Ethnographers operating in the future-focused context of business consultancy face a core challenge. Our approach is holistic and human-centric, “based on the researcher sharing time and space with the people he or she wants to understand, establishing relationships with them and thereby experiencing life from their perspective” (Kirsten Hastrup et.al: Ind i verden, 2010). Our clients want to stay relevant in the future. They want us to predict future behaviours, aspirations and dreams; to demonstrate what will change, what will disrupt and how people will be different.

We’re often confronted with the perception that ethnography is a toolkit limited to exploring present worlds, and therefore holding limited value to futures work and business strategies.

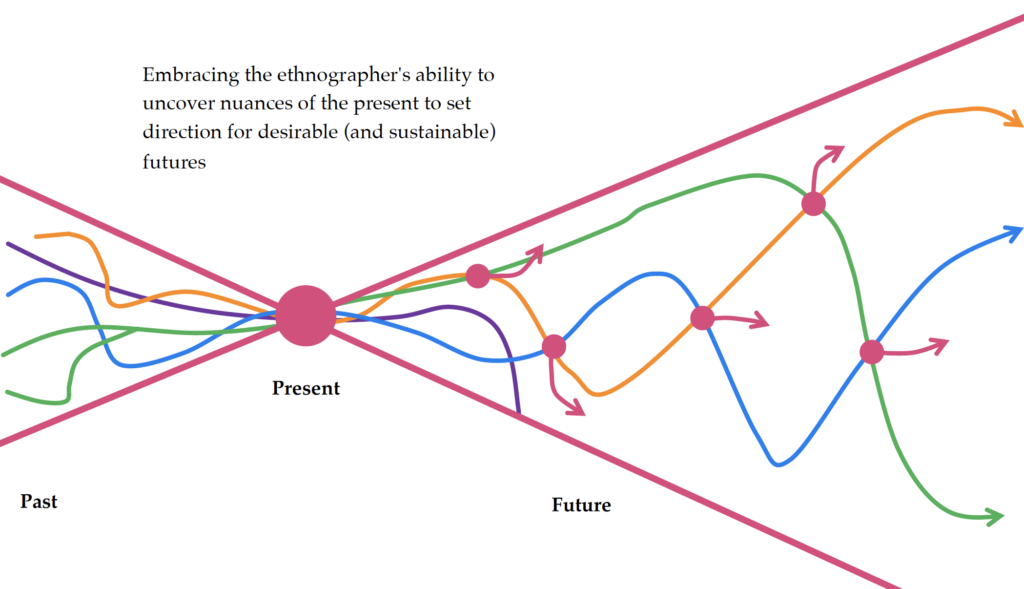

This notion relies on a somewhat sci-fi view of the future as something disconnected from the now. As something which is either already happening, ready to be uncovered, or moldable, for us to design, free of current realities. But it is neither. “The future” is always plural; it is technological enablers for new products and services, it is a projection of current narratives and discourses, and it is unpredictable pandemics, natural catastrophes and conflicts. Across all of it, the starting point is the present.

How can we help each other, our clients and our colleagues expand the perception of the ‘nature of change’ and explore the contextual space of the present, identify connections and potential in what is all around?

Looking ahead? Look around! Identify and invest in the values most likely not to change

Before Nicolaus Kopernikus came around, we all believed the earth to be at the centre of the solar system. It seemed obvious, and Kopernikus was highly unpopular for suggesting that this might not be the case.

We often use the analogy of the solar system to start a conversation with clients about the value of ethnography. We challenge companies to shift their perspective when looking at the role they play in relation to their users, customers, or consumers. If they accept that their products and services are not at the centre of the universe, and put the user/consumer – the human – at the centre instead, they shift from a focus on the business problem, to the human problem, of which the business problem is merely a symptom.

This shift also implies a new perspective on time. Business problems are often related to time in a very linear way – what are we up to today, what are our strategies going forward? Understanding and acting on human problems requires a different contextual understanding. They are related to the different spatial dimensions of our everyday worlds; our social, cultural and structural surroundings.

But doesn’t it seem obvious that we should design for the future? Who would want to be so narrow-minded, not looking ahead? What we suggest is that looking ahead can be more conservative than looking around. And that designing for what is valuable to humans today is less of a risk than designing for the future, based on our limited imagination of it.

In an uncertain world, the safer bet is to explore, identify and invest in what will most likely not change. Innovation is crucial to long-term success in any industry, but predicting the future is impossible. Recognising this, and rooting your strategy in persistent truths is a powerful approach.

Innovation potential lies in the ability to identify what values will persist, and how to hold on to value in the customer relationship when setting off to achieve new business goals.

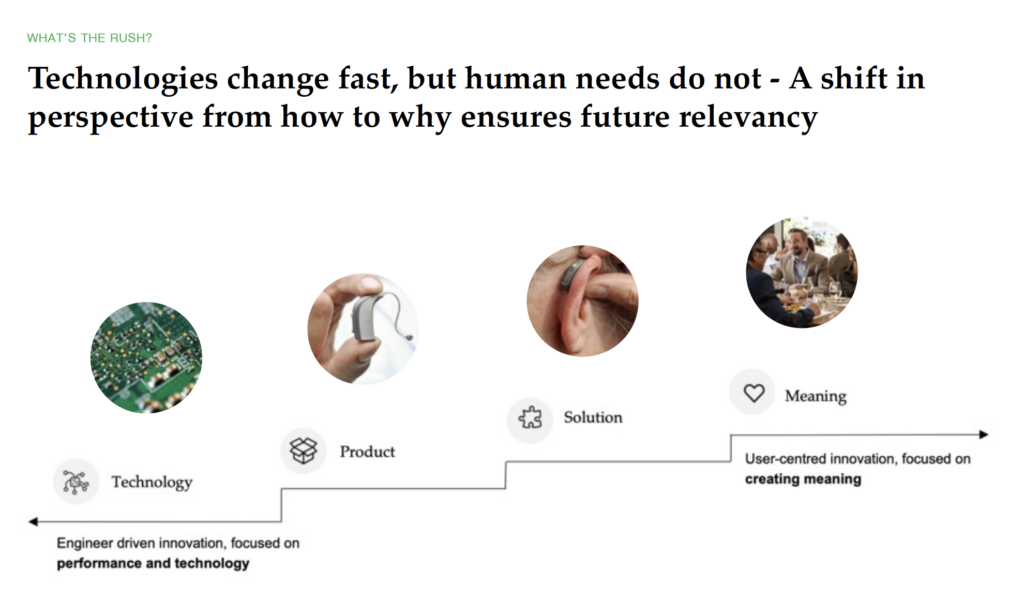

What’s the rush? Technologies might change fast, but human needs do not

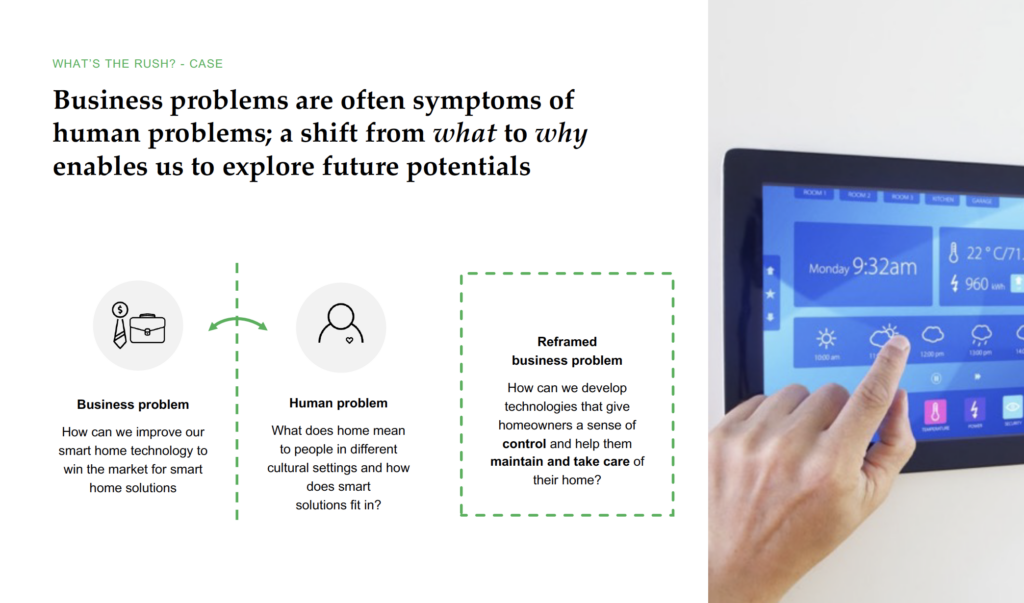

Innovation is not just about seeing what is new, but seeing what is already there in new ways. The ethnographer can act as the “alignment expert” between engineering imaginations and human realities. We have an ongoing partnership with a global window manufacturing brand; a company with an engineering mindset that, over the years, has made an ambitious effort to become increasingly customer centric. A few years back, we collaborated on a project assessing the digital innovation potential for the company in entering the smart home market.

Smart home technologies have gained popularity both as exciting entertainment and through the promise of frictionless automation, and as an attempt to tap into the trend, the company had launched smart products across markets. However, the products did not perform well. In other words, they experienced a clash between an emerging trend and a consumer response, which did not seem to make sense.

The company engineers were very curious to learn which method of handling a window in the future might be preferred over another. In order to answer the question from the brief, we wanted to explore the meanings and practices of homemaking—not in the future, but right now. We spent time with people in their homes to understand their routines, worries and responsibilities.

Through a deep understanding of windows as a part of homemaking, we discovered two important needs that the operation of windows meets in the home: (1) control and (2) care and maintenance. What we discovered was that both expectations and experiences of smart technology were linked to a reduced sense of control. Moreover, the members of the household responsible for care and maintenance activities were generally not those responsible for investments in new smart technologies.

The ethnographic approach helped us shift the client from an engineering problem—“how do I operate a smart window”—to a human problem—“how do I maintain a sense of control in my home?” We also shifted the perspective from a linear processual focus on “how” people would operate their windows, to “why” people open their windows. The depth of the insights provided the engineers and product developers with a strategic direction for future development of new solutions to support home owners’ needs related to windows, home and homemaking.

This case presents an example of the dynamic between change and continuity. As we discovered here, as well as in many other cases, technologies might change fast, but human needs do not necessarily. In other words, the future we can imagine, in engineering and technological terms, is not necessarily the future which is desirable to live in. This does not imply that change and innovation are irrelevant. Rather, change is everywhere, and the ethnographer offers a careful perspective on what has changed, what stays the same, and which changes are deliberate and which should be avoided.

Stay in the trouble! Embracing the nuances of the present to set the direction for desirable (and sustainable) futures

Our argument is somewhat provocative, that focusing on the future could be more conservative than being curious about the present. The notion that the future is something out there for us to predict and await, limits our creativity and in the end, our ability to act, to define and enable the futures we can imagine and desire. Perceiving futures as something detached from the present makes it conveniently easy to push the troubles ahead of us; we see it as something abstract which never really hits the fan.

Donna Haraway, the American professor Emerita at the History of Consciousness Department at the University of California, Santa Cruz, argues that we, as humans wanting to shape sustainable futures, have to “stay with the trouble”:

“To me, it seems obvious, that we must learn to stay with the trouble…We cannot control the future, and we cannot come up with big solutions from a position in the future. The big solutions are the wrong way to go about it. Elon Musk who wants to create life on other planets, and Bill Gates, who talks about the big technological solutions, have exposed how the old progressive dream about new worlds is desperate and denying the reality. Instead, we need to work together to repair the damages, and create a vision of a present and a future which is still possible. Forget about the big futures. Let’s stay in the trouble. The person who stays in the trouble does not look away, or up, but explores the surroundings and lives with them”.

Haraway’s words resonate with ethnographic thinking and it rings true to us as human-centred innovation consultants. Frequently the human-centred approach is discussed in opposition to what we might call the planet-centric approach. But from our point of view, these are not opposites. Humans shape our world in massive (and potentially catastrophic) ways; therefore, we need to understand humans to drive change.

The ethnographic approach is a tool for staying in the trouble. It prompts us to embed ourselves in the mess of the present. And with this as the starting point, we can explore, identify and enable desirable change towards sustainable futures.

A framework for ethnography and futures work

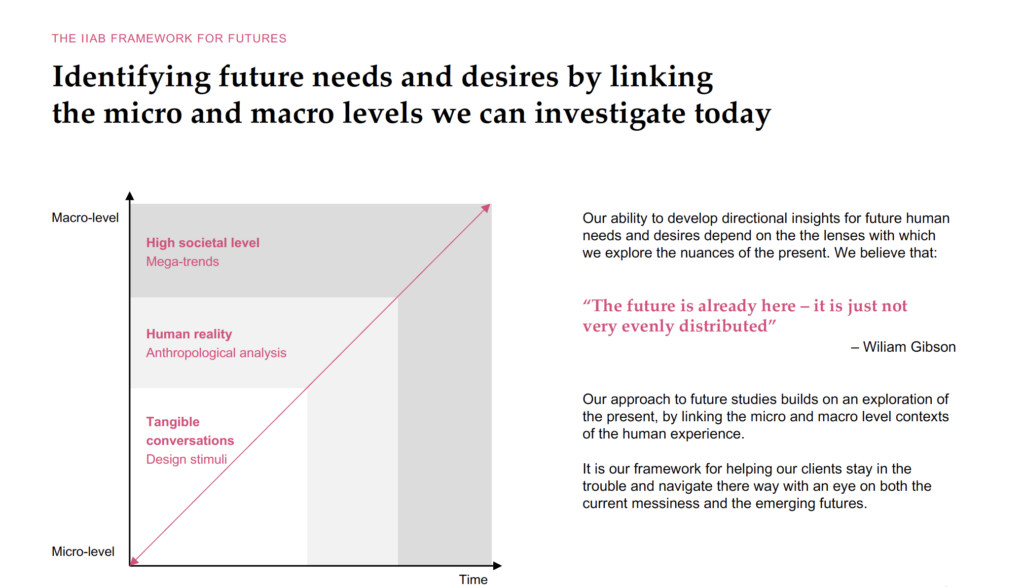

At IS IT A BIRD, we have developed an operational framework for applying ethnography to futures studies. The framework is our take on how to operationalize a holistic approach to futures, and also break it down without pulling it apart.

One of the key elements of the framework is the need to connect the micro and the macro level, the I-frame and the S-frame as some might prefer to call it, and acknowledge the dynamics between people and objects, people and people, and people, structural environments and discourses.

A second element is not to detach the micro and macro level of human behaviour and not to limit findings to present conditions. We distinguish between them, not to divide them analytically, but to be able to see each layer, as we peel them off in our research. We need to zoom in on the specifics to identify the universal, and we need to stand still and be present in order to see how things are moving and connected around us.

In our research design, we aim to link the micro and the macro levels of change and facilitate a conversation between them. The framework enables us to facilitate tangible conversations without missing out on the bigger picture. Zooming in and dwelling on the details and zooming back out to see how the dots are connected.

In this dynamic, we see the value of the ethnographer’s role as the “alignment expert” between technological future fantasies and human realities. In this time-spatial context, the ethnographic approach aligns, compares and connects the potential for change at the micro and macro level. The ethnographer detects the connections and relationships between moving parts in the present across the tangible and the abstract. It helps to operationalize what is otherwise abstract, and define principles and guiding insights to what is specific.

The flexible, creative mode of the ethnographic approach enables action. Instead of waiting until we have figured it all out, the ethnographic approach prompts us to explore and experiment, and to be flexible in our interactions with our surrounding worlds. Or as Tjørnhøj Thomsen puts is: “.. (be) open, flexible and grasp the unexpected.” (Kirsten Hastrup et.al: Ind i verden, 2010)

We want to end where we started: the solar system. The ultimate trouble which we are all in, you might say. Instead of looking out toward the meteors which might hit, we should look down, at the soil burning beneath our feet; and when thinking about the nature of change, remember that we have a role to play in this picture. The future is something we can actually influence, if we are curious enough to understand how it is emerging around us and decide on how we want to drive positive change.

As late anthropologist David Graeber, poetically states: “The ultimate, hidden truth of the world is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently.”

IS IT A BIRD is an EPIC2022 Sponsor. Sponsor support enables our unique annual conference program that is curated by independent committees and invites diverse, critical perspectives.

References

Halse, Joakim (2014), Ethnographies of the Possible: The Temporality of Design. In Design Anthropology: Theory and Practice. Ed. Wendy Gunn, Ton Otto & Rachel Charlotte Smith. Bloomsbury.

Haraway, Donna (2016), Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press. 2016.

Mead, G. H. (2002 [1932]) The Philosophy of the Present. Prometheus Books.

Montuori, Alfonso (2003), The Complexity of Improvisation and the Improvisation of Complexity: Social Science, Art and Creativity. Human Relations 56:2.

Pink, Sarah et. Al, ( 2017), Anthropologies and Futures: Setting the Agenda. In Researching Emerging and Uncertain Worlds. Bloomsbury.

Rabinow, P., & Marcus, G. E. (2008) Designs for an Anthropology of the Contemporary, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Related

EPIC Summit: What’s Next versus What’s Valuable: Ethnography in a Future-Focused World

0 Comments