‘AirSpace’, according to Kyle Chayka, is the increasingly homogenized experience of the western(ized) business traveller, driven by major tech platforms (including Google, Airbnb and Uber.) As international travellers, ethnographers must account for the impact of AirSpace on their research practice. After delineating the concept of AirSpace the paper posits three dangers ethnographers must negotiate: (1) The cost of control: AirSpace offers researchers control, but can narrow the scope of research (2) The risk of superficiality: AirSpace provides shortcuts to cultural understanding, but can limit deeper comprehension (3) The assumption of equivalence: AirSpace provides shared reference points, but can create the illusion of equivelance with research subjects. By exploring these three dangers the paper invites readers to reflect on their own research practice and consider how to utilize the benefits of these platforms while mitigating the issues outlined.

WELCOME TO AIRSPACE

“[In AirSpace] changing places can be as painless as reloading a website. You might not even realize you’re not where you started.”

(Kyle Chayka)

It has never been easier to conduct international ethnographic studies. International travel feels more frictionless and familiar than ever. If so inclined it would be possible to land at an airport, hail an Uber, check in to your Airbnb, locate a boutique café on Google Maps, and not be certain if you are in Shanghai, Stockholm, Sydney or Sao Paulo.

Kyle Chayka coined the term ‘AirSpace’ to describe the increasingly homogenized experience of the international business traveller, driven by major tech platforms: “the realm of coffee shops, bars, startup offices, and co-live / work spaces that share the same hallmarks everywhere you go”. AirSpace enables privileged travellers to traverse the world seamlessly, experiencing local culture at a comfortable distance, Flat White in hand, with a taxi never more than 3 minutes away.

Figure 1. Independent coffee shops in Shanghai, Stockholm, Sydney and Sao Paulo (source: Pintrest)

As privileged travellers, AirSpace will be familiar to many corporate ethnographers. International platforms like Airbnb, Uber, Facebook and Google Maps have all become integral to the logistics and practice of modern fieldwork. From organizing accommodation to recruiting respondents, through to finding a quiet place to write up field notes, these services offer convenience, comfort and efficiency, as well as significant cost savings.

But ethnographers must be mindful. AirSpace represents more than a convenient mode of travel or aesthetic choice. It is part of a deeper technology-driven shift that reframes how we view and experience the world, with important implications for how we gather and martial evidence. From impacting how we frame our studies, subtly shaping our experience of the world, through to making assumptions about the people we are studying, AirSpace has important implications for ethnographic practice.

In this paper I will interrogate the impact of AirSpace on corporate ethnography, drawing on the experiences of practitioners across studies in three continents.

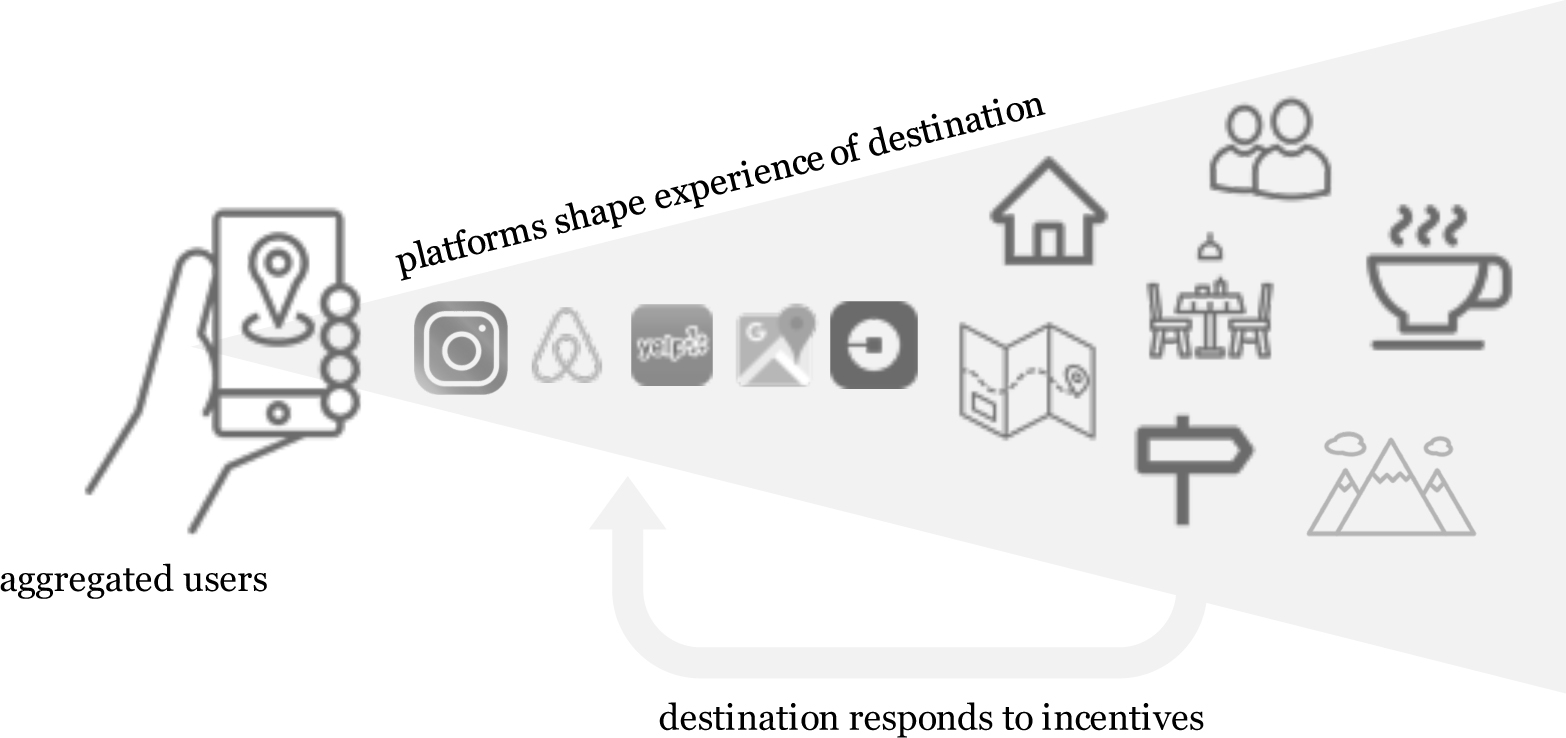

THE USER EXPERIENCE OF MONOPOLY

Before we discuss AirSpace’s implications for research, we need to further clarify the term. What makes internet companies like Google, AirBnb, Facebook, Instagram, Uber and DiDi distinctive is not only their capacity to scale their services seamlessly for millions of users, but that the user experience generally improves as the number of users increases. In the words of Ben Thompson, these companies ‘aggregate’ users by maintaining a virtuous circle in which they “become better services the more consumers/users they serve — and they are all capable of serving every consumer/user on earth.” (Thompson, 2015)

And if just one or two companies dominate a specific market then, inevitably, the ‘user experience’ of that constituency becomes standardised. For many users searching becomes ‘Googling’; Facebook is social networking; Airbnb becomes our default means for finding holiday accommodation. As we shall see, this is not to claim that these platforms monopolize all users. Or that users experience them in the same way. But it is to point out that the aggregation of a specific groups of users is having a significant impact on the way places and markets are framed, understood and served.

Chayka argues that the effect of these platforms is to privilege specific kinds of products and experiences, driven by the tastes of their most frequent and ‘valuable’ users: affluent and westernized. This is why many coffee shops – from large chains like Starbucks to independent businesses – look the same around the world. Or why AirBnbs often seem to have the same furniture. Suppliers look at what is succeeding on these platforms and ape the same style and proposition, creating convergence. As Chayka puts it:

You can hop from cookie-cutter bar to office space to apartment building… You’ll be guaranteed fast internet, strong coffee, and a comfortable chair from which to do your telecommuting. What you won’t get is anything interesting or actually unique. (Chayka, 2016)

Figure 2.

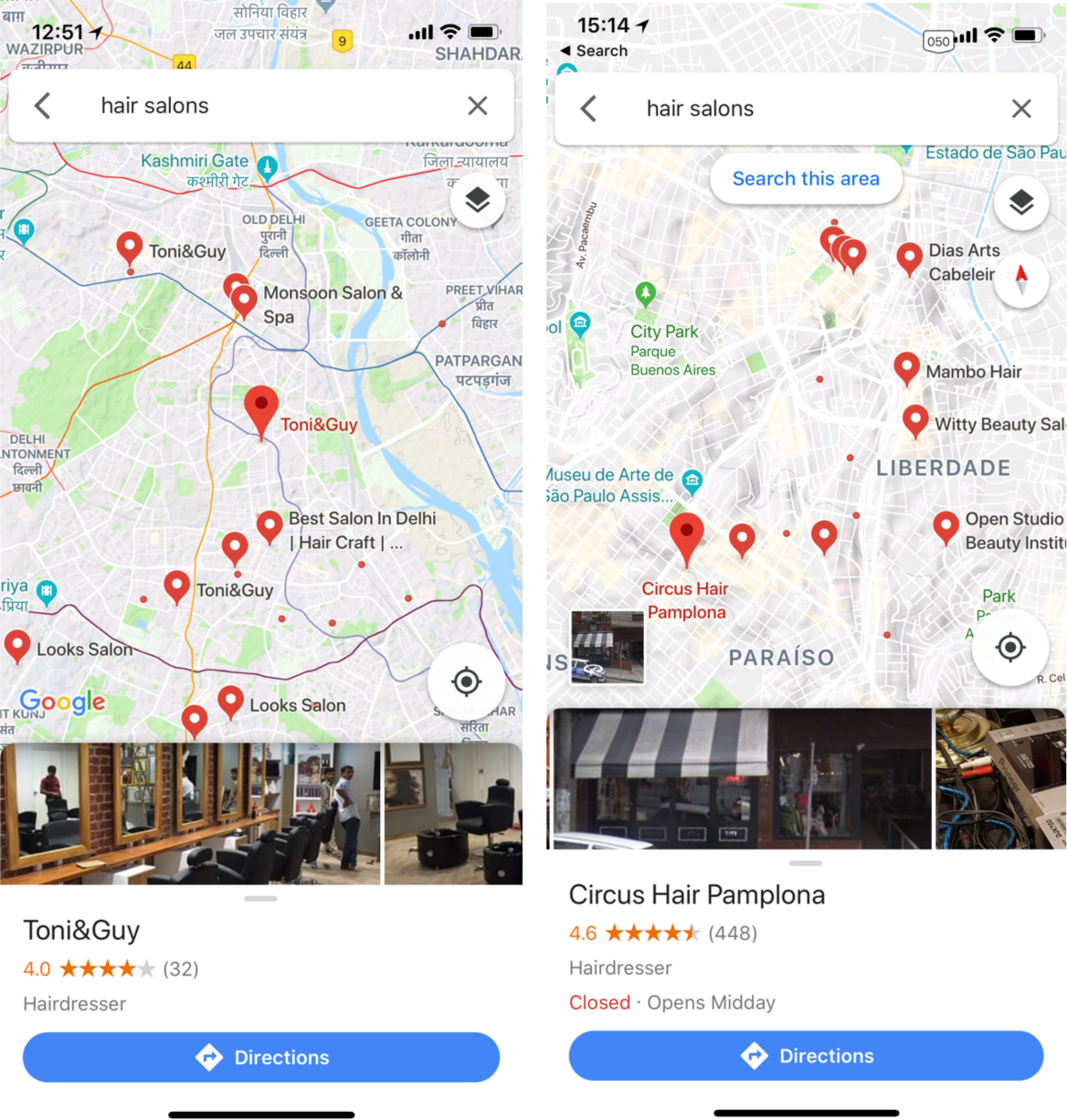

Let’s explore a tangible example. Imagine the same American tourist arriving in Delhi and Sao Paulo. On both occasions the tourist needs a haircut. She gets out her phone and searches for “Hair Salons”

Figure 3. Discovering Hair Salons in Delhi and Sao Paulo through the same Google Maps interface

From a software perspective, the experience is almost identical. Google Maps presents itself as a neutral encyclopaedia that reflects all available options. The visuals and text of each salon are shaped by what the interface prescribes.

But the results are unlikely to be exhaustive. And the best reviewed salons are similar: they tend towards the expensive and westernized. They reflect the specificity of Google’s users, and, by extension, the businesses and places that best address their specific needs. Whether the tourist is in Dehli or Sao Paulo, the experience – from the interface to the places she finds – share many commonalities. Of course, as a user of Google Maps this can be highly comforting. Wherever we are in the world we know not just how we will find a Hair Salon but also what kind of Hair Salon we will find.

AirSpace, then, is the user experience of monopoly. It describes what it feels like when platforms shape how their specific user base is served from discovery to consumption across geographies. This is not to claim that this experience is true for all consumers: most people around the world do not use these platforms frequently. And most places and businesses remain outside of AirSpace. But it is a common experience for many privileged travellers who use these platforms to navigate the world, including ethnographers.

Kyle Chayka and others have explored the aesthetic implications of such convergence. But what does it mean for how we understand the world as researchers? As frequent occupants of AirSpace, there are important implications. I want to highlight three dangers I believe it creates.

- The cost of control: AirSpace de-risks research by making it more predictable (so you can deliver on time and on budget), but can remove opportunities for spontaneity and narrow the scope of research

- The risk of superficiality: AirSpace can make the world more comprehensible, but applies pre-made categories and labels to culture, providing easy shortcuts that can derail deeper understanding

- The assumption of equivalence: AirSpace can provide common reference points with the people we are studying, but encourages us to falsely equate our own experience with their own

But first I want to share a fieldwork story to provide some context for these claims.

ENTERING CHINESE AIRSPACE: A VIGNETTE

Following an 11-hour flight I felt disorientated. As we touched down I fired up the VPN I’d installed the day before, hoping to re-connect. Nothing. As feared, my phone would need a local Chinese SIM card. This made me anxious. Our flight was delayed and I wanted to let our AirBnb host know that we were running late.

With the help of my Mandarin speaking colleague we acquired a SIM at a kiosk at the terminal. I felt uncomfortable handing my iPhone to the clerk as she played with the settings. After several minutes the clerk handed the phone back. WhatsApp and Instagram began populating with updates: a warm feeling of familiarity cast over me as recognizable names appeared on the screen. Once again, I felt in control.

Figure 4. Author with translator and client, Shanghai, 2018

I opened the Airbnb app to contact our English-speaking host. We had chosen to stay in an ‘authentic Shanghainese town house’ in the French Concession with excellent reviews from other Western travellers (and a few Chinese!) This would be our research base for the week.

Our team was in Shanghai to study the automation of Chinese shopping practices. We had recommended Shanghai to our client because it was a sophisticated retail market, but also because of its accessibility – we knew we could be “in and out” within six days and stay on budget. In preparation for our trip we had used a combination of Google and local contacts to identify new examples of retail automation. (We were later to discover this provided us with a highly superficial understanding of what was going on. Many of the places we identified were either no longer operational or did not represent the cutting edge, forcing us to adapt our plans mid fieldwork.)

My colleague used DiDi (China’s answer to Uber) to hail a taxi to the house. DiDi wasn’t as quick as getting the train but it meant we wouldn’t have to deal with buying a ticket or negotiating the subway. During the ride I played with Google Translate’s augmented reality feature to try to figure out the text on the dashboard. “Business Bus Driver” it read. Makes sense, I thought, but is that how Shanghainese people understand it? The poor translation prompted more questions than answers, which, on reflection, I felt was a good thing.

We had an hour or so until our first interviews and we hadn’t eaten lunch. I loaded up Apple Maps to see what I could find: a coffee shop was just around the corner. I was tempted to stop by a bustling ‘local’ restaurant we passed on the way. But a quick check showed there were no English reviews online, and we didn’t know how long it would take to get served. Better to not take the risk and make ourselves vulnerable to the unknown.

My translator Rong met me at the coffee shop and we travelled via DiDi to our first interview in a northern suburb of Hongkou. I was glad we travelled together because she explained en route the cultural context of the neighbourhood we were visiting – it was known locally for its excellent schools and therefore attracted wealthy young parents. I started to see the generic apartment blocks we were passing in a different light. I noticed the number of prams being pushed around on the sidewalk. And the surprising number of luxury boutiques. For the first time since I arrived I felt a flicker of insight spread over me. As we stepped into the apartment block I couldn’t wait to learn more.

THE COST OF CONTROL

Airbnb, Apple Maps, DiDi, WhatsApp, Instagram: the services highlighted by my experience in Shanghai will be familiar to many corporate ethnographers. The promise of these international platforms is alluring. Never has it been simpler to locate optimal research fieldsites on Google Maps, situate yourself in a ‘local’ Airbnb, or move seamlessly between interviews in an Uber or DiDi. These generic, familiar interfaces remove the friction of local complexity whilst cutting lead times and costs. In short, being in AirSpace means feeling in control.

The alternative to control is stress. A colleague recently conducted fieldwork in Germany on behalf of a large chemicals company. The study involved speaking to a very specific audience: welders in small manufacturing businesses in rural Germany. Her experience of the fieldwork was fraught because she had little control over its organization and execution.

The researcher was entirely reliant on her client and her client’s customers to conduct the fieldwork. Each day she was driven to a field-site (which she had no prior knowledge of) and was then expected to convince unsuspecting workmen to speak to her about their welding practices. On some occasions the workers couldn’t spare any time and she would leave empty handed.

“We had no idea who we were going to speak to… there was much more risk to it… no predictability”

What made the project particularly stressful was the time pressure the researcher was under. Budgets and deadlines dictated when the research had to be ‘finished’ (rather than the satisfactory obtainment of data).

This is nothing new. Corporate ethnographers have always been under pressure to speed the research process up. But it explains the context in which AirSpace platforms are being adopted. The convenience, predictability and control they offer provides new opportunities for making the research process more ‘efficient’.

Take my personal experience in Shanghai. It was characterized by the removal of friction by platforms that felt safe and familiar to me. This reduced my stress levels and made me feel in control of the situation. But I chose to use them because they offered comfort and speed, not because I believed they would make me a better researcher.

As another researcher put it, “when you’re doing research you are acting so abnormally because of lack of time… these apps speed things up.” (Practitioner interview 1, 2018)

However, speed is not always conducive to quality research. Many ethnographers feel that negotiating local complexities and the unforeseen situations that they give rise to is often the source of the richest and most lateral insights. Despite the stress of the fieldwork the German welding project proved a success precisely because of its spontaneous, unplanned nature:

“[The unplanned nature of the project] meant we came across complete gems… there was a worker we came across who turned out to be the star… it was lucky: he was waiting for something so we could speak to him in legitimate downtime… The pros [of messiness] outweigh the cons…as a researcher you need to be more ethnographic… you have to put yourself out there more… you’re on the line.”

The pressure of the project meant the researcher wanted to make things easier for herself, but this intention, she later recognized, was “serving myself not the ultimate goal of the project”. The consequence of this can be to undermine the quality of the research itself: “you can try and make it frictionless but you can end up with very clinical projects” (Practitioner interview 1, 2018)

This is not to say that using these platforms is necessarily damaging. Oftentimes making fieldwork more controllable is the right thing to do. For example, saving time on getting around town could mean more time for note writing and reflection at the AirBnb. But in a context in which timescales are being constantly squeezed AirSpace often has the opposite effect: reducing the space for proper ethnography by creating further ‘efficiencies’.

In this sense Google, AirBnb, Uber and their ilk facilitate a world in which it is possible to reduce ethnography to no more than 3 hour in-home interviews (Sunderland and Denny, 2013) through the alleviation of the ‘friction’ that surrounds their organization and execution. In doing so AirSpace enables the narrowing of our frame of reference from people and places to ‘users’: “the clean language for describing the messiness of people – deracinated from their contexts” (Amirebrahimi, 2016).

Time outside of the interview is no longer considered ‘research’, but ‘down time’ in which the researcher can return to the comfort of AirSpace. One client researcher demonstrated this last year on another project in China. Rather than venture out of her Chengdu AirBnb to sample the local cuisine she ate from her stash of protein bars, imported with her from the US. This is not to say she would have necessarily learned anything valuable during the meal, but not participating in it certainly precluded the possibility. And AirSpace makes it easier to choose not to participate.

When ethnography is reduced to interviews its perceived value and utility in corporate settings is also undermined. Highly structured fieldwork is less suited to foundational questions that require abductive reasoning. In isolation interviews are good for addressing narrow challenges: rapidly testing and iterating existing hypothesis rather than challenging underlying assumptions. It is in this sense that AirSpace is facilitating what Simon Roberts has termed the ‘Uxification of research’ (Roberts, 2018) by creating the conditions in which ethnography can be bracketed to interviews.

But the danger of AirSpace extends further: it also informs how we experience the world as researchers.

THE RISK OF SUPERFICIALITY

In 1995 Marc Auge made a distinction between places and non-places. Places are characterised by their rich cultural content: “complicities of language, local references, the unformulated rules of living know-how” (Auge, 1995). Non-places, in contrast, are characterized by temporary identities and generic labels: passengers in airports, customers in supermarkets, freelancers in coffee shops.

International technology platforms have commodified the most obscure, exotic places by making them superficially accessible. Search Airbnb for Mongolia and the first result is an invitation to stay in a ‘Private Room in Yurt’ with a ‘Mongolian Nomadic Family’. While not as generic as ‘customers’ or ‘passengers’, these simple labels make Mongolia feel familiar and available. In Auge’s terms, places that would have taken serious time and effort to experience, can now be consumed as non-places through these platforms. Place and non-place are becoming increasingly conflated.

Figure 5. Nomadic lifestyles are now a click away, Airbnb

The role of the ethnographer is to embody, surface and translate the ‘living know-how’ of place for their audience. But in a world of tight deadlines and shrinking budgets it’s easy to cut corners and consume places superficially, utilizing the shortcut AirSpace platforms afford.

Comparing research studies in the US and China, a fellow UK-based researcher described how in the US fortuitous circumstances gave him the opportunity to get his ‘bearings’ and sense of place by simply becoming familiar with a local bar. In China, by contrast, a lack of time meant he could only experience place superficially.

“On a recent trip to Cincinnati we happened to be there a few days early and we stumbled upon a bar which ended up being an important piece of the research… in China I never had the time to figure out what was happening around me… with more time I would have gained my bearings… sometimes it takes an hour, sometimes a week” (Practitioner interview 2, 2018)

When there is no time “to figure what is going on around me” we naturally look for shortcuts. AirSpace is an increasingly attractive substitute to a deeper understanding because it presents the world as instantly accessible and consumable. The danger is that as researchers we take these pre-existing labels as read and don’t probe them further.

In a recent trip to Zurich a colleague and I were conducting a study on ‘knowledge workers’ for a technology firm. We wanted to understand their lifestyle outside of work so we decided to eat at a ‘local’ restaurant for our first evening in the field. Instinctively I pulled up Yelp to find a restaurant, figuring if it was popular on Yelp it would be popular with local people.

When we arrived at the top recommendation we noticed the signals Chayka describes as characteristic of AirSpace: raw wood tables, Edison bulbs, industrial furniture. And the rucksacks and accents dotted around other tables made it clear that were surrounded by other short-term visitors. We quickly realised we wouldn’t learn much about the experience of local workers here.

Figure 6. Discovering ‘local’ cuisine through Yelp

The mistake we’d made, of course, was to assume Yelp provided a ‘local’ perspective when in fact the people who use the app skew a specific way: American, white, middle class. Unlike Lonely Planet or other self-described tourist guides Yelp’s stated purpose is neutral “to connect people with great local businesses.” But what is considered ‘great’ reflects the cultural specificity of its user base, not necessarily a universal or even local perspective. Like the other coffee shops and bars we later encountered in Zurich, this restaurant had clearly been tailored to the tastes and needs of the western business people and tourists.

It is in ‘breakdown’ moments when experience does not meet expectation, that the edges of AirSpace appear and we can re-orientate ourselves as researchers. In the earlier Shanghai vignette, the fact that Google Translate provided an off-kilter translation of the local taxi service made me question how local people think about taxis: it made me more aware of how much I didn’t know.

Figure 7. Google Translate reveals the ‘edges’ of AirSpace

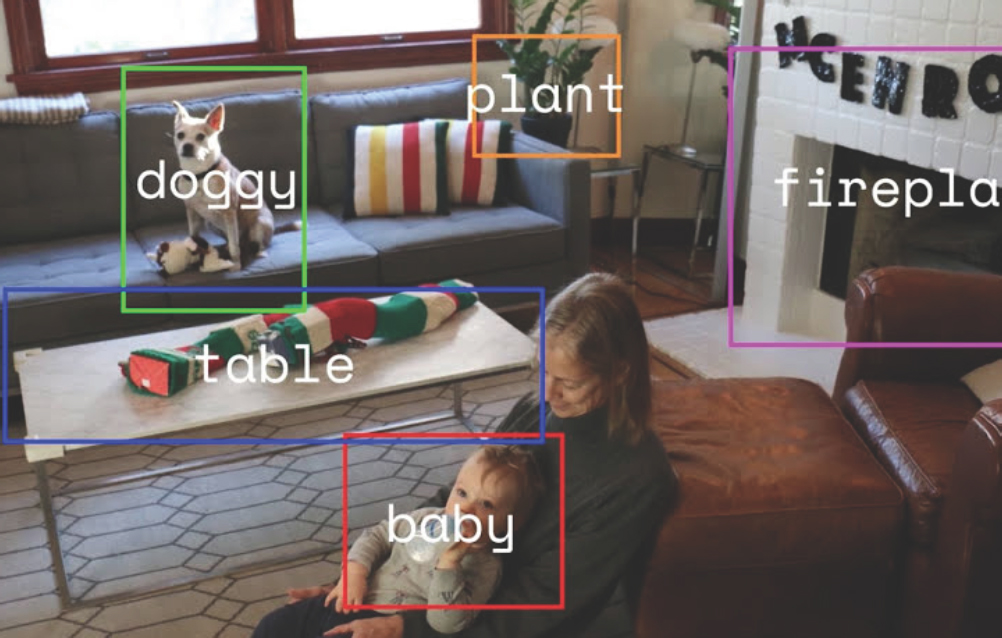

These imperfect experiences make us better researchers by surfacing the limitations of our understanding; revealing the borders between our own worlds and the worlds we are seeking to understand. But how much longer until these imperfections are ironed out and we mistake AirSpace for the world we are seeking to understand? Because culture is being labelled and translated with growing fidelity.

Figure 8. Google’s visual recognition makes every object ‘readable’

Google continues to ‘organize the world’s information’ through visual and audio recognition technologies. At the most recent I/0 conference, CEO Sundar Pinchai demonstrated Google Assistant’s new capacity to book appointments at local businesses. This technology will be used, in part, to harvest information that is currently ‘off grid’ because the local business has not shared that information with Google pro-actively (for example opening and closing times, what’s on the menu etc).

Given this technological trajectory it is conceivable we will find ourselves in a situation in which every minor aspect of global culture – from buildings to market stalls to people in the street – are instantly recognizable, objectified and labelled by these platforms, our perceptions shaped by how they are presented to us.

As our cultural topography is mapped with growing fidelity there will be a temptation for researchers to consume culture superficially through these easy shortcuts to understanding without considering the tacit perspectives and agendas that frame them.

But interrogating these biases is easier said than done. As the fidelity and ubiquity of AirSpace intensifies, so its borders become increasingly difficult to disaggregate.

THE ASSUMPTION OF EQUIVALENCE

“It is difficult to see what is always there. Whoever discovered water, it was not a fish”

(Geertz) p259

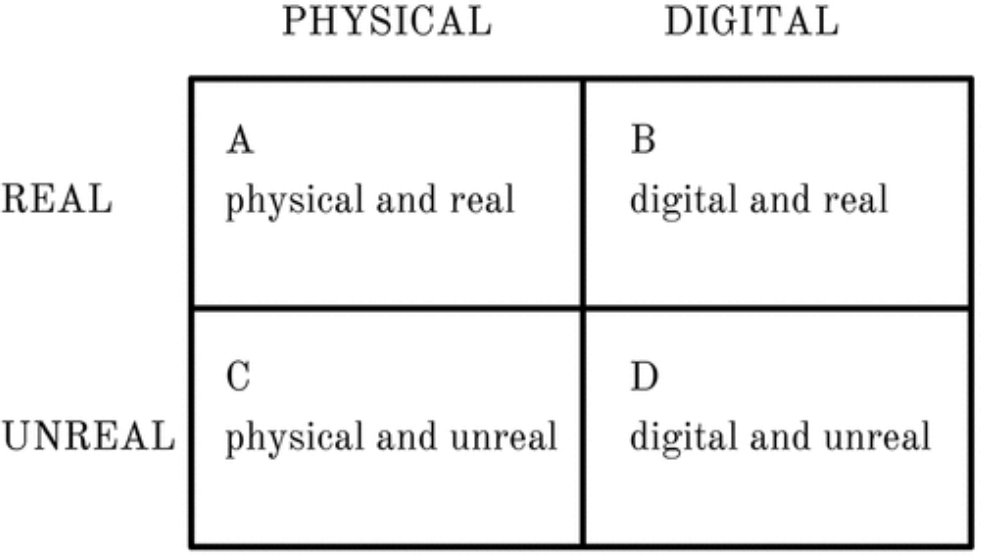

Tom Boellstorff argues that we make a fundamental mistake when we frame the physical world as ‘real’ and the digital world as ‘unreal’ (Boellstorff, 2016). He suggests that both the digital and physical are equally capable of incorporating real and unreal phenomena. In his sense, losing money gambling online is as real as losing it offline. While daydreaming at work is unreal as daydreaming in the middle of a video game.

Figure 9. The Digital Reality Matrix (Boellstorff, 2015)

At the same time, this does not mean the digital and physical are two sides of the same coin. They remain distinctive phenomena capable of generating separate realities, and should not be assumed equivalent.

For instance, if someone living in Chicago posts on Facebook, it is misleading to assert that this posting is located “in Chicago,” even though that is where the poster’s physical body is located… If 15 friends responded with comments, their activity would not be located “in Chicago”; these friends may not even live in Chicago. They could be posting while walking on a street with a mobile device or even while using a tablet on an airplane at 30,000 feet. In the sense of social action, these activities occur “on Facebook.” The online sociality is real not in an exhaustive or privileged sense but in a perspectival sense.” (Boellstorff, 2011)

What makes AirSpace distinctive is that it straddles the digital and physical worlds, shaping our experience of both. You are never clearly ‘in AirSpace’ in the sense you can be ‘on Facebook.’ Think about the earlier example of searching for hair salons in Shanghai and London using Google Maps. Both the digital aspects (discovering the salon) and physical aspects (the appearance of the salon itself) of the ‘user experience’ are influenced by the content and aesthetics that are rewarded or sanctioned by the platform. Compared to Boellstorff’s Facebook example (a relatively bounded digital world) the impact that Google Maps has in this case is at once more extensive and subtle.

This has serious implications for research. The unified experiences these international platforms offer tacitly shape our research choices: what places sound interesting; the easiest route to navigate; how to read a particular neighbourhood. But despite the tacit claims to universality the representation is always particular and usually reflective of a specific affluent user base. As Chayka explains

AirSpace creates a division between those who belong in the slick, interchangeable places and those who don’t. The platforms that enable this geography are themselves biased: a Harvard Business School study showed that Airbnb hosts are less likely to accept guests with stereotypically African-American names. (Chayka, 2016)

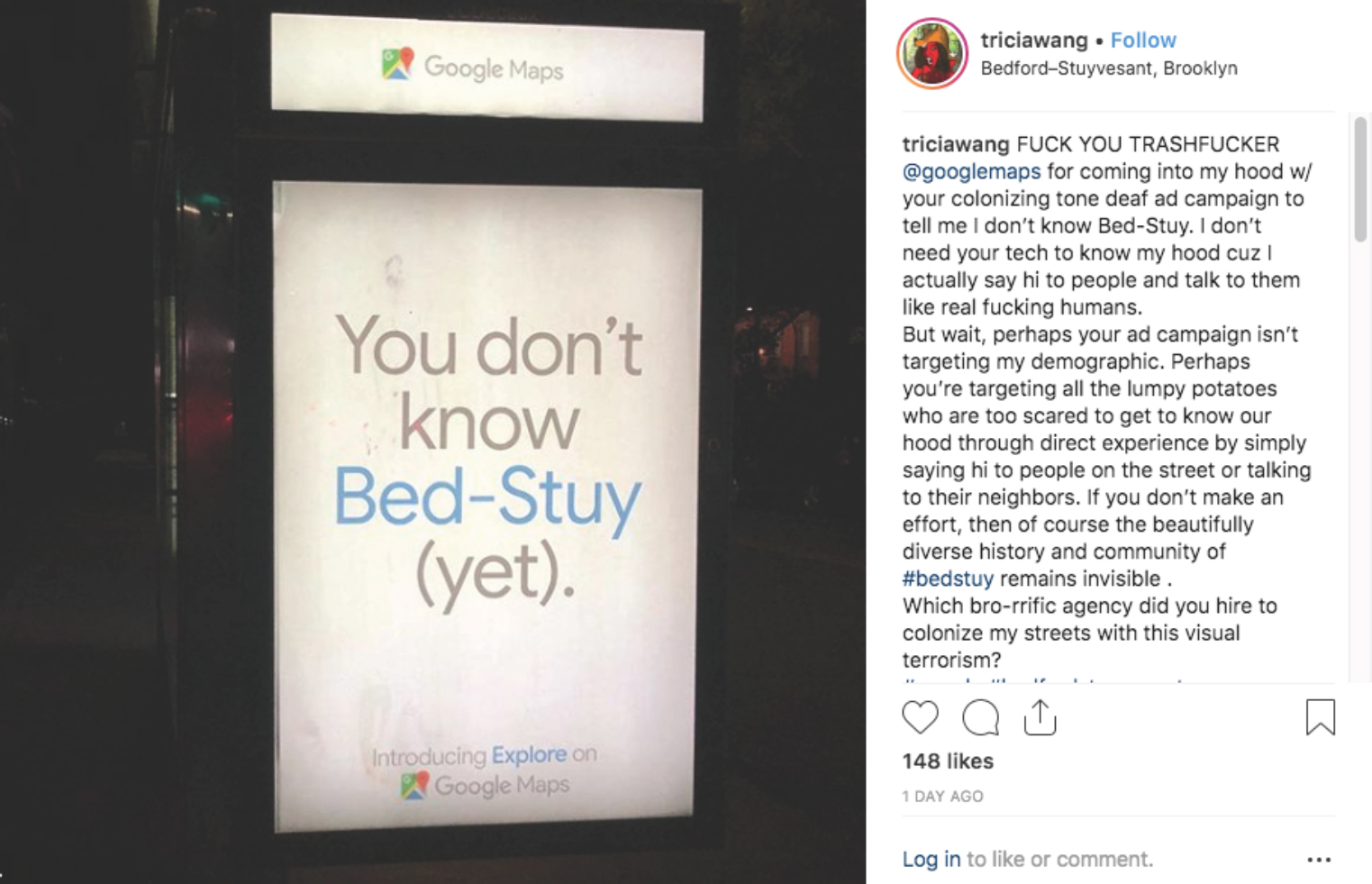

Ethical concerns notwithstanding, this has serious implications for how we understand the world as researchers. EPIC contributor Tricia Wang recently encountered ads for the Google Maps Explore feature in Brooklyn, and reacted strongly against what she deemed the creeping cultural ‘colonialism’ of tech companies.

Figure 10. Google Maps labels (and defines) local cultures through its new ‘Explore’ feature, Brooklyn

Wang contrasts the perspective offered by Google Maps with the richer perspective of people who try to understand the world through “direct experience” by saying “hi to people”. She rejects the “colonizing” attempt of Google Maps to read her neighbourhood neutrally when, in fact, it promotes a situated perspective aimed at new residents and non-resident visitors / tourists.

As a resident of Bed-Stuy, Wang can delineate between these perspectives. But as a visitor seeking “direct experience” can make us feel vulnerable, and occupying AirSpace is certainly more convenient.

As the fidelity of AirSpace improves and the ‘breakdown’ moments that trigger self-awareness are ironed out, our capacity for reflexivity is diminished. And when we are no longer reflexive we assume equivalence: my reality is the same reality as the people I am studying.

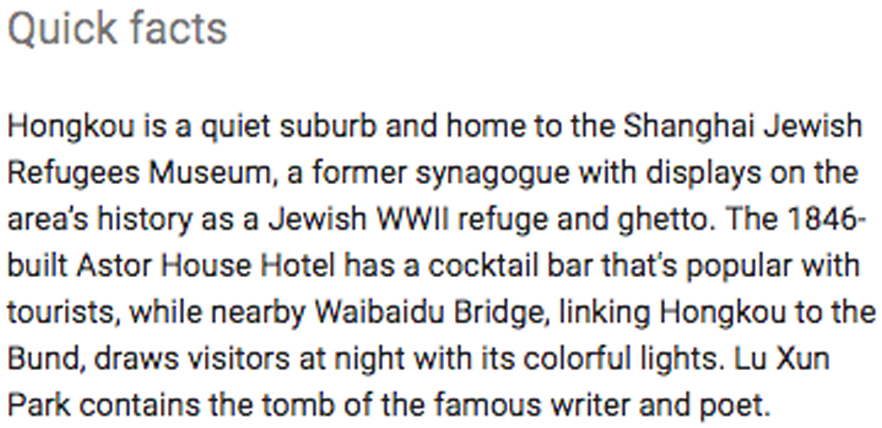

Let’s return to the Shanghai vignette at the beginning of the paper. When I was introduced to the district of Hongkou by a local translator she pointed out specific aspects to me (relevant to my objective of understanding local retail practices) – the prevalence of young affluent families, good schools and luxury children’s boutiques. Alternatively, had I used Google Maps as an introduction to the neighbourhood I would have focused on entirely different aspects:

Figure 11. Google Maps description of Hongkou, Shanghai

The point here is not to say that Google Maps is wrong to focus on these aspects of the neighbourhood. The content reflects the interests of the majority of its users. The issue is that, unlike self-described tourist guides, it presents the information as neutral, up-to-the-minute and totalizing. And as a researcher it is easy to start to make unguarded assumptions: that these features of Hongkou are important for local people too.

But the danger of equivalence extends further still. Not only can we project the reality of these platforms onto non-users, we can also wrongly assume that users themselves are equivalent. In a study of Facebook usage in Trinidad, Miller demonstrates “where the potential for gossip and scandal (and generally being nosy) is taken as showing the intrinsic ‘Trinidadianess’ of Facebook.” (Horst and Miller, 2012) He argues that Trinidanian Facebook is a distinctive reality compared to Facebook in other cultures, even if the generic interface is precisely the same. Just because two people use the same interface doesn’t mean they interpret or use it in the same way, even if usage seems equivalent at a surface level.

This is not to descend into a relativist vortex and claim that no two experiences can be equated, but rather to warn that our job as researchers is being made more complex by AirSpace. The assumption of equivalence occurs when we mistake the representations of AirSpace as shared by the people we are studying. And when we believe that our “reality” of technology usage is equivalent because, on the surface, it looks the same.

LOCATING THE ‘WORLD AROUND HERE’

“…there is no such thing as pure human immediacy; interacting face-to-face is just as culturally inflected as digitally mediated communication, but, as Goffman (1959, 1975) pointed out again and again, we fail to see the framed nature of face-to-face interaction because these frames work so effectively” (Horst and Miller, 2012).

Our response to AirSpace should not be to retreat from it and return to an ‘unmediated’ ‘pre-digital’ time. As Miller and Horst explain, such a time has never existed. And the sheer utility and convenience offered by these platforms ensures they will remain crucial to ethnographic practice in the future.

Which means as the experience of AirSpace becomes all-encompassing we need to work harder to reveal its borders and reflect on the contingencies of our own experience. As Geertz puts it “…no one lives in the world in general. Everybody, even the exiled, the drifting, the diasporic, or the perpetually moving, lives in some confined and limited stretch of it – “the world around here.” (Geertz, 2004)

By focusing intensely on ‘the world around here’ we can mitigate the dangers posed by AirSpace.

- We can question whether the feeling of control AirSpace offers is undercutting the quality and scope of our research. When does removing friction from fieldwork help the work and when does it hinder the work?

- We can situate and interrogate the simple labels and categories that AirSpace provides to push beyond a superficial understanding.

- And we can reflect on how AirSpace promotes a particular perspective parading as universal, and how our experience of technology is the same or different from the people we are seeking to understand.

The stakes are high. When we fail to account for AirSpace we not only fail as ethnographers, we can become agents of a broader totalizing phenomenon. These are international platforms that present themselves as neutral but in fact interpret and shape the world from a particular point of view. Our job is to reflect on and problematize their role in impacting our experience of the world, as well as the world itself, while leveraging them for their undoubted value.

REFERENCES

Amirebrahami, Shaheen

2016 The Rise of the User and the Fall of People: Ethnographic Cooptation and a New Language of Globalization. Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings

Auge, Marc

1995 Non-Places: Introduction to an anthropology of Supermodernity. Verso

Boellstorff, Tom

2015 For Whom the Ontology Turns: Theorizing the Digital Real. Current Anthropology 57, no. 4 387-407

Boellstorff, Tom

2012 Rethinking Digital Anthropology. In H. Horst and D. Miller, Digital Anthropology Bloomsbury

Chayka, Kyle

2016 Welcome to AirSpace. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2016/8/3/12325104/airbnb-aesthetic-global-minimalism-startup-gentrification

Chayka, Kyle

2016 Same old, same old. How the hipster aesthetic is taking over the world. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/aug/06/hipster-aesthetic-taking-over-world

Geertz, Clifford

2004 “Afterword.” In K. Basso and S. Feld, Place. Tourism and Applied Anthropologists: Linking Theory and Practice.

Horst, Heather and Daniel Miller

2012 The Digital and the Human: A Prospectus for Digital Anthropology. In H. Horst and D. Miller, Digital Anthropology Bloomsbury

Knox, Hannah and Walford, Antonia

2016 “Is There an Ontology to the Digital?.” Theorizing the Contemporary, Cultural Anthropology website March 24, 2016. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/818-is-there-an-ontology-to-the-digital

Roberts, Simon

2018 The Uxification of Research. Stripe Partners Website. http://www.stripepartners.com/the-ux-ification-of-research/

Sunderland, Patricia and Rita Denny

2013 Opinions: Ethnographic Methods. Journal of Business Anthropology 2(2): 133-167

Thompson, Ben

2015 Aggregation Theory. Stratechery Website. https://stratechery.com/2015/aggregation-theory/