This paper reflects on the evolving nature of ethnographic praxis in industry and argues that we must move beyond research and towards strategy in order to elevate our praxis, and to deliver real impact and value for our clients. Although this conversation is not new for the EPIC community, there has been a lack of models and examples – even in its tenth year – for how to do so. Taking a project with a medical device company that manufacturers voice prostheses for laryngectomees as a case study, we show how a team of social scientists used “Sensemaking” to determine a new commercial direction for innovation and to design a five-year portfolio strategy for our client. In doing so, we illustrate how our praxis can do more than deliver research insights or design, but also act as the core foundation that defines business processes and strategy.

INTRODUCTION: THE CHALLENGE WITH OUR PRAXIS TODAY

Over the last decade, ethnographic research has become an established and well-used methodology in the corporate world (Cefkin, 2009; Morais and Malefyt, 2010; Mack and Squires, 2011). Many companies routinely hire anthropologists to provide insights into their consumers, while others have set up their own in-house consumer insights divisions. Traditional management consultancies are increasingly acquiring or partnering with research and design firms1, and business schools have even begun to teach ethnography as a research methodology (Jordan, 2010; Squires et al., 2014; Gebhardt, 2015). The need to prove the value of ethnographic research in the business world has long diminished, and our industry practitioners can be found working in all industries and business units. As Christian Madsbjerg noted in his 2014 EPIC Keynote, ‘‘the skeptical conversations about our methodology are over. We won.’’ So what’s the problem?

While ethnographic praxis in industry has grown tremendously over the years, the depth at which it penetrates a company’s overall direction and strategy has been relatively minimal. One consequence of putting our focus on proving the value of ethnographic research in the early years is that we’ve inadvertently defined the boundaries of our practice around consumer research. Despite the push to move into strategy, many of our practitioners today still have little role in implementation or execution, and rarely see the final results. Many practitioners only work with marketing or research and development divisions, with little engagement with executive management or strategy teams. This is especially true for practitioners who work in consulting firms, or independently and are unaffiliated with any one company.

One reason why we’ve been so far removed from strategic decision-making is that businesses don’t fully trust us – we are perceived to be experts in people, but novices in business (Morais, 2014). Businesses are cautious to allow us to make big decisions that may impact their top-line for years to come, especially if they feel that we lack knowledge of how their industry or corporation works.

The other reason, however, is that our industry as a whole has yet to move beyond research. Over the years, we’ve positioned ourselves as user researchers, design thinkers, and even as “storytellers,” but one consequence of doing so is that clients are inclined to see the value of our praxis only in its ability to provide research insights. Today, clients come to us primarily when they’re looking for an ethnography, which as Sunderland and Denny (2013) describe, has been rendered a three to four hour at-home interview with a pre-recruited individual. This particular type of ethnographic research has become a commodity (Baba, 2014; Morais, 2014), just another item on the corporate “to-do list” that businesses outsource to market researchers, innovation consultants, designers or academics in order to keep up with industry norms and stay relevant in an ever-changing globalized world. But therein lies the challenge – partaking in only this type of work fuels the “de-skilling” (Lombardi, 2009) of our industry practitioners, reducing anthropologists and sociologists to laborers who can only conduct piecemeal tasks for clients.

It has been a challenge to elevate our praxis when it is perceived to be a commodity. However, moving beyond research and into strategy may be key to reversing this commodification, allowing us to position ourselves at the higher end of the services market to become more valued and trusted advisors to our clients (Baba, 2014). While we recognize that there has been a new breed of consultancies that bridge research with strategy, and a growth in business anthropologists who inform strategy and organizational change (Squires et al., 2014), the challenge still lies in elevating our praxis as a collective whole to the realm of strategy. If we fail to respond to this commodification of our praxis, we run the risk of becoming irrelevant even as ethnographic researchers. What if our praxis is reduced to the selling and writing of fieldwork guides to clients, who then carry out research themselves?

This year’s theme, Building Bridges, invites us to explore the ways our praxis can move beyond research and towards strategy in order to build stronger, more meaningful bridges to our clients and their companies. This conversation is not new for the EPIC community: Bezaitis and anderson (2011) wrote about the need to claim responsibility for translating insights and for getting companies to act on them; Hasbrouck (2015) discussed applying ethnographic thinking to various stakeholders in order to move “beyond the toolbox”; Morais (2014) wrote about the need for anthropologists to take an active part in strategy codification; and at the end of his 2014 keynote, Christian Madsbjerg asked our community to ‘‘grow up’’ and to take our work more seriously by focusing on larger, more strategic problems.

While there has been a wealth of discussions for why we should move our praxis into strategy, there has also been a lack of models and examples for how to do so. The purpose of this paper is to provide a case study, based on a project we conducted with a small medical device company that manufactures voice prostheses for laryngectomees, to show how our team of social scientists used “Sensemaking” to deliver strategic and cultural change at a company-wide level. We discuss how our team became the pivot of the company, working in close collaboration with marketing, engineering, sales, and executive management (both respectively and collectively) to set a new commercial direction and process for innovation. This new direction became the foundation for building an overarching portfolio strategy for the company for the next five years.

In addition, we show how our team played a fundamental role in re-energizing and re-motivating the company’s employees after years of rote practice by bringing about a cultural shift in thinking and attitude towards laryngectomy. In doing so, we illustrate how our praxis can do more than simply deliver research insights or design; it can also act as the core foundation that defines business processes and strategy.

BACKGROUND: SETTING A NEW DIRECTION FOR LARYNGECTOMY

In 2014, a small medical device company approached our firm with one big problem: the company was looking to grow its position in the market with new product and service offerings, but they lacked the direction for innovation. The company (subsequently referred to as ‘‘MedCo’’) produced medical devices for people suffering from ear, nose, and throat medical conditions – with one core customer group being laryngectomees.

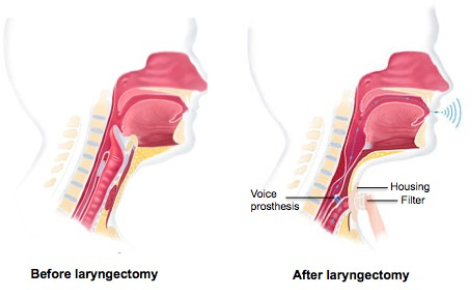

Laryngectomees are people who have had their larynx (i.e. voice box) removed, often as a result of cancer, and breathe through a stoma on their neck. Laryngectomees typically rely on three medical products in their everyday lives: voice prostheses, which allow them to speak; filters, which add humidification and act as a protective covering for the stoma; and housings, which provide an adhesive base for the filter to click into.

Figure 1: Before and after a total laryngectomy

MedCo was renown in the medical community for their superiorly engineered voice prostheses; in a number of countries, they also had the majority market share. In short, the company was doing well from an outside perspective. However, with patents soon expiring and new competitors emerging, MedCo was faced with increasing pressures to establish a new product portfolio that could differentiate themselves in the market in the years to come.

MedCo had a strong team in research and development, and while there were many ideas floating around, they lacked the grander perspective that could guide and drive their new innovation agenda. MedCo saw the need to shift from an engineering-driven to a customer-driven innovation process, and approached our firm to provide them with a new commercial direction using our outside-in “Sensemaking” approach. Sensemaking is a five-phase non-linear process for how our team at ReD Associates tackles business problems:

- Phase 1: Frame the problem as a phenomenon

- Phase 2: Collect the data

- Phase 3: Look for patterns

- Phase 4: Create the key insights

- Phase 5: Build the business impact

The goal of this project was two-fold: first, to develop a new commercial direction for innovation and product development based on a deep customer understanding of the phenomenon; and second, to design an overarching portfolio strategy to be carried out in the company for the next five years.

BECOMING TRUSTED ADVISORS: CLIENT UNDERSTANDING AS CORE

Our firm typically works with Fortune 500 companies that employ thousands of people. As a result, many of our projects are conducted in partnership with one business unit, such as engineering or marketing. This project with MedCo was unique for us in that it is one of the smallest companies we’ve ever worked with. However, this allowed us a larger than usual degree of immersion within the organization, where we were able to work in close collaboration with senior management, engineering, marketing, and sales teams throughout the project. The ability to work so closely with different stakeholders at MedCo allowed our team to identify the cultural and organizational barriers that could impact the success of this project, and thus the company’s future.

Before heading to the field, our team spent the first two weeks devoted to understanding the world MedCo operated in (Phase 2 of Sensemaking) by conducting an ethnography of their business. In order to deliver real impact and value for MedCo, we had to first understand how their company operated and what business problem they were trying to solve. This required their organization to be “actively and aggressively dissected, from its strategic imperatives to its financial metrics, its leverageable assets to its operational capabilities, its brand equities to its competitive landscape” (Payne, 2014). Only with a deep understanding of their business model, and what business problem was at hand, would be able to ensure our insights and recommendations were relevant to their needs and capabilities.

Using a “Five Lenses” framework to understand the client (MedCo), the industry (medical devices), people (patients and professionals), marginal practices (e.g. artificial larynxes), and emerging technology (e.g. synthetic voices), our team rigorously sifted through client and competitor reports, read patient blogs and medical books, procured treatment guidelines for laryngectomy surgery and post-surgical care, learned about changes in ordering and reimbursement policies, and identified companies using new and relevant materials.

However, understanding MedCo’s company and culture itself was equally important as understanding the world they operated in. Thus, our team spent a great deal of time at their headquarters, visiting the production site, research and development lab, and observing employees doing their job in-situ. Our observations spanned across formal meetings and workshops, as well as informal social gatherings and lunch breaks. By investing a significant amount of time at the beginning of the project into client understanding, we were able to demonstrate our level of expertise in MedCo’s business and industry, which had tremendous impact for how we built trust and authority with the company early-on.

By taking a deep dive into their world, one thing was made clear: MedCo was an introverted company that had challenges in making decisions. This insight, which had implications for the company’s future, and also for how our team decided to work with an introverted and consensus-based company, was something we’d never have been able to gather from an annual report alone. With a grasp of their company culture, we tailored our approach for working with MedCo to ensure we “consulted with care.” For example, we realized that an introverted company needed us to take more of a leadership role and to facilitate an environment where employees felt safe to speak. Because we cared for the employees and wanted them to succeed, on multiple occasions we disinvited executive management from workshops in order to create a space where employees could voice their opinion without fear of backlash. Albeit a bold move on our end, it proved to be a success as taciturn engineers began to open up and share their thoughts on what direction innovation should move in.

A month into the project, we found that something had fundamentally changed in our relationship with the client team. We had become the pivot of the company – the constant core that unified the disparate worlds of engineering, clinical affairs, marketing, and management together. Our role had evolved from outsourced help who could provide the human angle, to trusted advisors of the MedCo team. The reason we were able to evolve into this role was because we had earned MedCo’s trust on a company-wide level. Through client ethnography and rapport building, we proved we could speak the language of engineering, marketing, sales, and management, and showed that we recognized what was important to each business unit, and that we cared about the success of each.

Today, many ethnographic researchers see their job as representing the voice of the user. They prioritize gaining a deep and holistic understanding of their participants to the extent where client understanding often falls by the wayside. Although many anthropologists understand the business context of their projects, they rarely have the time, budget, or desire to also take a deep dive into the world of their clients and the industries they’re working in. But as Bezatis and anderson (2011) have discussed, “The job of ethnographers and social researchers is to act as generative intermediaries between businesses and the social world.’’ By having the same curiosity and empathy for MedCo as we did for laryngectomees, we became much more aware and sensitive to their needs, which in turn allowed us to make more valuable and strategic contributions to their business in the latter half of the project.

If we wish to elevate the standards of our praxis and to expand the role and responsibilities of our practitioners to become trusted advisors, it is imperative we prove to clients that we understand their business just as well as their users – chiefly because many of our practitioners lack the credentials, such as an MBA, that often provide immediate authority and credibility. Without a deep understanding of our clients’ business problem, strategic goals, organizational capabilities, or company culture, our ability to partake in and lead meaningful strategic engagement is impossible (Morais, 2014). Making client understanding core to our praxis is key to advancing our industry, as only then will management trust us to work with the highest levels of business decision-making.

LIFE AS A LARYNGECTOMEE

In preparing for fieldwork, our team was confronted with one big challenge: How do you conduct ethnographic research with people who can’t speak or speak well? How would we carry out six-hour long conversations without exhausting participants? What would we do if we couldn’t understand what they were saying? And how would we broach a highly stigmatized and sensitive topic – the smoker’s disease – without embarrassing or offending the people we planned to meet?

The research was conducted in four countries, Spain, US, Germany, and Sweden, with laryngectomees, caregivers, speech language pathologists, and otolaryngologists (Phase 2 of Sensemaking). Our goal was to gain a holistic and multi-faceted perspective of ‘‘good laryngectomy care’’ with an ecological research approach. Many laryngectomees we planned to meet had not yet regained their voice or had trouble voicing, and in these cases, we asked for a caregiver to be present to help translate. For those who could speak, we created a fieldwork guide centered on mapping exercises and activities that offered patients regular breaks from speaking, and also gave them the option to communicate through drawing or writing.

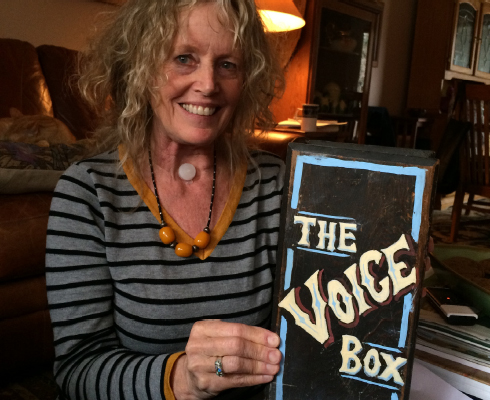

In our meetings with laryngectomees, we were surprised by how talkative and open they were. Although a sensitive area to discuss, they revealed the most intimate moments of their lives: the day they found out they had cancer, the first time they heard themselves speak with a new voice, the moment they realized they couldn’t cry or laugh anymore. We learned about their life as a laryngectomee, the social stigma they faced as a visibly recognizable cancer patient, and their daily struggles and frustrations living as a laryngectomee. As one patient told us: “I was afraid what my voice would sound like after surgery. But the biggest thing I was afraid of was losing my identity – it was to tied to my voice. I still don’t feel like it’s me when I hear my voice on the answering machine.”

Figure 2: Photo of a laryngectomee we met, Ellen, showing her new “voice box”

With healthcare professionals, we attended tumor board meetings to see how otolaryngologists decided which patients were fit for a laryngectomy procedure, observed speech language pathologists troubleshooting with patients, and accompanied surgeons around the clinic as they checked in on their patients. We even observed a total laryngectomy2 being performed in the operating room. Meeting with healthcare professionals gave us insight into the clinical definition of good laryngectomy care, which we found often went against patients’ definition of good laryngectomy care.

For example, many speech language pathologists considered patients to have “graduated from their care” once they were able to voice again. But for patients, being able to voice was not enough. They wanted to communicate with others by being able to change their pitch and volume, feminize their voice, and to express themselves through crying and laughter. As one recently laryngectomized patient told us: “I have one tone and one tone only. I am neither loud nor quiet. This is difficult for me to come to terms with because prior to surgery I had a loud booming voice. I feel like I blend in where I normally stand out.” With an ecological research approach, we were able to identify a tremendous disconnect between patients’ and professionals’ definition of success when it came to voice rehabilitation.

As many consultancies already do, we invited employees from MedCo to join us in the field. But rather than have them be passive observers, we asked them to play the part of ethnographer. For an introverted company, this was something many felt uncomfortable doing. It required them to travel to a new city, spend upwards of eight hours with laryngectomees in their homes, and watch their products being used (and often discarded) in-situ. Some had never met a “real-life” laryngectomee before, or had only met them in the controlled environments of MedCo’s campus. Thus, we saw it as our responsibility to help them better understand and gain an appreciation for the people they were creating new solutions and services for.

Prior to each session, we met with MedCo employees to go through the fieldwork guide and research practicalities. We gave them tips on how to build rapport with participants, as well as how to formulate the questions they wanted answers to (e.g. “How do competitor products compare to ours?”) in more ethnographically appropriate ways (e.g. “Can you tell me about the last time you tried another voice prosthesis?”). At the end of each session, we also gave MedCo employees the task of writing up short field notes they had to share with their colleagues. For an introverted company, these field notes played a large role in sparking conversations between people who typically work in disparate realms, and in breaking down MedCo’s silo mentality.

By having our clients play the role of ethnographer in the field, we infused them in our own Sensemaking process, helping them see laryngectomees as people with real unmet needs they could solve, rather than just as consumers. Many MedCo employees told us they felt re-energized and re-motivated about their jobs, especially those who had been there for many years, and reported that they found a new sense of purpose after joining us in the field.

Research findings from the field

Sensemaking requires the ability to lead open-ended discovery, but to be able to connect the dots to find patterns in often conflicting data (Madsbjerg and Rasmussen, 2014). From our research findings across four countries and with five different stakeholder groups, we identified many new patterns and insights (Phase 3 and 4 of Sensemaking). One key insight we found, which had profound implications for the future of MedCo’s business, was that people’s stomas come in all shapes and sizes.

The fact that people’s bodies are different is no ground-breaking insight, but the insight is magnified when it’s compared with the fact that most medical devices for laryngectomees don’t cater to this reality. Our team was confronted with the fact that housings and filters across the industry were made only to fit “perfect stomas” – perfectly flat, perfectly circular, and perfectly small. Across the participants we met, many had “imperfect stomas” and thus needed to deal with ill-fitting products that would not fully cover their stomas, which caused air leakage and made it impossible to speak. Many laryngectomees had to change their housing as frequently as eight times a day, causing a huge time-consuming burden in their daily lives. For healthcare professionals, ill-fitting products required them to repeatedly troubleshoot with patients, which cut into little time typically allocated for other speech related disease areas.

The prevailing logic in the industry was that surgeons should be educated on how to make “perfect stomas.” Thus, sales reps across the different medical devices companies were regularly sent to hospitals to demonstrate to surgeons how to make the best incision. However, the reality is that surgeons’ primary concern is removing cancer, and creating the perfect stoma falls low on their list of priorities. Because surgeons typically handover the patient’s care to speech language pathologists soon after surgery, few are even aware the impact “imperfect” stomas have on a patient’s quality of life. Our team discovered a great need for solutions that catered to the reality of patients’ bodies and stomas in order to deliver “good laryngectomy care,” not for a change in the treatment paradigm.

DIRECTING CHANGE: BUILDING THE BUSINESS IMPACT

The challenge for many of our practitioners today is that we have little room to partake in decision-making, implementation, or execution beyond the research phase. For many, our role still typically begins and ends with research: we conduct fieldwork, come up with key insights, and provide high-level recommendations. These recommendations are then handed over to management to put into action if deemed relevant. Our job has primarily been to provide the research results and inspirational ideas for our clients. However, ideas don’t mean much if we can’t marry them with implications for a company’s strategy, finances, marketing, or research and development efforts.

Being absent in the process of strategy formulation not only curtails the power and influence of our contributions (Morais, 2014), but it also has negative consequences for the businesses we work with. What we’ve seen over the years, including in our own first-hand experience with MedCo, is that businesses find it challenging to translate research findings because they are still so far-removed from their customers. As a result, senior management execute on the wrong strategic direction and continually “get people wrong.”

For example, MedCo previously conducted a quantitative survey and learned that laryngectomees are particularly concerned with the aesthetics of their filters. They interpreted this to mean that they should turn filters into a fashion accessory with bold patterns and bright colors, and subsequently hired a design agency to mock up patterns for a new generation of filters. While it is true that laryngectomees care about aesthetics, they desire filters to be as discreet as possible, and many go out of their way to camouflage it to their skin. One laryngectomee we met went as far as to paint his filters with nude nail polish each night, believing it reduced the number of people who stared at him and his stoma.

In order to help businesses truly “get people right,” the next wave of practitioners must take an active role in the writing and directing of strategy. In doing so, they can pave the way forward for management and ensure they execute the right strategic direction to drive top-line growth.

Although ethnographic research was key to the success of this project, it was used as a means to an end, not an end in itself. ‘‘Businesses in transition don’t want research or insights. They want answers, compelling ones, capable of motivating points of view and change,’’ argue Bezaitis and anderson (2011). The post-research phase is the beginning of the most critical work: building the business impact (Phase 5 of Sensemaking). For MedCo, this meant providing them with a new commercial direction and portfolio strategy to be carried out over the next five years. A commercial direction, as we define it, refers to the value proposition of a company – what the company uniquely offers to stakeholders – that can guide engineering and marketing innovation efforts. A strategy refers to a clear and concrete plan of action that delivers on the agreed-upon commercial direction.

Setting a new commercial direction for MedCo

Our insight around “imperfect stomas” led MedCo to see their business, customers, and products in a completely new light. In fact, it sparked a company-wide shift in thinking and attitude towards laryngectomy; MedCo saw a new need to design medical solutions that fit patients’ individual bodies, rather than designing one superiorly engineered product fit for all. This shift in thinking became the foundation for MedCo’s new direction for innovation, a direction concentrated on personalized solutions.

A focus on personalized solutions meant engineering products that fit the reality of patients’ bodies, which required MedCo to move away from standard mass-made products for “perfect stomas” to products tailored for diverse stoma profiles. In addition, personalized solutions meant designing products tailored to patients’ lifestyles and their various usage situations, such as for sleeping (where comfort and healing was most important), working out (where ease of air flow and strong hold was most important) and going out (where discreteness and reliability was most important), rather than focusing on engineering one filter that worked across all situations.

Our team argued that personalized solutions would allow MedCo to tackle the most important and unmet needs in the market, both for patients and professionals, by addressing the reality of “imperfect” stomas. Solutions for “imperfect stomas” would give a larger degree of confidence and control around laryngectomy care, reducing mistakes, hassles, and daily inconveniences for patients back at home and professionals working in the clinic. Personalized solutions had a strong promise to improve the quality of life for patients and professionals alike.

Establishing a new portfolio strategy for MedCo

With the ambition to deliver on personalized solutions, MedCo had to rethink its product pipeline and portfolio strategy for the next five years. However, they needed guidance in realizing this new generation of solutions. As Massot (2015) argues, many businesses need to be guided through the strategic and tactical reality required to execute on a new commercial direction. Using our knowledge and experience in the field, we identified the unmet needs of patients and professionals and translated them into a number of new growth opportunities that MedCo could potentially pursue, or as we called them: Innovation Challenges.

Innovation Challenges described a clear and concrete product or service that a) addressed a white space in the market in relation to personalized solutions, b) represented a significant business opportunity to grow the company, c) was in line with the company’s abilities and expertise, and d) was technically and logistically feasible. To ensure that these Innovation Challenges could drive MedCo’s top-line, we backed each of them with the financial implications as well as a business case for monetization. In addition to identifying new Innovation Challenges, we reviewed MedCo’s current pipeline and evaluated each of their prototypes on their ability to deliver on personalized solutions. By doing so we were able to identify the gaps and redundancies in their portfolio to create a unified portfolio strategy.

Once MedCo decided on the Innovation Challenges to pursue, we were responsible for the building and writing of an Action Plan that could turn these Innovation Challenges into internal projects to be launched in the market. In our Action Plan, we created a framework that outlined key considerations for each Challenge, for example:

- Innovation Challenge Solution Description – “What is it and what does it solve?”

- Target Group and Proposed Usage Situation – “Who and when is this relevant for?”

- Potential Marketing Claims – “What is the value proposition and its benefits?”

- Proposed Product Name – “How will we position this to customers?”

- Feasibility Based on Required Competencies – “How will we achieve this?”

- Potential Partnerships – “Who can support us in making this a reality?”

- Business Logic and Market Potential – “Where’s the money?”

- Launch Markets and Launch Sequence – “Which market do we start in?”

- Go-to-Market Initiatives – “How do we ensure uptake in each market?”

- Regulatory Considerations, e.g. reimbursements – “What are the roadblocks?”

- Key Performance Indicators – “What will this be measured on?”

- …

In building these Action Plans, we provided MedCo with an overarching portfolio strategy for its laryngectomy business for the next five years, as well as the tactical considerations required to bring these Innovation Challenges to market. As of August 2015, MedCo had registered for patents and developed multiple prototypes that arose from these Action Plans.

However, the real value of our work is in its sustained impact for MedCo’s company culture and their approach to innovation. As Cotton (2014) posits: “The promise and value of anthropology and business ultimately depends on the ability of our work to have a sustaining impact.” The framework outlined in the Action Plan would continually force MedCo to think about innovation from a customer perspective (e.g. what needs should we solve for, what are the benefits we need to deliver to customers), rather than from an engineering-perspective (e.g. what are the best materials and products) that has traditionally dominated in the company.

For our team, this project with MedCo was deemed a success because we were able to claim an active role in the writing and directing of their strategy, building the bridge between their commercial direction and their pipeline. With Sensemaking, we were able to create a red thread that connected our research to our insights, our insights to a direction, a direction to a portfolio strategy, and a portfolio strategy to a pipeline filled with real solutions for both MedCo and their customers. Our Sensemaking approach became the core foundation that defined MedCo’s business process and strategy

CONCLUSION: REDEFINING OUR VALUE PROPOSITION

As many have argued before us, ethnography is not just a research methodology, but also a way of thinking, a way of doing, what some might call a creative process. The power of ethnography is not in its methods, but in the way it can shape clients’ perceptions of people and their business in the world – as it did for MedCo’s laryngectomy business.

In order to reverse the commodification of our praxis and the “de-skilling” of our practitioners, and in turn become trusted and valuable advisors to our clients, our praxis as a collective whole must be elevated to the realm of strategy. To do so requires us to reposition ourselves and our offering. Strategy can and should be part of our professional offering and core to our value proposition.

From our own experience, we see an opportunity for anthropologists and ethnographers who have traditionally been relegated to researchers to actively take on more strategic roles. How? One approach is choosing the right companies to partner with – such as working with a small company undergoing great transition. Another approach is building authority and credibility with our clients early on through client ethnography. Positioning ourselves as experts and advisors from the beginning, rather than as researchers, can pave the way for us to partake in business decision-making when it comes to implementation and execution. Finally, one or one’s company can create a framework for how to tackle strategic business problems – such as ReD’s Sensemaking approach or Fahrenheit 212’s Magic and Money equation. At ReD, Sensemaking acts as the red thread that connects our research to our recommendations, giving our clients greater confidence and security when we advise them on their business strategy. While these three approaches do not encompass the many ways in which our practitioners can claim a role in strategy, they are tools we can begin to add to our arsenal in order to move ourselves and our offering beyond research. In doing so, anthropologists and ethnographers can play a more pivotal role for businesses and clients than they typically occupy in most cases at present.

In presenting this case study, we show the possibilities for redefining the boundaries of ethnographic praxis beyond research and into the larger realm of the overall strategic process. Our praxis can and should serve as the foundation that defines business processes and strategy, because that the evolution of anthropologist as a researcher to anthropologist as a strategy driver can literally be life-changing for people and businesses alike.

Carolyn Hou is an anthropologist and strategy consultant at ReD Associates. She has extensive experience working in healthcare, consumer goods, consumer electronics, telecommunications, and automotive industries. Hou received a Master’s in Social Anthropology from the University of Oxford. cho@redassociates.com

Mads Holme is a Senior Manager at ReD Associates. He has managed international projects on change management and organizational culture. He has extensive experience in implementing innovation programs and working in close collaboration with cross-functional client teams. mh@redassociates.com

NOTES

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank the full project team: Mikkel-Brok Kristensen, Brendan Muha, Benjamin Pape, Miro Amadeo-Hubner, and Anna Grundsten. We would also like to thank the reviewers who encouraged a great number of interesting angles for development, as well as friends and family who provided valuable contributions to early drafts. The ideas expressed in this paper are not the official views of ReD Associates or our clients.

1. For example, McKinsey recently acquired LUNAR, a design agency, in May 2015.

2. Total laryngectomies are done when cancer is advanced (e.g. T3 or T4) and the entire larynx is removed. Partial laryngectomies are done when cancer is limited to one spot (e.g. T1 or T2) and only the area with the tumor is removed. Patients who undergo partial laryngectomies are often able to retain their natural voices.

REFERENCES CITED

anderson, ken

2009 Ethnographic Research: A Key to Strategy. Harvard Business Review 87(3): 3:24

Baba, Marietta L.

2014 De-Anthropologizing Ethnography: A Historical Perspective on the Commodification of Ethnography as a Business Service. In Handbook of Anthropology in Business. Rita Denny and Patricia Sunderland. Pp. 43-68. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press

Bezaitis, Maria and ken anderson

2011 Flux: Changing Social Values and their Value for Business. Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings 2011:12-18

Cefkin, Melissa, ed.

2009 Ethnography and the Corporate Encounter: Reflections on Research in and of Corporations. New York: Berghahn Books

Cotton, Martha

2014 The Sustaining Impact of Anthropology in Business: The “Shelf Life” of Data. In Handbook of Anthropology in Business. Rita Denny and Patricia Sunderland. Pp. 571-585. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press

Gebhardt, Gary F.

2015 Yes, Virginia, We ‘‘Do Ethnography’’ in Business Schools. Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Website. Accessed August 16th, 2015

Hasbrouck, Jay

2015 Beyond the Toolbox: What Ethnographic Thinking Can Offer in a Shifting Marketplace. Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Website. Accessed August 16th, 2015

Jordan, Ann T.

2010 The Importance of Business Anthropology: It’s Unique Contributions. International Journal of Business Anthropology Vol. 1(1): 15-25

Lombardi, Gerald

2009 The De-Skilling of Ethnographic Labor: Signs of an Emerging Predicament. Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings 2009:41-49

Mack, Alexandra, and Susan Squires

2011 Evolving Ethnographic Practitioners and Their Impact on Ethnographic Praxis. Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings 2011:18–26

Madsbjerg, Christian and Mikkel Rasmussen

2014 The Moment of Clarity: Using the Human Sciences to Solve Your Biggest Business Problems. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press

Massot, Chris

2015 Bridging the Gap between Ethnographic Praxis and Business. Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Website. Accessed September 8th, 2015

Morais, Robert J. and Timothy de Waal Malefyt

2010 How Anthropologists Can Succeed in Business: Mediating Multiple Worlds of Inquiry. International Journal of Business Anthropology Vol. 1(1): 45-56

Morais, Robert J.

2014 In Pursuit of Strategy: Anthropologists in Advertising. In Handbook of Anthropology in Business. Rita Denny and Patricia Sunderland. Pp. 571-585. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press

Payne, Mark

2014 How to Kill a Unicorn: How the World’s Hottest Innovation Factory Builds Bold Ideas That Make It to Market. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing

Squires, Susan, and Christina Wasson and Ann Jordan

2014 Training the Next Generation: Business Anthropology at the University of North Texas. In Handbook of Anthropology in Business. Rita Denny and Patricia Sunderland. Pp. 346-361. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press

Sunderland, Patricia and Rita Denny

2013 Opinions: Ethnographic Methods in the Study of Business. Journal of Business Anthropology 2(2): 133-167