, and improve profits with the new business models and other innovations our team develops.”

Ultimately, I told this client, it’s about finding your strategic value. This means going beyond displaying your strengths in human-centered design, research methods, and iterative prototyping. It means developing systems thinking, including a longitudinal understanding of your insights, and a clear view of your company’s internal culture (as well as your role within it). It also includes positioning those learnings within industry developments, stakeholder cultures, and broader emerging cultural phenomena.

Here is the process we used to develop an innovation strategy to give the team greater focus and help them prioritize and optimize their work for increased impact.

Phase I: Using a Longitudinal Lens to Demonstrate Strategic Value

The team had over five years of data, themes, and insights from a wide range of projects and sources. We tackled this bounty in two stages.

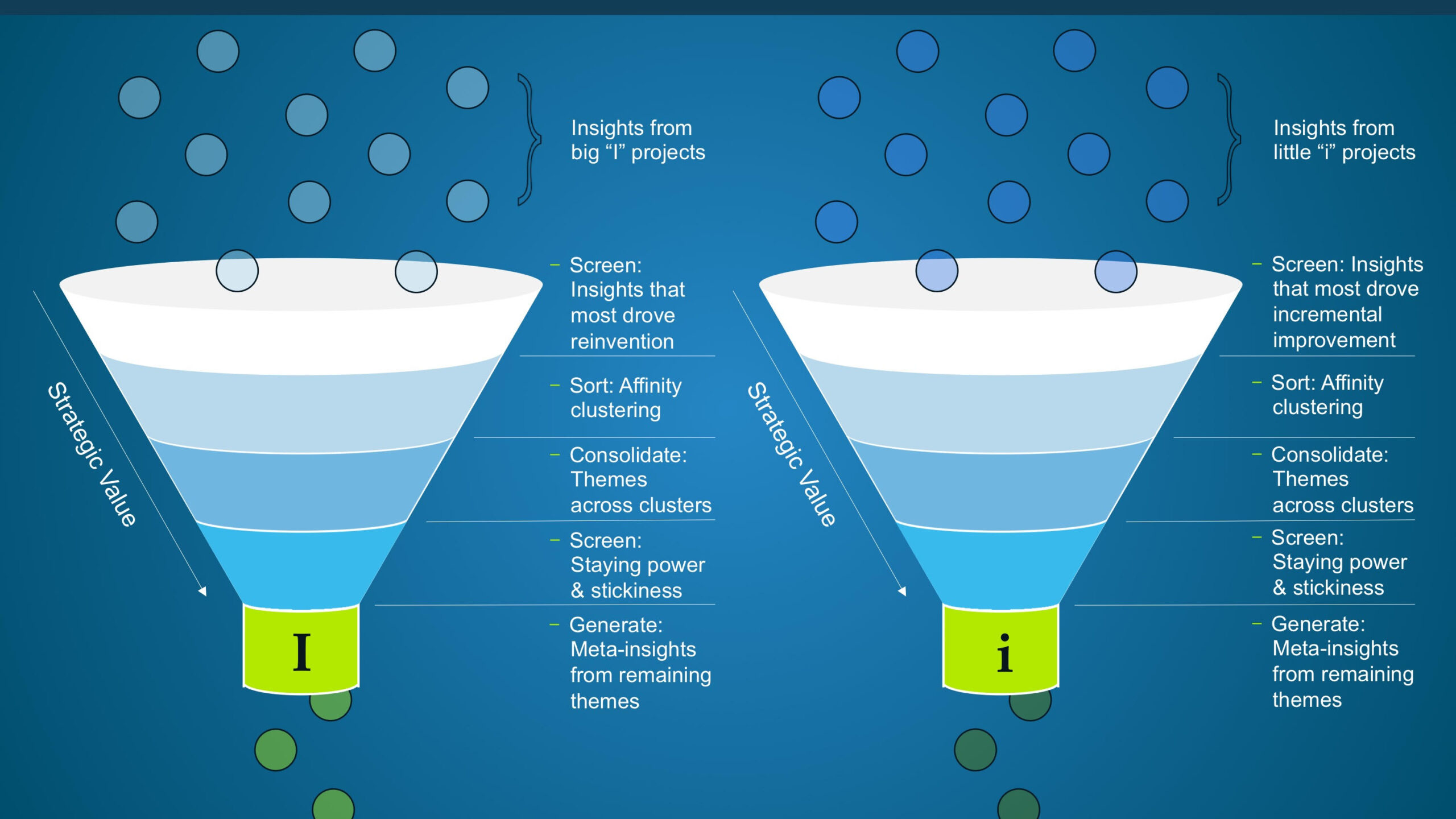

First, we classified projects as either “big I” innovation—focused on developing entirely new human-centered models, products, services, or systems—or “small i” innovation—smaller scale and focused on incremental improvements to the company’s current offerings.

Then we synthesized insights across all projects in each of these two categories to identify recurring longitudinal themes. For “big I” projects we asked: “which insights consistently drove projects that successfully reinvented, or had high potential to reinvent, the company’s offerings in significant ways?” For “little i” projects we asked, “which insights were most useful in consistently improving some portion of the company’s offering?” Together, these became our MVP insights, which we clustered to identify overarching themes. Themes with the greatest “staying power” or “stickiness” over time and across projects were used to create a set of ‘meta-insights.’

This process delivered four key benefits to the team:

- a longitudinal lens for understanding and communicating the ongoing strategic value of their work;

- a means of identifying patterns of scope and scale that were most valuable for the success of big I versus little i projects (particularly useful for budgeting);

- a new understanding of insights that were screened out, but were significant outliers, and how they might serve as early indicators for new directions to explore as yet unrealized opportunities for the company;

- a set of overarching ‘meta-insights’ that could be used to frame the purpose and position of the team within the company, and the industry more broadly.

Our second step in this phase was to identify the set of insights that were most useful for fulfilling specific strategic goals for the company. We sorted the team’s projects according to the main purpose each served within the company’s strategic directions: expanding market share in a declining or static market, improving efficiency, reaching new demographics, revising sales models, and so on.

From there we synthesized insights that addressed each purpose. The results of this analysis succinctly demonstrated the team’s strategic value within the company, including how the team’s work filled the gap between the company’s strategic goals and customer needs. This analysis also delivered tailored sets of insights that other teams in the company could use to drive their own customer-centered work.

Results from both analyses—developing meta-insights and identifying their strategic value—empowered the innovation team to prioritize and manage their projects more effectively and strategically. For example, the team was approached to lead a project to expand market share for a company subsidiary. They were able to work with others in the company to strategically refine the project structure and scope in ways that built on previous insights. This included:

- determining whether or not the proposed project was aligned with (or showed promise to productively disrupt) the team’s meta-insights to determine its potential to build on the team’s previous work and leverage its value;

- looking back at similar projects to classify the potential project as “big I” or “little i” to accurately set budget and resources;

- capturing the most effective and relevant longitudinal insights from similar projects to help frame and focus their project structure and lines of inquiry more effectively; and,

- re-visiting insights from projects that fell under the same strategic direction or initiative to map out where insights from this new project were most likely to make an impact within the company.

Together, these steps allowed the team to build a well-informed and more streamlined project plan with better prospects for actionable outcomes that were aligned with the company’s strategy.

In this approach, many ethnographers will recognize at least some of their own processes for making sense of the widely varying forms of data they collect—interview transcripts, photographs, audio recordings, artifacts, field notes, secondary research, and other sources. We regularly sort out the significance and relevance of overwhelming sets of data from disparate sources to form well-substantiated interpretations and build valuable insights. And ethnographers often shift focus between broad overviews and deep dives, apply different lenses to the same bodies of data, and map relationships between different sets of data to identify alignments, interdependencies, disruptions, and other dynamics at play.

We applied these same ethnographic patterns of thinking to the challenge of making sense of the team’s data over time, across many projects, and with respect to organizational strategy.

Phase 2: A Broader Look

Our work in phase one established a strategic foundation, but it didn’t completely fulfill the goals of an innovation strategy rooted in cultural terms. We still needed context from other key cultural domains, including a deep understanding of the company’s internal culture, stakeholder cultures, and analogous cultures.

So, in phase two we broadened our perspective to understand each of these domains in relationship to customer cultures and how they could be leveraged. This took our innovation strategy to a higher level, empowering the team to demonstrate broader relevance, build momentum from other cultural domains, and delineate clear pathways for action.

Looking in

We began with the company’s internal culture, systematically studying the daily lives and practices of employees from as many different departments and levels of seniority as possible. Through interviews, observations, participatory observation, and shadowing, we examined their norms, values, beliefs, history, informal networks, routine practices, unchallenged orthodoxies, and reward structures.

With insights from our analysis, the team was able to:

- identify existing pathways and practices within the company that were most compatible with the team’s work;

- better integrate their insights within the various workflows of colleagues on other teams to build mutually beneficial relationships and increase the odds of long-term support for their work; and

- determine which company values aligned best with customer values so that the team’s work could serve as a bridge for building and improving customer-centered initiatives (or identifying opportunities for change within the company in cases of misalignment).

Looking around

Of course, both customer and company cultures are continually influenced by many different forces. In order to drive truly innovative change, the team needed to expand its framework to optimize for broader cultural relevance and deeper impact. So in addition to “looking out” at customer needs and “looking in” at company culture, it was critical to “look around” at stakeholder cultures that influenced them.

For example, the team investigated online gurus and bloggers as key stakeholders, asking questions such as: How do they define discourses around the company’s offerings and the industry more broadly? How do their opinions influence the relationship between customer and company? What degree of influence do these and other stakeholders have over customer behaviors? How do they shape their priorities? Their values? Their aesthetic choices? How do they set the boundaries and propel the trajectories of customer interests? What motivates stakeholders to act in ways that impact customers? What cultural traits do they share with customers? With the company culture? How do they differ?

Using both primary and secondary research, the team synthesized a set of basic insights focused on stakeholders. Pairing this with results from scenario planning and quantitative work from the company’s strategy and marketing departments helped them sort out the relative weight, scale, and some potential future trajectories of their own insights.

Collectively, stakeholder insights were critical to gain a full understanding of the flows and spheres of influence that set the context for much of the team’s work as their ideas were developed, prototyped, tested, and eventually found their way into the marketplace. Frameworks such as flow diagrams, experience blueprints, and other approaches were critical for helping the team see and communicate the value of understanding the impact of stakeholders on both the company’s current offerings and those in the innovation pipeline.

In terms of ethnographic thinking, our “looking around” work provided the same kind of contextual awareness that ethnographers find essential for developing full understandings of cultures and human interactions within them.

Looking adjacent

Next, the team needed to “look adjacent” by integrating insights from analogous cultures, movements, or practices that could be used to inspire new thinking and point toward parallel trends that could impact the company in one form or another. This ensured that they weren’t constraining their thinking too much by limiting their ideas to what was traditionally “possible” in their industry, or allowing the orthodoxies and historical biases of the company’s culture to over-shadow the range of ideas they considered.

Luckily, analogous research had been built into most of their “big I” projects. For example, while conducting research to improve their sales model for younger sales representatives, they studied early entrepreneurship well outside of their industry, including a young man building a hip hop brand around t-shirts and skate culture; a budding jewelry saleswoman operating out of a cart in Central Park; and many others. They also explored parallel and competing business models, and again incorporated secondary sources such as competitive intelligence and industry landscape data.

The team clustered insights from their research on analogous cultures and evaluated them for their potential to help them expand beyond the traditional scope of their work and inspire creative ideation within the context of the company’s core values. They then compared those results to insights from customer, company, and stakeholder cultures to highlight relationships between them, point toward larger, overarching cultural trends (e.g., the changing nature of work), and investigate how analogous insights had the potential to impact the company’s offerings.

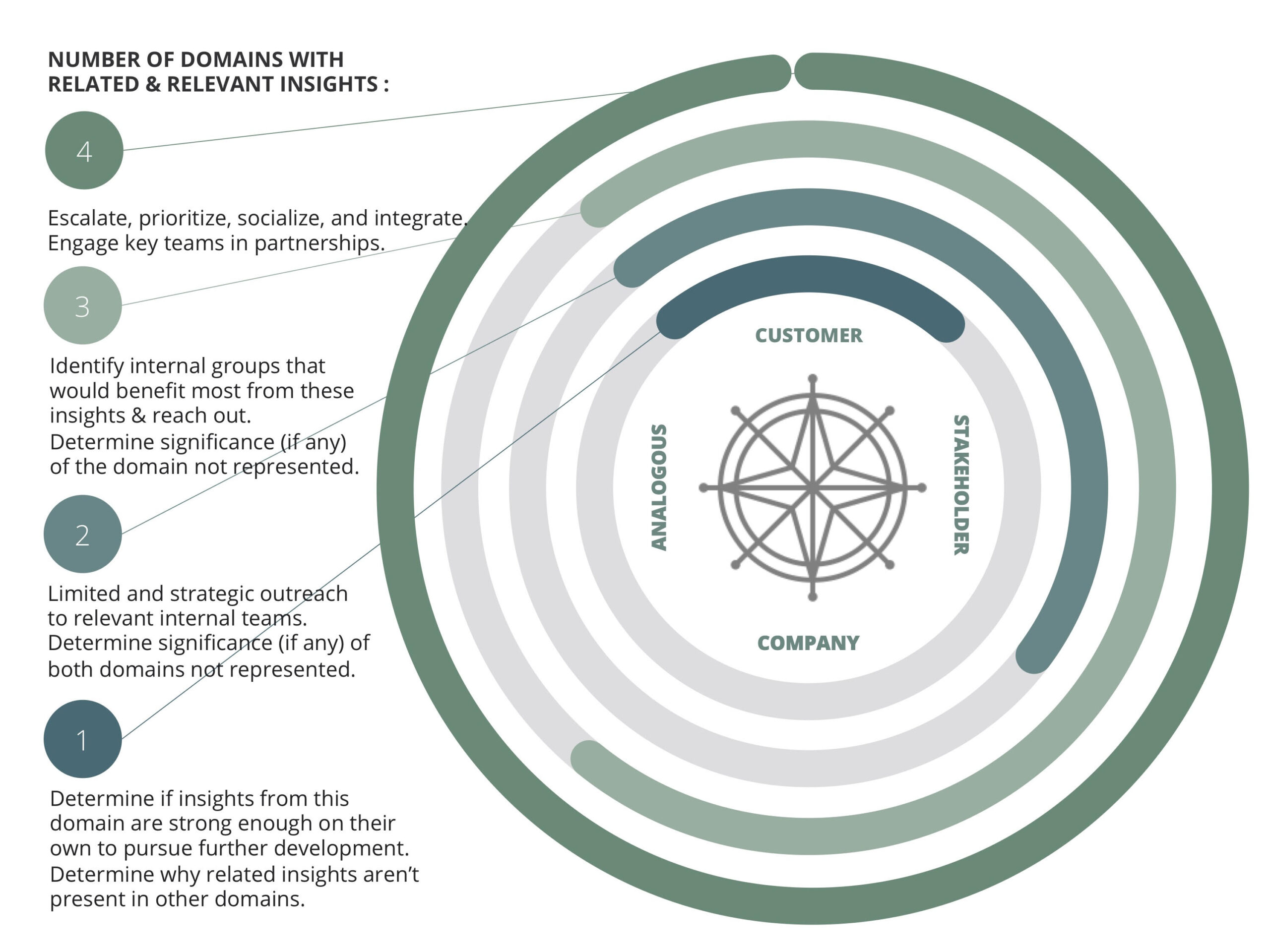

A Guiding Force: “The Compass”

One critical way ethnographers generate deep insights is through cross-cultural comparisons. Likewise, by comparing, contrasting, and integrating insights from company, stakeholder, and analogous cultures, we developed an innovation strategy for this team that went beyond chasing trends. They could now point to long-term cultural phenomena across different cultural domains to demonstrate relevant, robust interactions and interdependencies. This allowed them to position, prioritize, and channel projects to increase their influence and strategic impact by pointing to well-substantiated momentum across multiple cultural domains. It also provided them with the comparative data to highlight significant anomalies within a particular cultural domain that could serve as early indicators of industry disruption.

Collectively, these comparisons provided what might be called ‘directional’ value. In fact, the master framework for the team’s innovation strategy was eventually dubbed The Compass to reflect how it was used—not only within the innovation team, but more broadly to strategically influence initiatives within the company.

In one example, the team’s analogous research revealed a consistent rise in the popularity of online selling that they believed competed with the company’s primary business model. The company never identified as “a technology company,” so online selling—and the digital domain generally—wasn’t seen as relevant to its business model. But now, the team could use The Compass to make a powerful argument for innovation in this space. They pointed to field observations and insights about online selling from analogous domains, their own customer research, and stakeholder cultures. This demonstrated alignment in three different ‘directions’ of The Compass, which provided them with a key tool to identify a gap in the company culture domain and argue for a strategic adjustment in its operations and offerings to compete with online sales platforms.

In the end, creating The Compass helped the team demonstrate that innovation is about more than processes, Post-Its, and brainstorms. Fundamentally, it’s about understanding cultures. Getting from field to insights to prototype to marketplace requires the ability to understand consumer, company, stakeholder, and analogous cultures and how they interact. By applying ethnographic thinking to this constellation of domains, the team provided insights that went far beyond identifying customer needs. They were able to demonstrate and substantiate the broader cultural bases for bringing new ideas to market with greater cultural alignment and reduced risk for the company.

Image: S11 by maxonerock (CC BY-NC 2.0) via flickr.

Related

Beyond the Toolbox: What Ethnographic Thinking Can Offer in a Shifting Marketplace, Jay Hasbrouck

Meaningful Innovation: Ethnographic Potential in the Startup and Venture Capital Spheres, Julia Haines

Five Steps Behind: How Ethnography Based Strategy Can Fuel Ingredient Innovation in the Early Stages of the Value Chain, Martin Millard & Yosha Gargeya

0 Comments