Public sector innovation (PSI) is an emerging multidisciplinary field that is attracting practitioners from a wide range of sectors and industries, with a correspondingly broad set of skills and experience. PSI aims to significantly improve the services that a government has the responsibility to provide by taking a user-centered, partnership-based approach, from service content development through to methods of service provision (OECD 2012). Yet the work is complex and not without risk, if undertaken without appropriate foresight, thoughtfulness, and rigor. In particular, when it comes to pursuing PSI in the design of social service policy and its provision, some of the more substantial risks lie hidden in systemic power imbalances that can easily be exacerbated, despite practitioners’ best intentions. This article uses a case study about homeless service provision in New York City (NYC) to offer a candid portrayal of undertaking research and design work in PSI. It highlights common challenges and risks, as well as best practices for mitigating them. The issue of power is examined through the lens of agency, as it’s a productive framework for helping to identify and work with the power dynamics that circulate between everyone involved in PSI design projects: the project team, research and design participants, intended end users, and the government client. In the spirit of making a pragmatic contribution to a burgeoning field, this article ultimately advocates for a reflexive practice. Working reflexively means inhabiting a mindset of self-awareness, reflection, and never ‘turning off’ as a researcher. This reflexivity enables practitioners to navigate the complexities of PSI design work, and ultimately, to better support their government agency client and those that the agency is aiming to serve.

INTRODUCTION

“Some people have been here for years. I can never see myself raising my child in this shelter… I have to focus on the task here and get out” (Resident).

She’s buoyant, dressed in scrubs, smiling as she begins to talk. She describes arriving at the shelter with her young daughter and boyfriend; his departure not long later; juggling work, education, and childcare; her panic attacks; trying to be a good mother; wandering the local grocery store until the 9 p.m. shelter curfew because anything is better than “being inside”. But the nine-month merry-go-round of case management meetings, apartment viewings and discriminatory knockbacks is over. She and her daughter have a home to go to.

This interview is just one of fifty-two that the Public Policy Lab (PPL) collected as a part of Navigating Home, a project completed with a New York City (NYC) social services agency. The project focused on understanding how the government agency and nonprofit organizations that run the city’s homeless shelters can better assist residents in transitioning to permanent housing. The scale of this challenge is significant. At the time of writing this article in August 2019, approximately 61,674 New Yorkers were being housed in homeless shelters, including 14,806 families, and 21,802 children (Coalition for the Homeless 2019).

Project Context

Navigating Home aimed to understand why the task of assisting NYC shelter residents in finding permanent housing is executed with varying degrees of success across the general population homeless shelter network. The project’s focus was two-fold: understanding what makes some shelters ‘positive deviants’ (Pascale, Sternin, Sternin 2010) that consistently meet their move out targets; and understanding how housing specialists – a shelter staff member who assists residents in navigating NYC’s housing market, understanding subsidies, and applying for housing – might be best leveraged to impact move-out rates.

PPL was enlisted to design and test interventions – such as tools, materials, and processes – that would support both frontline staff and residents in the effort of gaining and maintaining permanent housing. As a non-profit public sector innovation (PSI) lab that partners with government agencies to address challenges faced by low-income and at-risk Americans, PPL combines systems thinking and human-centered research, design, and evaluation methods. PSI is a growing field that aims to innovate public sector service provision through partnership-focused and user-centered practices. The PPL approach to policy and service delivery redesign reflects emerging practices in PSI. As a design firm that positions itself as an operational and strategic partner to government, PPL’s practices are both strategic and material, focusing on system interventions that seek multi-level impact. These include policy changes through to behavior change compelled by new or improved interactions between people, as supported by digital and physical tools. From this perspective, Navigating Home was focused towards producing a ‘proof of concept’: identifying and validating areas of intervention that could improve move-out rates. In order to test the validity of these interventions, PPL collaborated with government partners, shelter staff, and residents to design and test a set of service concepts and related prototypes. The five-month project (December 2018 – April 2019) comprised 250 hours of field research and co-design with 215 shelter staff and residents across twelve shelters in NYC. This Phase One proof-of-concept work laid the foundation for Phase Two, in which program models and tools are being further developed and tested, leading to small-scale pilots.

A Cautionary Note

A project such as this requires thoughtfulness and caution. With so many interdependent variables at play, practitioners must be mindful of the systems they’re designing within and for. Broadly, these risks relate to power and potential unintended consequences of perpetuating unjust dynamics that already limit shelter residents’ ability to seek and maintain housing, as well as frontline staff’s ability to serve them. It is worth noting that this concern extends well beyond Navigating Home, as every social service plays a hand in perpetuating dynamics of power and agency. PSI practitioners need to be highly sensitive to these dynamics, asking: where is power in excess? Where is agency lacking but assumed, meaning that expectations can never be met as people aren’t being empowered to do what’s required or in their best interest? In addition, when considering the circulation of power and agency from a systems perspective, these questions need to be asked not just about the people being served, but also of the government agency client and the project team themselves. As one of PPL’s directors noted, “one of the things we have to do in our work, as mediators between large government systems and individual humans, is to manage power dynamics. We have to mitigate our own power – our own increased power over members of the community, and then we need to turn around and carry those stories into rooms of people who have more power than we do – in and over public systems” (2019).

If these power dynamics are not explicitly addressed and mitigated as a part of design practice, very significant risks relating to the unintended consequences may emerge, given that the service users are often at-risk and in vulnerable, disempowering circumstances. As Paola Pierri argues, “The question of agency is one that cannot be given for granted or ignored, especially when design practitioners are involved in societal issues where dynamics of exclusion and self-exclusion are at play, which can prevent people to act in their own interest…” (2017, S2956–S2957). Therefore, when designing for the social sector, designers must be cognizant of the complex systems that can either impede or aid an individual’s expression of agency.

This article therefore surveys what PPL learned during Navigating Home in terms of working with agency as PSI research and design practitioners and defining a methodology which was sensitive to its dynamics. Rather than presenting a blow-by-blow of each project phase and its outcomes, this article focuses on four areas that were most critical for team reflection and practice development when undertaking the project. These include:

- Research planning that aims to mitigate likely power imbalances between the project team and their participants;

- Data analysis frameworks that help identify unique systemic complexities relating to agency, and a process of data synthesis that enables prioritization of areas for design intervention;

- Co-design practices that both redistribute power between the team and participants and result in effective prototypes; and

- A client engagement approach that positions them as partners so as to become advocates for the project.

The article comes to a close with final reflections about Navigating Home and the subsequent proposal that PSI design work requires a ‘reflexive practice’. This is a project approach that demands self-awareness in light of the literacy required to negotiate power and agency.

While aiming to describe best practices, this article also intends to share a candid portrayal of the challenges associated with doing work of this kind. It does so to explicitly address the dearth of realistic appraisals of service design work, particularly around issues of power. As Yoko Akama (2009) and others (Blomkamp 2018; Kimbell and Seidel 2008; Pierri 2017) have noted, service design-related case studies often lack critical reflection, in part due to non-disclosure agreements or a reluctance to air challenges that may dampen emerging interest in a new field. The outcome of authors offering only a starry-eyed view of their discipline is that newer practitioners and future clients do not understand how difficult and complex this work is, nor learn about risks and how they can be mitigated, as Pierri emphasizes: “serious analysis of agency and power are long overdue alongside more optimistic accounts of collaborative design projects, which are seen most of the time as ethical and good in their own right” (2017, S2952). This article has therefore been written for readers who may be: working in the social sector and service delivery; exploring issues of reflexivity and power in their work; interested in systems thinking and human-centered design; working with vulnerable populations; or looking to shift from commercial to social sector design work.

REDISTRIBUTING POWER THROUGH PLANNING AND FIELDWORK

One difficult reality of undertaking human-centered design in the social sector is navigating the power asymmetries that influence relationship dynamics between a project team and their participants. Imbalances are usually perpetuated by privileges relating to increased social capital and mobility, as well as the team’s positioning as consultants who are empowered to hold space during fieldwork and make decisions that may directly or indirectly affect participants’ lives. Unconscious biases (on the part of both participants and team members) may also reinforce this asymmetry. These seemingly entrenched dynamics raise a question as to how a project team can manage its likely excessive agency during fieldwork, and mitigate its impact on both participants and the project outcome.

The management of power imbalances requires sensitivity, but also tactical pragmatism. While it’s beyond most designers’ ability to fully mitigate the various forms of systemic disempowerment that their participants are subject to, they can develop a protocol for redistributing power in the research environment. This starts with research planning that explicitly addresses power in terms of how it may be distributed unevenly and how this may impact data collection, project outcomes, and the well-being of everyone involved. It involves asking: in what ways might the team be wielding excessive agency? To what extent can a team cultivate a research environment in which participants feel at ease, safe, and free to engage with the project on their own terms? While similar concerns have long informed reflexive practices that have emerged in various social science disciplines (particularly anthropology), there is currently little guidance for designers working in PSI.

PPL addresses the challenge of power redistribution at two levels during planning. These are largely to do with its approach to data collection and management, as reflected in their sampling and consent practices. However, both of these presented with their own unique challenges when undertaken during Navigating Home.

Adaptive Sampling

A project team can attempt to redistribute power by making project-level considerations about whom data is being collected about – in short, an approach to sampling that seeks fair representation. Project outcomes can only ever be as good as the quality of data informing them, therefore if the sample skews incorrectly it’s likely the project will suffer a correspondingly imbalanced outcome. When considered in the context of public sector work, design informed by poor data can result in project outcomes that at best, fail to adequately support the people using the service, and at worst, harm them. Yet, the recruitment of shelter residents can be challenging.

Following previous project work with shelter residents, the PPL team anticipated that recruitment and certainly long-term project participation – as is often desirable in human-centred design (and an aspiration in PSI design work) – would be made difficult by the transience that permeates residents’ lives. Residents can be hard to pin down: they drop in and out of the shelter system, rotate through shelter intakes and assessments, or are moved to new shelters with little notice. Many avoid their shelter except to sleep, instead keeping busy with work or study and a life beyond its walls. Institutionalizing shelter routines – such as curfews – act as a daily anchor, yet there is little that would enable the design team to secure reliable participation. Frontline staff can be similarly difficult to recruit. Their schedules change around residents’ needs and unanticipated events at the shelter. There could be no complete assurance that the team could engage a consistent sample of frontline staff or residents and fulfil specific demographic, let alone psychographic, sampling requirements.

Unsurprisingly, once in the field these concerns were realized. Not only was scheduling a consistent sample challenging, but on occasion shelters were simply too busy to recruit effectively for the team, as one PPL team member described: “sometimes they would grab who was nearby… sometimes they forgot that we were coming… that meant that sometimes the residents didn’t have the agency or the context of participating” (2019). The team were dismayed to hear one very anxious couple relay that they had been told that they were meeting someone from a government agency, rather than the independent design consultants patiently awaiting them. In these instances, the consent process (explained in detail below) became an essential tool for rebalancing power and allowing the resident to determine whether they even wanted to participate.

To counter inconsistent recruitment the team doubled down on data triangulation. If an interview didn’t yield the anticipated data, the team could at least gather a specific, highly detailed set of field observations, tap into the subject matter expertise of government agency and frontline staff, and seek out additional secondary research. In addition, they sought to hasten data analysis and synthesis by undertaking it while still in the midst of fieldwork (in the Burger King across the street, in cabs, the subway, while hunched over lunch during hurried breaks). This acceleration enabled the team to rapidly develop early hypotheses that could be tested early on, rather than risk discovering data gaps once back in the office after fieldwork was complete.

Humanizing Data Collection

While all research and design participants should feel that the terms of their contribution to a project are transparent and within their control, this is especially important when the participants are homeless shelter residents. Institutionalized living regularly undermines feelings of independence and self-actualization, meaning that residents may be more sensitive to perceptions that their agency is being further eroded. PPL employs a research ethics protocol for data collection and management that aims to elicit and honor how each individual participant wishes to share their data. This protocol is grounded by principles of causing no harm, being honest, and being fair.

At one level, this plays out in the emotional dexterity it takes to create a supportive conversation environment: being sensitive to participants’ emotional safety while also being judiciously helpful, directing residents to resources as needed, although never giving advice. Power imbalances are also addressed through specific data gathering and storage protocols that aim to give residents control over their privacy, such as through the way that data is captured and stored. For example, the consent form is the only document on which the participant’s name is recorded. All other materials or files are labelled with a unique participant code and scrubbed of sensitive data. At the conclusion of each interview participants are also offered the opportunity to change, delete or retract comments, as well as review and delete any photos taken of them.

Conduct-informed data collection is perhaps most explicitly expressed through PPL’s informed consent process. While gaining participant consent is standard in academic research and recognized as best practice in most industry-based work, PSI project teams need to be even more sensitive to and transparent with their participants. For Navigating Home, the interview moderator talked through each aspect of the consent language in aid of participants with low English literacy or disabilities that impede reading or written completion of the form. This was also a crucial opportunity to build rapport and trust in a bureaucratic moment that could otherwise easily alienate a population already subject to repetitive, and at times frustrating, paperwork. Like most consent forms, the project and discussion aims were stated in simple language, including who the project was for, how data would be used, and any risks or benefits to the participant. Yet, in light of the circumstances participants were living in, researchers also needed to be careful not to stoke false hopes by expressing unclear aspirations about the project’s impact, particularly in relation to the participant’s own circumstances or case.

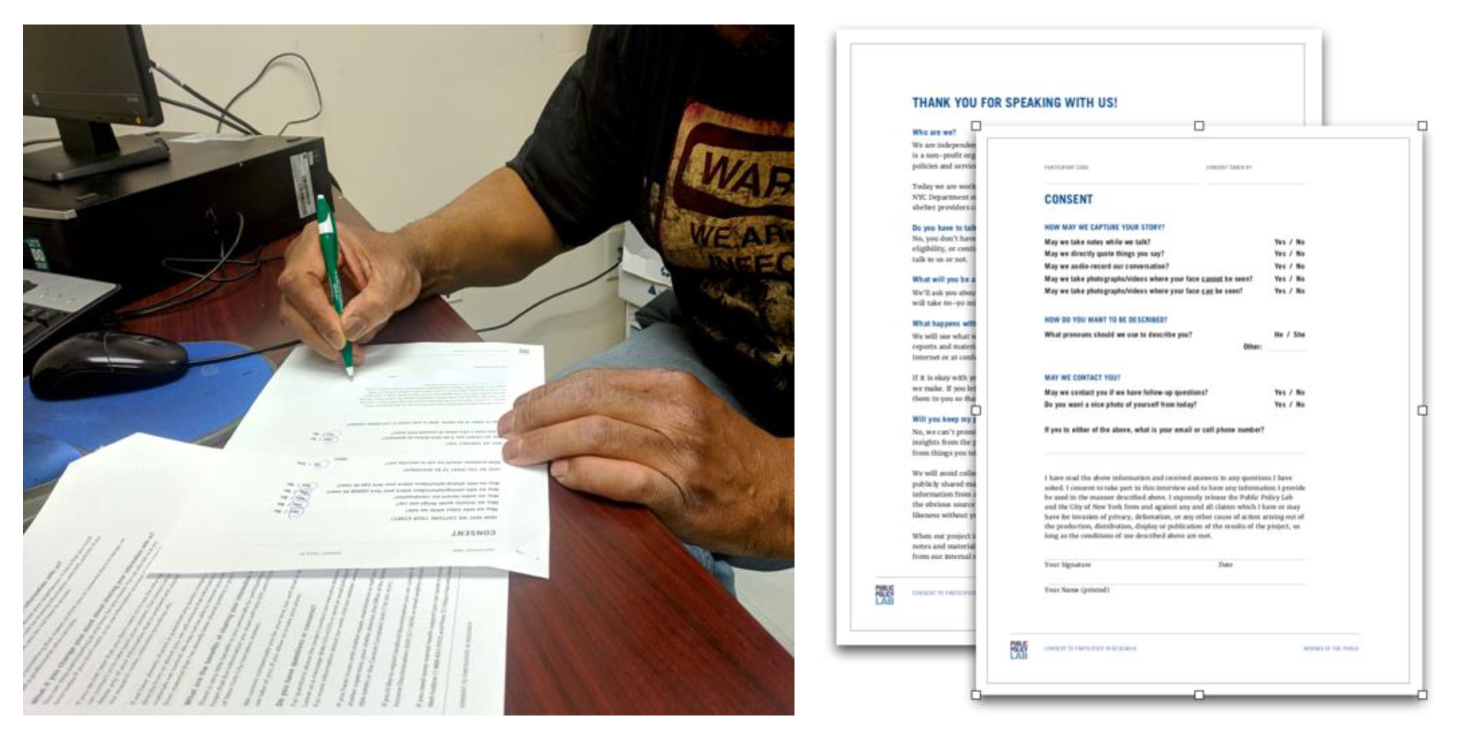

PPL also aspires to give their participants granular control over the type of data being collected about them. For example, the participant had the option to circle ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to each form of data, including notetaking, audio-recording, video-recording, pictures in which their face couldn’t be seen, and pictures in which their face could be seen (see Figure 1). In addition, the consent form offered a list of resources relating to discrimination, the reporting of shelter issues, and mental health, which the participant could keep. While most residents responded to the carefully laid consent process with some version of “I’ve got nothing to hide”, it wasn’t uncommon for the team to have stories of depression, trauma or prejudice shared with them. Without supportive resources on hand the team simply would not have been able to exercise adequate duty of care while out in the field.

Figure 1. PPL’s consent form. Photograph ©Public Policy Lab, used with permission.

The team also came to understand that consent wasn’t simply a moment of interaction during the interview process. In one instance, as the research session progressed the moderator observed that the participant did not appear to be well and that there was a good chance that he would not have been able to fully comprehend the conditions of participation. While feeling conflicted by the risk of acting paternalistically, the moderator ultimately cut the interview short and withdrew the participant’s data from the project.

Fieldwork: Understanding End Users and Systems

The team undertook its first round of shelter fieldwork over the course of three blisteringly cold, mid-winter weeks. They travelled the furthest reaches of NYC’s ailing subway system, visiting twelve shelters for about three hours each. They aimed to speak with two residents and two frontline staff (usually a housing specialist and a case manager) per shelter, as well as hold shorter conversations with operational leadership, such as the shelter or program director. In total they met with twenty-six frontline staff and eighteen residents. As fieldwork progressed, each shelter began to feel like its own laboratory – host to its own dynamics, practices, stories, and historical trajectory. Some were excellent partners, mines for learning and design ideas, and offering a strong spirit of cooperation and even transparency about the challenges they were facing. Others were less capable of partnership, often due to structural destabilization caused by a transition in leadership. In these circumstances the team could not breach their outsider status and had to contend with reading between the lines of the view they were being offered by the shelter.

Resident Research

Resident interviews comprised questions about the participant’s life story and how they came to be in the shelter, how they occupied their days, their perceptions about the type of support they were getting, followed by a short journey-mapping activity to chart the steps they had taken towards securing permanent housing, from shelter arrival through to the present day. This activity aimed to define key phases of a resident’s time in a shelter, document any service interactions, the associated successes or difficulties, and their ideas for improvement.

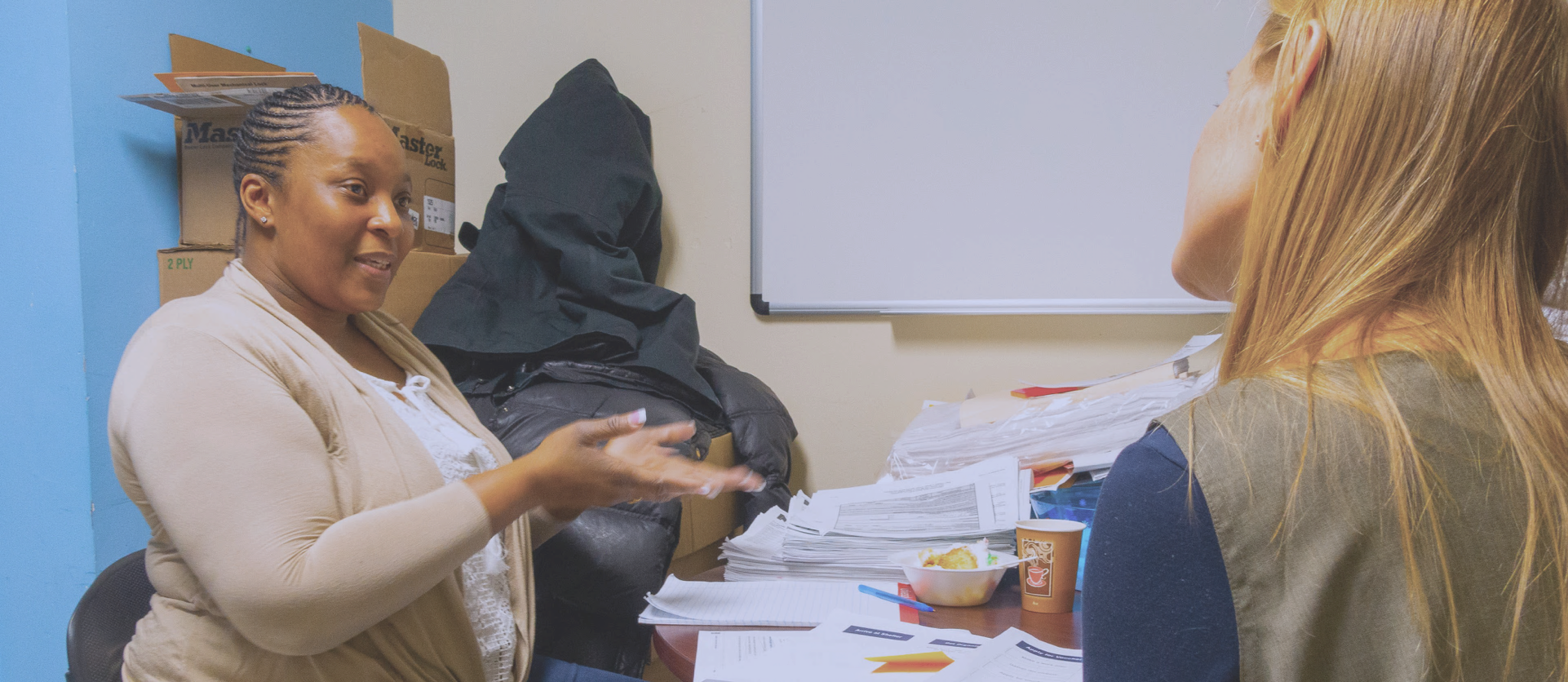

Figure 2: Shelter resident participating in fieldwork. Photograph © Public Policy Lab, used with permission.

Frontline Staff Research

Shelter staff interviews aimed to build a picture of how they approached their work (from personal motivation to responsibilities and activities), why some residents might be harder to support than others, as well as an overview of policies, training and systems. Staff participated in a journey mapping activity similar to that of the residents, however with a focus on capturing the tools, processes, and strategies used to support residents during their time in the shelter (see Figure 3). The team collected artifacts that staff were using to help residents (such as leaflets, websites), and especially those that they themselves had designed. Self-made tools can often be excellent seeds for design ideas as, in essence, these are prototypes that are already being tested.

Figure 3. A frontline staff member helping PPL map the rehousing journey. Photograph ©Public Policy Lab, used with permission.

System Immersions

To round out their fieldwork the team also sought better understanding of the technological systems that their prototypes could either leverage or integrate with. They participated in agency-organized ‘system immersion’ sessions to understand: data flow between agency operations and shelters, within shelters according to their own protocols and processes (such as assessments and case management meetings), within and between databases, and relating to frontline staff’s use of case management software. The team was also invited to cross-functional meetings in which they could speak with a range of program and operational agency staff responsible for shaping the policy decisions that influence how shelters are run, and through group discussions elicit the challenges that most concerned them, as well as ideas for addressing them. Finally, the team met with a team responsible for the case management system. Here the aim was to see how PPL’s recommendations could support or even guide the current development roadmap.

SYSTEMIC DATA ANALYSIS AND SYNTHESIS: IDENTIFYING INTERVENTION AREAS

“Sometimes when we talked to people about some of the challenges they’re facing I could identify the policy that took that safety-net away… increasing housing costs, gentrification, all of these systemic things… I would say that eighty percent of the folks that we spoke to were African-American. The communities are changing, people are getting pushed out of their homes, they’re dealing with housing discrimination, the cumulative impacts of [lack of] access to wealth and savings… The systemic barriers that people are facing… that is something I noticed when we were doing our fieldwork” (PPL Team Member).

With the core challenge of this project being to design service interventions that can realistically cultivate agency, data analysis would have to aid identification of moments in which the people who are due to be served by the project (in this instance, frontline staff and residents) could be truly empowered to act. There were two dimensions to identifying intervention areas. At one level, it involved conducting data analysis that differentiated between systemic barriers that were beyond the project’s scope and the factors that could actually be designed for – and that the team was best equipped to impact within the scope of their project. Methodologically, this involved a system-wide surveying of all of the challenges and needs that were captured during fieldwork, then determining the extent to which these were caused by large, structural factors that the team couldn’t directly impact, such as intergenerational poverty, economic conditions, or specific policies.

At another level, the team needed to determine whether all members of the target population could actually be designed for within the scope of the project. Here, data analysis was aided by use of a ‘mindset’ framework – a way to group participants’ attitudinal and behavioral patterns. Mindsets aim to encompass the dynamism of human experience, accounting for the fact that a mindset may change over the course of an hour, a day, or even a lifetime. Sometimes they’re triggered by a demographic variable like age, but more often they change with circumstances and events. Once a set of mindsets has been defined, additional validation during fieldwork helps to determine whether all mindsets should be designed for, or only a subset. Therefore, the outcome of data analysis and synthesis is a systemic mapping of how agency is expressed, denied, or supported; identification of specific areas for design intervention that can influence these dynamics; and a framework to guide the team in designing for true human needs and behaviors. These are described below.

Defining Systemic Barriers

For Navigating Home, given the team had been tasked with identifying the system-wide factors that differentiate high- and low-performing shelters, the first step involved surfacing all of the factors affecting shelter performance, then distinguishing those that were beyond the scope of the project to affect. Data from participant observation alone was highly suggestive, in that it seemed to differentiate between low- and high-performing shelters in very visceral ways.

For example, the experience of arriving at some shelters was telling, with stringent security measures casting a foreboding welcome and residents listlessly clustering around building entrances. These were generally people who were unable to or couldn’t find work. They told the team that they’d usually be out in the neighborhood, but the bitter cold was preventing them from venturing further afield. In these shelters, staff appeared to work autonomously and within well-worn hierarchies.

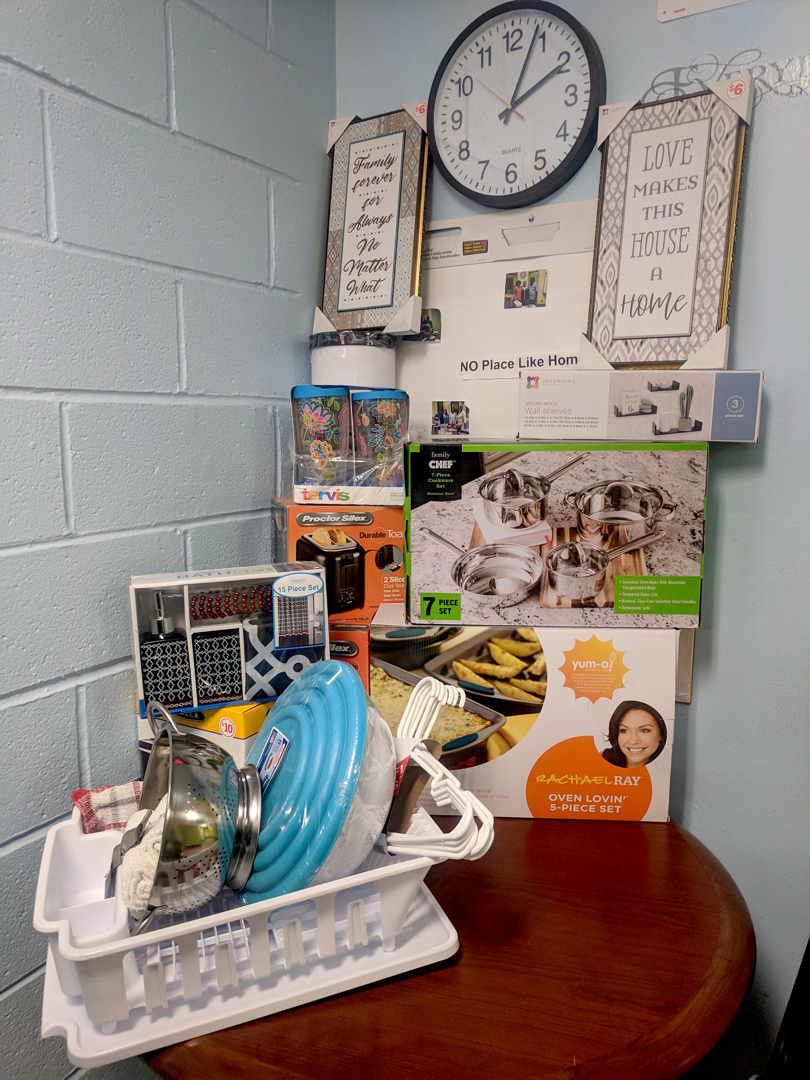

However, other shelters were bustling, warm, with residents and staff trading jokes and banter. In these shelters, walls heaved with community notices, as well as shelter and social service information. There were DIY efforts, such as ‘welcome kits’ (pots, pans, towels) on display that residents would receive upon departure to their new home (see Figure 4), and even staff-made posters that visualized the pathway to rehousing. Some had computer labs and well-publicized life- or career-skill workshops. There were also those that were actively partnering with local churches or community organizations to gather donations, such as books and clothing, or even to run programming. During one shelter visit, the team’s interview was interrupted by the clanging of an old-fashioned handbell. Staff and residents filled the nearby corridor with an excited, congratulatory buzz – someone had found a home, and it seemed that everyone was celebrating.

Figure 4. A ‘welcome kit’ on display at a shelter. Photograph ©Public Policy Lab, used with permission.

Yet regardless of shelter environment, there were factors that seemed to affect all shelters and impede residents’ ability to find housing. These included the lack of affordable housing in NYC’s notoriously tight rental market, clients with profound needs (usually mental and physical illness or substance abuse), as well as covert – and illegal – landlord discrimination, in which prospective tenants described being rejected without clear reasoning, but suspected factors such as their current housing status, race, and family make-up.

Identifying Intervention Areas

Given all shelters were grappling with the systemic constraints described above, when identifying opportunities for intervention, further analysis found that difference in shelter performance often lay in the culture of service provision – of leadership, of staff collaboration, of the way each staff member chooses to conduct themselves. These differences manifest in concrete terms through shelter processes and outcomes, such as how proactive each shelter’s programming was, how effectively staff shared knowledge and best practices, the quality of tools and materials that staff were using to help residents, and how supported residents felt.

For example, the function of housing specialists – an explicit project focus, as described earlier – became a litmus for understanding how service experience might vary between low- and high-performing shelters. In higher-performing shelters, housing specialists were often positioned within a well-integrated, cross-functional team. Most frontline staff were equipped with enough housing knowledge to field residents’ basic questions, and housing specialists were sensitive to case management needs beyond housing. Program directors regularly gathered frontline staff to triage difficult cases and collaboratively develop a strategy to help residents progress. There were also practices in place for knowledge- and skills-sharing, so that everyone could be kept in the loop with informal – but important – information that the case management program doesn’t capture (e.g. a sick child). By contrast, staff at lower-performing shelters tended to work in isolation, reactively, were not supported as effectively, nor did they seem to be supporting each other. When considering these observations in response to the project goal of better leveraging housing specialists, it became clear that Navigating Home would need to develop design concepts that encouraged well-integrated, proactive staffing environments.

The team synthesized their data by collating the staff and resident needs relating to service experience that they had documented, then grouped them into sets of ‘shared needs’. These are needs that are jointly shared by staff and residents and indicative of service gaps, which, in short, are opportunities for design intervention. This practice of designing for shared needs aims to make a larger systemic impact by encouraging joint behavior change, therefore resulting in a more salient service intervention as it encourages positive behavioural interdependency between staff and residents. These shared needs were reframed as ‘service factors’, which, when well-managed, corresponded to higher shelter performance – as is described briefly below.

Designing for Service Factors

Expertise

“There’s no training that can teach you what I’ve learned” (Frontline Staff).

Housing specialists often transition from real estate; however some do not realize that they require more than a well-thumbed Rolodex for their job. They also need an excellent working knowledge of agency services, to coach residents by using empathetic, trauma-informed ‘soft’ skills, and to exercise diplomacy in tough circumstances, such as landlord discrimination.

Relationships

“She has no leads… What’s being put on paper are lies… I don’t know if it’s because they don’t have anything but they should be honest with clients. Let us know they’re at a standstill” (Resident).

“We want them to know that we’re all working on the same goal” (Frontline Staff).

After years of feeling like they’ve fallen through the cracks, some residents are mistrustful of frontline staff. Without sincere engagement, they may not recognize the support available to them, nor feel motivated to fulfill their own obligations. Good relationships could be built through mutual expectation-setting, by cultivating informal rapport, and showing mutual respect.

Resident Management

“We don’t let anything slip, we address it head on… We meet the clients where they’re at” (Frontline Staff).

There are no ‘typical’ cases, but homeless services are largely predicated on a ‘one size fits all’ approach. If case manager assessments of residents could better evaluate each resident’s unique needs and intrinsic motivations, the service could be customized to meet residents where they’re at.

Timing

“I’m just trying to do the best that I can… And I don’t want the shelter to think that I’m not doing anything to get out of here. It’s not a bad place. It’s just not mine” (Resident).

Motivation to move out drains rapidly. New residents often arrive with an air of determination, but have unrealistic expectations about how long it will take to find housing. Inertia can be countered by setting clear expectations about the search process, and identifying intrinsic motivators that re-ignite dwindling momentum.

Goal-Setting

“[Residents] feel like no one is helping them and they lose hope after being in the system for a while”” (Frontline Staff).

Ideally, living in a shelter is just one period within a resident’s life. This time could be reframed as one of investment, rather than loss, as it could be utilized as an opportunity to build skills that could support independent living, such as budgeting, literacy, or self-care. Perceptions of consistent personal growth could also help build self-esteem and counter flagging motivation.

Information Channels

“Everyone gives you different information” (Resident).

While some information is in noisy abundance (plastering entire noticeboards, or strewn inconsistently around the web), there are significant gaps. Both staff and residents seek clear information about tools for navigating the journey to permanent housing.

Crafting Mindsets

Following synthesis of staff and resident needs, the team turned to defining resident mindsets according to the behavioral patterns and attitudinal tendencies they had documented. When considering how mindsets pertain to shelter move-out rates, it’s plausible that the extent to which residents are able to express the agency necessary to independently search for housing will depend on their mindset – a combination of attitudinal and behavioral factors. For many residents, for example, agency is diminished the longer they live in the shelter, as shelter life is both highly institutionalized and institutionalizing. Residents have little privacy, must eat when and what they’re told to eat, and must obey curfews or risk losing their bed. A proportion of residents have also already become enculturated to institutionalization for a better part of their lives, be it from living as children with homeless parents, spending time in institutionalized care, or for some, spending time incarcerated. Yet residing in an institutional environment wasn’t always viewed negatively, as it offered stability, relationships, and often much-needed support. However, institutional dependency could also heighten anxiety about the prospect of living independently. As one resident commented, “It’s a big transition. You get used to shelter life and when you’re out on your own, it’s depressing.”

In the context of people experiencing homelessness, the mindset framework recognizes that agency isn’t just something that needs to be made available to a shelter resident. Agency is something that’s expressed. It’s a practice that may require support depending on each individual’s circumstances. Yet it also takes into account the systemic barriers that might impede an individual’s ability to find housing, despite their sense of motivation or best efforts. These barriers relate to systemic factors described above, such as profound health needs. Some residents are able to progress proactively and are successful finding housing. Others are eager to move out but find that systemic challenges hold them back. And still others aren’t able to progress, but don’t seem to present with evident systemic barriers. This framework therefore makes it possible to scope design interventions that avoid perpetuating a ‘one size fits all’ approach, and avoid significant unintended consequences, as described by Donetto et al: “…the discourses of service user empowerment and democratization of service provision risk being deployed simplistically, thereby obfuscating more subtle forms of oppression and social exclusion” (2015, 242).

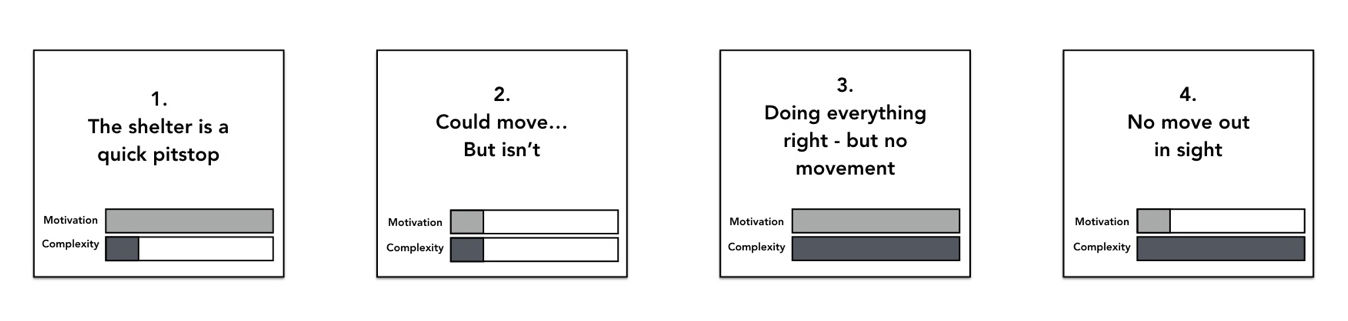

Following these observations, the team developed a matrix of four very broad resident mindsets that reflect two continua: the extent to which someone is intrinsically motivated and/or able to express agency, and the degree to which someone’s case complexity – the challenging systemic variables – impedes their ability to progress (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Resident mindsets used to explore the scope of potential design interventions. Graphic ©Public Policy Lab, used with permission.

While validating mindsets during fieldwork the team learned that Navigating Home would be most effective for two of the four mindsets. Frontline staff felt that the first mindset was typical of someone new to the shelter system, a circumstance in which motivation and ambition are plentiful, and needs to be swiftly leveraged while still abundant. They also proposed targeting the second mindset, as a vast proportion of residents were felt to fall into this group. Their needs, as opposed to those of the third and fourth mindsets, are not significantly profound, and therefore seemed good candidates for improved support. The final two mindsets reflect the experience of someone grappling with very profound needs and coming up against a range of systemic barriers. Designing for these mindsets would require more scope than was available to the team, given the sheer complexity of challenges, policy areas, and services supports that would need to be designed within. Overall then, while the project outcomes aimed to support all residents in some way, the design interventions were optimized to support residents falling into the first two mindsets.

CO-DESIGNING FOR POLITICS AND PRAGMATISM

The value of co-design in PSI can be thought of as two-fold. On one hand, it’s a pragmatic, design-led methodology for innovation that aims to generate new solutions by virtue of having engaged end users in the design process, as outcomes will more accurately address real needs and behaviors. On the other, there is an explicitly political aim. Given its roots in participatory design, co-design can aspire towards a similarly democratizing function. It can both empower participants during the process of co-design and result in artifacts that are empowering for end users (Blomkamp 2018). However, co-design is a practice that requires a sincere thoughtfulness and skilled facilitation. Designers must surrender the ‘expert-led’ mindset that is typical to design practice and instead enable participants to take up the reins as experts, so that their tacit knowledge can be surfaced and become a driver for design (Sanders 2008). In Navigating Home, co-design was especially challenging due to the trauma that pervades homelessness. Frontline staff confirmed that it would be likely that most residents would have experienced some level of trauma in their lives, and further, if to cast personal histories aside, living in a shelter in itself can be considered traumatizing. Frontline staff themselves had reflected on the toll of working in a traumatic environment. PPL’s co-design practice therefore needed to support a trauma-informed approach. This involved being particularly sensitive to their perceived power as design experts and by using tools that facilitated participant expertise.

Trauma-Informed Co-Design

While PPL’s team has had experience working with at-risk populations, and some members had previously worked with homeless participants, none of the team are trained social workers or therapists. Some team members felt this gap acutely while conducting research in the shelters, grappling with the emotional challenge of bearing witness to trauma while simultaneously navigating the discomfort of their own comparative privilege. In addition, some struggled with feelings of powerlessness as they watched evidence mount about the magnitude of the factors that underlie homelessness – poverty, intergenerational racism, inequity – the systemic factors that lay beyond the scope of the project. As one team member reflected, it was confronting to witness how significantly systemic barriers were impacting people’s lives while also realizing the limits of one’s own agency as a practitioner, and to proceed knowing that no single project could resolve those intractable challenges.

“Initially it was very challenging because you are trying to get particular types of information from people and they are sharing other pieces of information that they feel comfortable sharing, but you know you have no way to help. They’re not even asking you to help, but even just as a caring human being – hearing that is tough. It’s actually emotionally draining… I was physically tired…. I felt bad that my help was not impactful. How do you navigate these spaces?” (PPL Team Member).

In recognition of the realization that a responsible co-design practice would need to both support the well-being of participants as well as the team itself, PPL enlisted the support of a clinical psychologist specializing in trauma. He visited the office bi-monthly for the remainder of the project, something of an experiment for both the therapist and PPL. During debrief sessions he guided the team through the trauma they were witnessing, while also exploring their feelings of frustration and disempowerment in not being able to have a more immediate impact. The team was coached on creating a reassuring and safe environment through conversation cues, as well as interview closure practices, such as inviting residents to linger with the team after the interview, should they need time to settle before departing the privacy of the interview room. The sessions thus became an important space for pragmatic reflection outside the rush of project work, marking a new process of periodic reflexivity that enabled the team to develop a practice of exercising improved duty of care with residents, themselves, and each other. In the interest of deepening trauma-informed practices and honouring a space of reflection, the psychotherapist meetings have become a permanent and valued fixture at PPL.

There’s a thing about boundaries. It’s about the emotional capacity and maturity that it takes to be an individual representing an organization while looking at another individual who is living in some incredibly difficult circumstances. To be in that moment, to actually be compassionate, to actually care about the individual, but know that you can’t actually change that individual’s life… The work we do is hard. I think it’s pretty foolish for any one of us to think that we could engage with some kind of difficulty in people’s lives and complex systems without observing the trauma affecting us… If you are drawn to this work it is because you care about the world … But you’ve also made a strategic choice to do that at a systems level… and complicated feelings are going to come up with that (PPL Director 2019).

Outputs: Service Concepts

For the co-design phase the team returned to a selection of their original shelter sample, aiming for a tighter, more focused engagement with a smaller cohort of participants. Where possible they invited participation from their first participant sample, given that a trusted relationship had already been established. In total, they conducted co-design sessions with twenty-nine frontline staff and twenty-three residents. Putting trauma-informed co-design practices into play, these residents and staff members guided the team through the process of identifying prototype use cases, turning rough single-page sketches into journey maps and worksheets, parsing language into more relatable terms, and helping a visual language emerge (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. A frontline staff member participating in a co-design activity with PPL. Photograph ©Public Policy Lab, used with permission.

The team also took advantage of an opportunity to hold co-design sessions within the agency’s quarterly housing specialist trainings, which every one of NYC’s housing specialists was due to attend. They ran an activity that encouraged staff to design their ‘dream training’ with respect to content and format, and a mapping exercise to identify residents’ needs when moving into permanent housing (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Housing specialists participating in a co-design session with PPL. Photograph ©Public Policy Lab, used with permission.

The final outcomes of co-design were four service concepts spanning a range of intervention areas. The service concepts were validated through prototype-testing in which new tools, materials, and processes were designed with residents and staff, and that aim to encourage behaviour change in interactions between staff and residents, as well as support intrinsic motivation and informed decision-making. The four service concepts, along with the design objective guiding their direction, are described at a high level below.

Triage

“The Independent Living Plan is very client-focused but doesn’t include what case workers should do to help clients progress” (Frontline Staff).

Design objective: help frontline staff work proactively so that they can more easily meet clients where they’re at.

Research showed that residents currently endure lengthy and repetitive assessments that don’t always enable staff to make informed strategic decisions about the best path forward for their client. The team used the mindset framework to propose a tool that grouped residents into level of need, and to which a data-driven support pathway could be customized. This would enable residents to receive support tailored to their level of motivation, the complexity of their case (in light of the systemic challenges they were facing) and best option for rehousing, with optimized action steps for moving out.

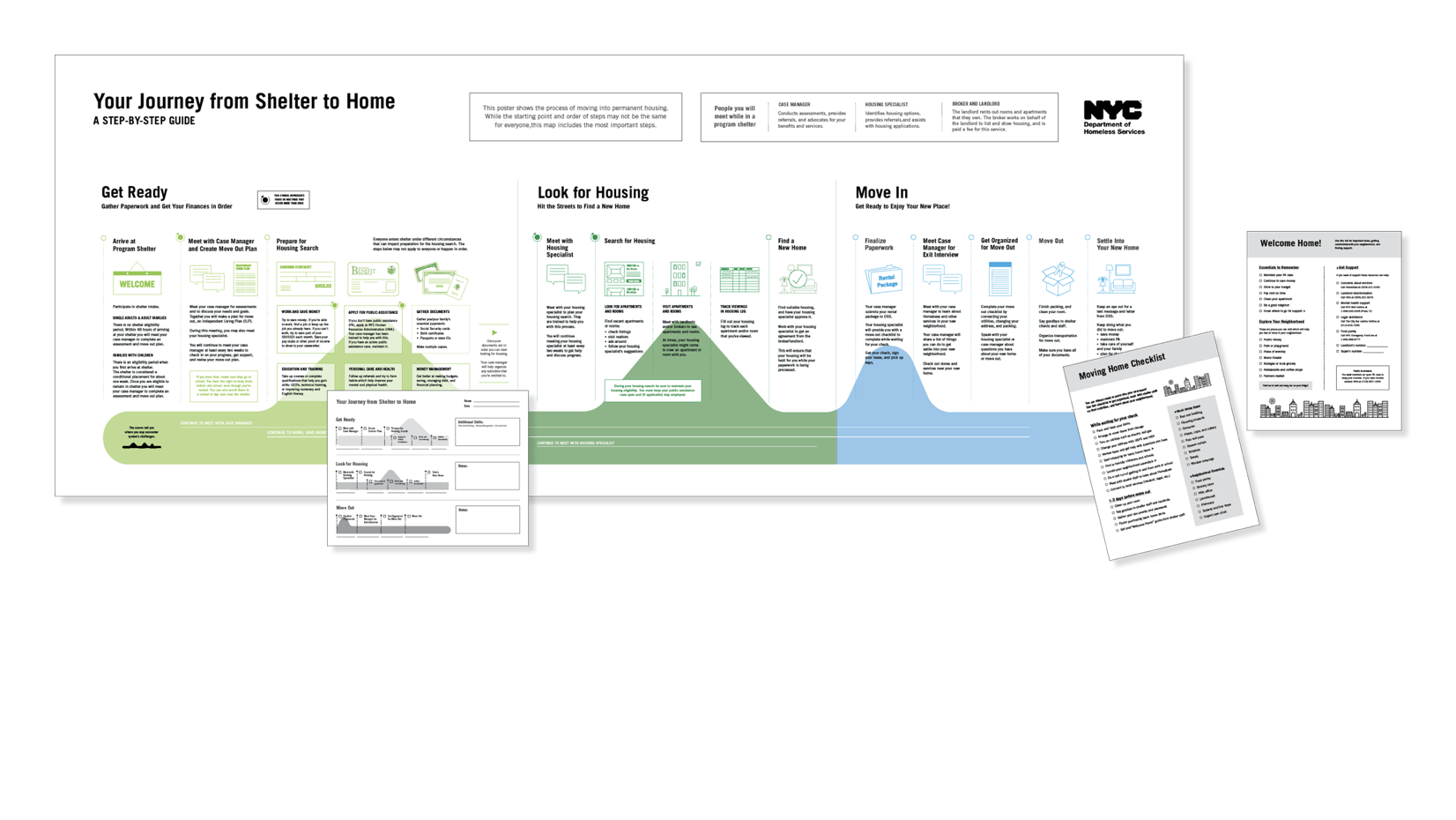

The Journey

“[The poster] would be so helpful because you really don’t know what is next. You know what people tell you… but you don’t have a clear picture of that” (Resident).

Design objective: provide motivating visual tools that make the journey intelligible to all stakeholders, build a spirit of collaboration, and enable everyone to undertake their responsibilities with greater ease.

Many residents don’t have a full picture of what lies ahead in their journey towards permanent housing. The future looms unknown, and with it a heightening anxiety. Besides some DIY attempts, staff lacked a reference tool to help explain the rehousing pathway. In response, the team designed a service poster that could be pinned up in common areas and frontline staff offices. They also designed an accompanying worksheet that could facilitate goal-setting discussions during case management meetings, as well as track progress along specific steps. It both reinforced the formal compliance activities that residents needed to undertake, while brokering an opportunity to set additional personal goals, such as completing educational qualifications. The team also proposed that the progress steps be tracked in the case management system, and that a reporting dashboard be built. By generating progress data and having the ability to export reports, frontline staff and shelter leadership would be able to make proactive, evidence-based decisions addressing client, staff, and shelter-wide needs, ideally as a part of a cross-functional case review workflow. The Journey proved to be one of the most popular concepts among shelter and government agency staff, as well as residents (see Figure 8).

Figure 8. A sample of journey prototypes. Graphic ©Public Policy Lab, used with permission.

Move Out

“It’s not just placing people in a unit. It’s about providing people advocacy and social service support once they’re placed” (Frontline Staff).

Design objective: create low-touch ways for frontline shelter staff to help residents transition into and maintain permanent housing.

As discussed earlier, the transition to independent living can be very daunting for those who have lived in institutions long-term. While the team couldn’t design an aftercare program within their project scope, they did develop a range of tools and processes that aimed to prepare residents for moving out, and make avenues of community support visible. These included a checklist that itemized all the steps a resident needed to undertake for a smooth move-out, from gathering personal documentation to purchasing household essentials. A ‘settling-in guide’ listed activities and resources that could lay the foundation for independent living, such as identifying the local supermarket, public transportation, health services, community amenities, and places of worship. These tools would be featured within a new exit protocol that case managers and residents could participate in – a meeting that focused on customizing support, connecting the resident to resources, and providing reassurance. PPL also proposed that, after moving out, the former-resident could receive periodic multi-channel follow up communications to remind them of the avenues of support available to them, as well as their rights.

Training

We are the tools for these clients (Frontline Staff).

Design objective: offer professional development for frontline staff that’s targeted, accessible, and impactful.

Both housing specialists and case managers were looking to grow their cross-functional expertise, as well as methods for more effectively motivating and empowering clients. In addition, housing specialists wanted to learn how to build their network of landlords and brokers and better communicate housing rights, while case managers wanted to better understand various public assistance rules. After surveying best practices and their fieldwork findings, the team recommended that trainings should be: practitioner-led so as to garner participant trust; reflect best practices in social service delivery by being grounded in trauma-informed, strength-based approaches; be delivered in multi-channel, interactive formats that can also be accessed asynchronously, with supportive materials that encouraged in-context use, such as meeting agendas, video clips, conversation guides, and tip sheets.

CLIENT ENGAGEMENT THAT EMPOWERS

The success of a PSI design project rests on more than the quality of deliverables. To make a truly robust impact, government agency partners must be both meaningfully engaged and strategically positioned, as described by Mieke Van der Bijl-Brouwer, “Innovation is not just about designing products and services – it is also about designing an organization or system that is able to disseminate solutions. Innovation takes design to a systems level” (2017, 188). Government agency partners need to feel like they have skin in the game, genuinely understand the project and its potential, and are being supported to become advocates for the project.

Participatory Partnership

When working with government agencies PPL aims to position itself as a facilitator and enabler. They take measures that encourage their clients and project stakeholders to take ownership of the project and become enthusiasts for its implementation. This approach is driven by a belief that the government agency is not the ultimate client needing to be served, as described by a PPL director: “We don’t call government agencies our clients. Government agencies are our partners, and we have a mutual client, which is the public. What we’re all working towards is increased opportunity for members of the public” (2019).

One learned best practice involves engaging an ‘agency leadership from the project outset. This group comprises executive and programmatic leaders who hold operational decision-making authority. As the future life of the project rests on project stakeholders’ shoulders, it’s important to cultivate ‘authentic trust’ so that the working relationship is sincere, reflective, and pragmatic (Solomon and Flores 2001). In the project plan, PPL outlines collaboration requirements to this end, including a request for a number of project partners to embed in the project team, attend fieldwork, and participate in internal work sessions. This invitation is similarly extended to the project funders. For Navigating Home PPL also worked with their primary government point-of contact to assemble a twenty- to thirty-person agency leadership group comprising staff who specialize in areas such as shelter operations, specific resident populations, staff training, and legal affairs. The group was kept abreast of project developments and attended ‘pin-up’ meetings following each project milestone, in which they contributed feedback and expertise to the project, as well as participated in co-design activities. These activities were essential for balancing user experience with operationally feasibility, and to help craft short- and long-term goals for implementation. Without this collaborative engagement the project team risked developing design work that lacked the necessary buy-in and operational backbone for successful implementation. Following project implementation PPL will also conduct a series of progress evaluation check-ins at the three-, six-, and twelve-month marks, so as to support their partners with arising challenges and the task of assessing project impact.

Reporting With Agency Coordination Tools

Throughout Navigating Home, reporting wasn’t a moment, but a process. Every meeting and pin-up contributed to the cumulative effort of equipping government partners and stakeholders with the stories, materials, and knowledge they needed to become advocates for the project and facilitate its implementation. This was a process of transferring agency through evidence-based storytelling that encouraged empathy for the people being served by the project, while also offering a pragmatic operational path forward, with the right level of strategic detail.

As the team regrouped after their penultimate pin-up, they noted that their stakeholder group and agency partners had focused on individual prototypes as catalysts for change. This was unsurprising, given that the team had been sharing discrete service interactions and their related prototypes in pin-ups, as compared to demonstrating distributed impact through the range of end-to-end service interactions they had been designing. Designing a service is ultimately about curating a flow of interactions, rather than a series of artifacts, as described by Akama: “designers are defined by what they enable, not what they ‘make’” (2009, 7). The team realized that they would need to better represent the deliverables at a systemic level, highlighting time, space, and human interaction, if to successfully convey the impact Navigating Home could make. The team therefore designed an ‘interaction model’ – a visual artifact that demonstrated resident and frontline staff interactions through one continuous, systemic experience, rather than a one-off interaction with a tool. While the tools they had designed could indeed be used independently, the team wanted to reflect fieldwork findings about client-centered, holistic, team-based models for work that suggested the tools would be most impactful when implemented together to support collaborative work practices. In their final presentation they breathed life into the interaction model by presenting it through narrative-based storytelling.

The team supplemented the system view with a set of policy and operational recommendations to address the issues that couldn’t be designed for within the scope of Navigating Home, but would nonetheless impact move-out rates immensely, if they could be addressed. These recommendations covered factors relating to staff training, suggestions for staffing and resourcing, conducting assessments, and both inter- and intra-agency workflow. These recommendations were shared with the belief that systemic impact can be greater when changes are made further up the power chain. Rather than frontline staff and residents largely shouldering the burden of responsibility for improved service outcomes, upstream policy changes could have significant flow-on effects: if programmatic agency staff are able to work more effectively within improved policy conditions, then they can better support frontline staff in their task of supporting residents.

CONCLUSION

Navigating power and agency in PSI design projects requires a thoughtfulness towards each aspect of the project’s making. PPL’s approach started with the team itself, reflecting on its practices and how the project should be planned and managed with respect to power and agency. As the project began, the team was scrutinizing its expression of agency, aiming to be sensitive during interactions with participants and maintain strict data collection protocols that protect participant privacy. However, as the project evolved, they realized that despite best intentions, there were limits to their agency as there were systemic factors that they simply couldn’t design for. Yet, when focusing on designing service interactions, the lens of agency became a pragmatic tool, as it helped identify the end users that would most benefit from their work, as well as the most appropriate areas for system intervention. The mindsets framework enabled them to see that some residents are ill-equipped to exercise autonomous behavior and that there will be limits to their self-actualization. When designing for frontline staff, the team had to recognize that they could not control for each shelter’s working culture and operational complexity; however it was possible to design for the common factors that impede a staff member’s ability to do their job well and encourage the factors that can support them. They focused on improved channels of support, training, models for internal collaboration, and building escalation pathways. And finally, the team sought to facilitate government agency partnership through close collaborative engagement strategies, such as embedding in fieldwork, co-designing in pin-ups, and strategic storytelling.

Ultimately, what evolved could be called a ‘reflexive practice’ that rests at the nexus of human-centered design and systems thinking. This practice requires a mindset and set of behaviors that ensure each user group is designed with and for according to their own unique circumstances. This also means that research is not an activity limited to fieldwork, but a constant process of information gathering that aids reflexivity. For Navigating Home, this meant considering how the homeless shelter system was impacting the lives of residents and frontline staff, as well as the ways in which their own actions and experiences were dynamically shaping it. This reflexivity extended into how the project team empowered its government partner to become a well-informed advocate for the work. It was also reflected in each team member’s desire to practice self-awareness and sensitivity – towards themselves, their team, and the participants.

Phase One of Navigating Home is already showing early signs of success. There is an enduring trust and spirit of collaboration between the team and their government partner. The partner has also set workstreams in motion that mirror the spirit and ethos of human-centered social service design. Yet reflexive practice is an enduring work-in-progress. The PPL team aspires to enrich their work with more peer-led, participatory design processes, to further their trauma-informed practices, and to make greater systemic impact through engagements focusing on policy design and experimentation.

Indeed, as more researchers and designers are drawn to PSI, and more public sector staff take up research and design activities, it is imperative that all practitioners become adept at working reflexively, and that practices continue evolving in response to the complexities of system-embedded power dynamics.

Natalia Radywyl is a multi-disciplinary researcher and designer working at the intersection of social innovation, systems thinking, and design. She received her PhD in Media and Communications and Australian Studies from the University of Melbourne, Australia, and is currently the Research and Evaluation Director at The Public Policy Lab. nradywyl@publicpolicylab.org

NOTES

This project could not have been completed without the generous support of the Robin Hood Foundation and our government agency partner. The author wishes to thank PPL’s Chelsea Mauldin, Erika Lindsey, and Shanti Matthew for offering editorial guidance and input, as well as the many project participants who selflessly shared their time, stories, and aspirations in aid of improving services at NYC’s homeless shelters.

Please note that the outlined project deliverables are currently in the process of being further developed and tested in a second phase of work, therefore may not reflect the final, implemented outcomes.

REFERENCES CITED

Akama, Yoko. 2009. “Warts-and-All: The Real practice of Service Design.” First Nordic Conference on Service Design and Service Innovation, Oslo, Norway November 24-26, 2009:1-11.

Blomkamp, Elizabeth. 2018. “The Promise of Co-Design for Public Policy.” Australian Journal of Public Administration, 77(4): 729-743.

Coalition for the Homeless. 2019. “Basic Facts about Homelessness: New York City.” Accessed August 30, 2019. https://www.coalitionforthehomeless.org/basic-facts-about-homelessness-new-york-city/

Donetto, Sara, Paola Pierri, Vicki Tsianakas, and Glenn Robert. 2015. “Experience-Based Co-Design and Healthcare Improvement: Realizing Participatory Design in the Public Sector.” The Design Journal 18(2): 227-248.

Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development. 2012. “STI Profiles: Building Competences and Capacity to Innovate – Public Sector Innovation.” OECD Science, Technology and Industry Outlook:181-182.

Pascale, Richard, Jerry Sternin, and Monique Sternin. 2010. The Power of Positive Deviance: How Unlikely Innovators Solve the World’s Toughest Problems. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

Pierri, Paola. 2017. “Decentralising Design. Raising the Question of Agency in Emerging Design Practice.” The Design Journal, 20(sup1): S2951-S2959.

Sanders, Elizabeth. 2008. “An Evolving Map of Design Practice and Design Research, November 1.” Accessed October 13, 2019, http://www.dubberly.com/articles/an-evolving-map-of-design-practice-and-design-research.html

Solomon, Robert. C., and Fernando Flores. 2001. “Authentic Trust.” Building Trust in Business, Politics, Relationships and Life, 90-152.

Van der Bijl-Brouwer, Mieke. 2017. “Designing for Social Infrastructures in Complex Service Systems: A Human-Centered and Social Systems Perspective on Service Design.” She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation, 3(3), 183-197.