Cast Study—This case explores a business strategy development project run by Stripe Partners for a London-based online healthcare company, Dr Ed. The first part lays out the details of the process: an intense four-day ethnographic research programme called the ‘Studio’ involving the Dr Ed senior management team. The second half reflects on the outcomes of the process one year on through a series of management interviews, and evaluates the contribution the Studio made in relation to the new business strategy. The evidence from the case suggests that the concept of strategy can be reappraised. From strategy as a static set of choices made at a specific point in time to strategy as an unfolding network of people, shared experiences and artefacts that is constantly being remade. The primary benefit of the Studio approach is its capacity to initiate, align and catalyse a ‘strategy network’. Studios are effective because they combine ethnographic encounters with collective problem solving to produce rich, tacit forms of knowledge that engender shared commitment and understanding.

INTRODUCTION

Business Context

Dr Ed is an ‘online doctor’ service. Formed in 2011, their primary business is providing people across Europe (UK, Germany, France, Ireland, Austria and Switzerland) with simple access to common prescription medicines (such as erectile dysfunction medicine, contraceptive pills and asthma medication).

Dr Ed operates in an expanding market, the result of legislative changes across the EU which have enabled the remote prescription of specific medicines. Awareness levels of the service remain low, and to date customer acquisition has been driven by paid-for and organic online search. In the UK a number of well-known incumbents have used their brands to differentiate themselves online from new market entrants like Dr Ed. As the market has matured in the last few years customers have become increasingly price driven, accelerating the commoditisation of the market.

Amit Khutti, Managing Director and co-founder of Dr Ed, approached Stripe Partners in early 2015. He explained their situation: a successful business with ambitious growth plans coupled with high levels of industry knowledge, but an uncertainty on where to commit their energy and resources for the next phase of growth. An external consultant had helped the management team develop six potential strategic directions for the business, but they were unclear which represented the best opportunity.

Beyond sales and survey data, the management team had a limited understanding of their customers. The Managing Director felt that understanding more about their customers would help them set the right direction for the business. His brief to Stripe Partners was simple “bring my team closer to our customers and in doing so help us develop a 3-year business and innovation strategy”

This case study lays out the subsequent ethnographic research process Stripe Partners facilitated and explores the impact it had on the Dr Ed business in the year since the engagement.

Background to Stripe Partner’s Approach

Stripe Partners is a ‘global strategy and insight’ consultancy that specialises in ethnographic research. Since 2013 Stripe Partners has worked across a wide range of clients and sectors, encompassing brand, product and business strategy briefs. The guiding principle of Stripe Partners’ approach is one of pragmatism: retain and develop practices that result in significant client impact, and phase out others. As patterns have emerged across projects we have synthesised our experience into a coherent approach termed ‘The Studio’.

The Studio is characterised by three core features. First, it emphasises first hand client engagement in ethnographic research. Second, it encourages multidisciplinary groups to live with one another over an extended period in the field to the exclusion of all other work. Third, it privileges focused, goal-oriented, iterative, team-based activity.

The Studio approach has produced noteworthy results, including producing P&G’s ‘lowest cost per impression’ advertising campaign in history. But, until now, there has been limited analysis into how and why it works. In a paper for EPIC 2015 we explored the philosophical underpinnings of the Studio approach (Roberts and Hoy 2015). Despite the fact that the paper included an illustrative example from a project, it did not attempt to explain the underlying mechanisms that make it a successful approach to solving commercial strategy challenges.

The purpose of this paper is to explore how and why the Studio approach creates impact by exploring a particular case. The first half of the paper is descriptive. It introduces the business background and provides an overview of the Studio activity. The second half is analytical. In it we reflect on the outcomes one year on. From interviews with the Dr Ed team we outline the underlying mechanics of the process. The case study therefore represents a specific example of how and why ethnographic work conducted through a studio approach creates impact and value. However, we also argue for the more general applicability of the studio approach to strategic business challenges.

PART ONE: THE DR ED GROWTH STUDIO

Meet the Participants

The Dr Ed management team is diverse with a variety of backgrounds and skills. Amit is an ex-McKinsey & Co consultant and formerly Strategy and Planning Director in a major NHS hospital trust. David, Amit’s co-founder, has a background in Law. Louisa, the Medical Director, is a qualified Doctor. James D, Head of Operations, is a trained Pharmacist. Joe, Chief Marketing Officer, worked previously at another online healthcare start-up. Anita, Director of Product, has a background in technology and software development. James P, Marketing Manager, an experience digital marketer.

Studio participants from Dr Ed and Stripe Partners

Each participant entered the Studio with a unique perspective and set of priorities, which flowed naturally from their backgrounds and roles. A number of strategic directions had been discussed prior to the Studio each had specific advocates across this team.

The Stripe Partners Studio team included two Partners: Simon Roberts and Tom Hoy, and two consultants, Charlotte Hollands and Kat MacDonald-Taylor.

How the Process Worked

To date the management team had had very limited direct exposure to their thousands of daily users. Together with Stripe Partners, Dr Ed identified three user types which were important segments for the business: repeat prescribers of (1) asthma inhalers (2) medication for erectile dysfunction and (3) contraceptive pills. The management team believed that by understanding these core users they would be able to define the future strategic direction of the business.

Given the sensitive subject matter and limited database, Stripe Partners consultants personally called regular Dr Ed users to ask if they would be willing to become part of the research, and host up to three people at home. This process was time consuming, but a worthwhile way of establishing contact.

Meanwhile Stripe Partners rented a large apartment in Angel, North London, which would act as the HQ for the duration of the project. Stripe Partners selected the space because it could comfortably accommodate four simultaneous workshop sessions as the group would be working in small teams.

A Studio team discussing the morning’s research

Stripe Partners prepared a fieldbook for each Studio participant, which included a detailed outline of the schedule, tips and tricks for conducting fieldwork, along with space to note down observations. Alongside this we developed a detailed fieldwork guide for each team leader.

The Dr Ed Studio fieldbook

Finally, Stripe Partners set-up a WhatsApp group which would serve as an ongoing space to share observations and experiences as teams dispersed on their fieldwork assignments each day.

Sharing experiences across teams on the WhatsApp group

The first three days of the Studio followed the same structure. The group split into four teams of three (two Dr Ed representatives and one Stripe Partners team leader). First, each team travelled together to a patient’s home and spent three hours exploring their world – including, but not limited to, their family history, medical condition, healthcare interactions and use of the Dr Ed service. The Stripe Partners consultant led each research encounter, with Dr Ed representatives given clear roles to fulfil such as capturing images and video, or probing specific areas of interest.

Discussing product choices with a user

Second, each team spent the early afternoon pursuing a ‘mission’ that would shed further light on the user’s experience (for example, to get insight into the benefits of using the online service Stripe Partners briefed participants to attempt to register at local doctor’s office / surgery).

Joe embarks on a research mission

Third, each team returned home and spent two hours discussing and capturing their key observations from the morning’s research and mission, facilitated by their Stripe Partners team leader.

A team ‘download’ session post-fieldwork

Fourth, the four teams gathered together to present and discuss their day’s research. As a group, we then developed shared insights and initial implications for the business and its three-year strategy.

On the second night Stripe Partners hosted a dinner at the apartment where the group was joined by two executives from an online financial services business. The executives discussed with Dr Ed the parallels of operating as a disruptive business in a highly regulated environment and how they had put customer research at the heart of their business’ operations.

Expert dinner with Nutmeg, an online personal finance business

On the fourth and final day the group used the insights from the previous three days to develop the three-year strategy. Participants started by developing the high level mission and vision for the business. Then we worked in teams to consider the implications for different functional areas of the business and to develop concrete actions plans.

Discussing the three-year strategy at the final debrief session

PART TWO: EXPLORING THE OUTCOMES

It’s common at the end of an intensive strategy development process to create ambitious plans in the moment, only for the plans to dissipate as the reality of everyday business takes hold again. One year on we revisited Dr Ed and interviewed Amit, Louisa and James P to understand where the business was now, what impact the Studio approach had achieved, and to explore why.

The following section discusses the outcomes as they were reported in the interviews, and in doing so lays out a theory for how they were produced. The analysis seeks to ‘trace the associations’ (Latour, 2007) that were forged at the Studio in order to go beyond a linear understanding of how impact was created. To anticipate our argument, we suggest that rather than seeing business strategy as a set of static directives, it should instead be understood as an unfolding network of associations.

The Privileging of ‘Hard’ Outputs

One of the first questions to each of the interviewees was the same: “What’s changed in the last year as a result of the Studio?” All three interviewees were confident that the Studio had made a significant impact on the business. This impact was initially framed in terms of tangible, hard decisions and results:

“We’ve distilled down the core strategy we developed in the Studio – the mission, vision and the four planks of our strategy”

“It’s driving commercial value, although in only a year I don’t know if it has dropped to the bottom line”

“We’re implementing a new delivery service that will enable people to pick stuff up from 200 stores”

“We’ve become more focussed on actionable insights in digital marketing – using the jobs to be done framework”

The most clear-cut result had been the renaming and rebranding of Dr Ed. Entirely new websites and a new brand identity are currently being rolled out: “we’re in the process of relaunching all the websites – reflecting the trust and legitimacy needs [we identified in the Studio]”

The company rebrand is a major undertaking which involves teams from across Dr Ed and the dedication of significant resources. Amit was clear that he felt the company would not have undertaken such a significant step without going through the Studio experience.

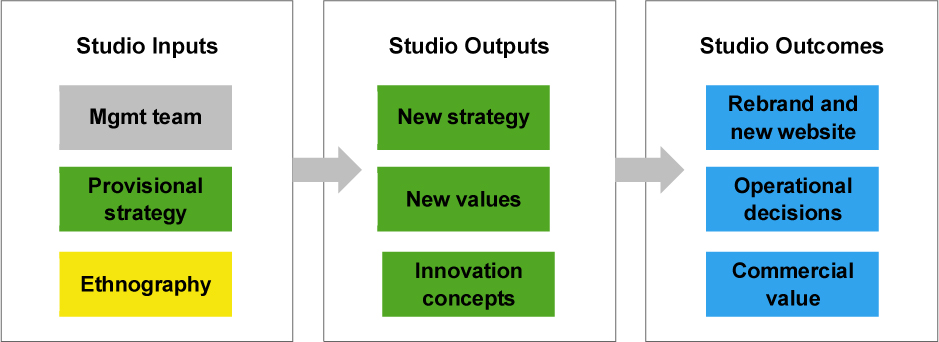

When impact was first discussed in the interviews, a linear story was told of a clear set of inputs resulting in a clear, definable set of outcomes. The inputs included the existing hypothesis about what the strategy should be, combined with the ethnographic research. The key output of the Studio was the new strategy; a set of directives as defined in the Studio. The outcomes were then framed as the product of these directives.

The initial, linear story of impact

However, the causal links of some of these claims were not immediately clear. While many of the changes our interviewees pointed to had been outlined in the final Studio workshop session, these ideas had been initial, and sat alongside many other ideas that hadn’t become reality.

Equally noteworthy was the fact that the interviewees made links between the Studio and specific initiatives that hadn’t been discussed during the Studio. These were often tactical shifts, from a change to the way management meetings were run, through to sending team members out to conduct ethnography themselves. Nonetheless, they were attributed to the Studio process. As Louisa, Medical Director, put it: “I honestly think that countless things have changed because of the work with you…the whole way we think about what we do is different”

Viewing the Studio through the lens of a traditional innovation process, these claims could be discounted as loose, abstract or at best the products of happenstance. When reviewing the tangible outputs of the studio and outcomes described, it is hard to make case that one led in a straightforward way to the other. The paper trail didn’t add up. However, our interviewees were insistent about the impact. It seemed there was a deeper dynamic at play. Further exploration revealed aspects of the Studio process that helped to explain the associations and connections the interviewees were making.

Highlighting the Role of Tacit Knowledge

Reading Amit, Louisa and James’ comments again it is noteworthy how they represent the significant outcomes of the Studio. The language they deploy disassociates themselves from the changes they describe. The strategy documents, patient posters and other tangible outputs become agents that, once committed to paper, carry forth the value of the Studio into the wider business.

The follow-up interviews with the team revealed that it was not just the documentation that was making the impact. For example, in the weeks following the Studio the management team shared user stories and insights with the wider business. Stripe Partners designed user profiles for this purpose, but the meetings themselves failed to inspire the team to take action: “we presented to people every Wednesday afternoon where we talked them through…some people didn’t find it powerful…how it was presented was a problem.”

All three interviewees noted that, when sharing patient insights from the Studio with the wider business, it was difficult to truly convey the content and meaning of their experiences. In fact, there was anxiety that talking about the research directly could alienate an audience who had not shared in the underlying experience. Louisa commented that “I bring it up a lot [with the other doctors] – maybe too often. To the point they get annoyed with me.”

These frustrations highlight the distinction between explicit and tacit knowledge. As Michael Polanyi famously observed “we know more than we can tell” (Polanyi, 2009). Studio participants were struggling to share the richness of their personal insight because much of the nuance is inexpressible, contingent on set of underlying first hand experiences to which those who had not participated in the Studio could not relate.

It appeared it was not just the formal ‘outputs’ of the Studio that were driving change across the business. The formalised user profiles, vision and strategy documents were useful reference points, but in practice it was the Studio participants themselves who were acting out and acting upon the learnings from their shared experiences.

The evidence here somewhat repudiates the work of Nonaka and Takeuchi, who popularised the idea of tacit knowledge in business contexts (1995). They argued that breakthrough insights are acquired through first-hand experience, a hypothesis that participation in the Studio process seems to support. But their second claim, that tacit knowledge can be made explicit through metaphor, codified, and then internalised by the wider organisation (the ‘knowledge spiral’), is not clearly supported by the case of the Dr Ed studio.

The interviews demonstrate that the tacit knowledge acquired was not simply transformed into metaphor and then integrated into an organisational ‘knowledge spiral’. Rather it has been manifested in the everyday actions and practices of participants who embody this new perspective. It is the consequence of these embodied actions, not the codified outputs nor the symbolic transfer of knowledge to non-participants that was instigating change. Louisa described her embodiment of the outputs quite literally, “everything from a marketing campaign to how I speak to a patient on the phone…my tone of voice… that’s based on what we know our brand now is”

Although elegant, Nonaka and Takeuchi account of tacit knowledge seems inadequate in explaining the richness and complexity of the knowledge acquired, and therefore oversimplifies both its translation and application.

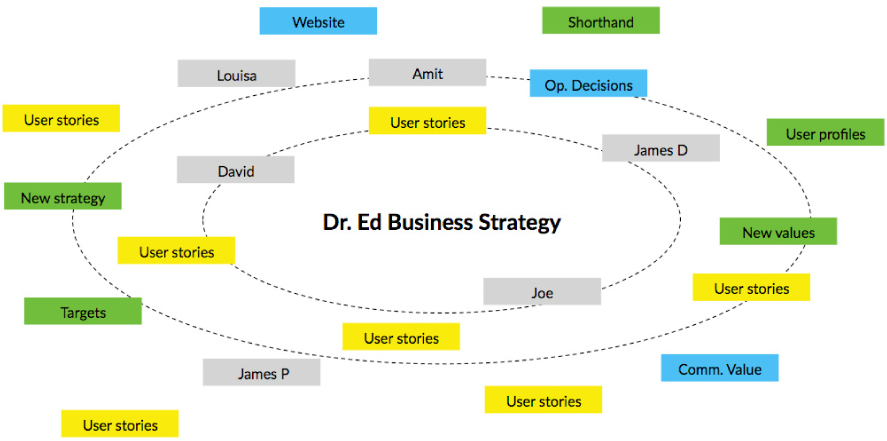

Situating tacit knowledge in a network of associations

If we think about Dr Ed’s emergent business strategy as “a web of relations that makes and remakes its components” (Law 2007), then a more nuanced analysis begins to emerge.

The Studio instigated this ‘web of relations’ by arranging a set of actors around a particular challenge or problematization (Callon 1986) – namely the need to create a three-year strategy. The nature of these actors is diverse: some are people, some are written artefacts, some are shared stories from the ethnographic encounters. The important point is that they only make sense in relation to one another. Seen in this context, the project outcomes are a product of this network of associations reproducing and amplifying themselves over time (rather than the product of a simple linear process of strategy development, formalisation and execution).

The network – let’s call it Dr Ed’s Business Strategy – has produced long-term value because it remakes itself beyond the environment of the Studio. Each participant returned to their specific part of the business (be it medical, pharmaceutical, marketing or strategy) and made everyday decisions informed by this shared underlying network of associations forged at the Studio.

One example that draws out the distinction between this emerging concept of ‘strategy as a network’ as opposed to ‘strategy as a document’ is Dr Ed’s shifting approach to customer delivery. The ethnographic research revealed the complexities of delivering sensitive products to the home. One customer declared that he wanted Dr Ed to become known as the ‘Uber of healthcare’ and make access to these products truly discrete and seamless.

At this point, the Nonaka and Takeuchi would suggest our job as researchers is complete: we have identified our metaphor. Dr Ed is the ‘Uber of healthcare’. This is the idea that will convince our client of the importance of getting delivery right. But as we will see in the next part of the story, metaphor is not enough. People need to see the complexities first hand in order to grasp the nuance and become committed enough to truly make change happen.

Initiating the Network

Viewed through the prism of ‘strategy as a network’ rather than ‘strategy as a document’, the role of the Studio becomes clearer. It is effective because it successfully initiates, aligns and organises a new network of associations. In this sense the Studio plays the same role as the researchers who corralled the scallops, scientists and fisherman in Callon’s famous study of scallop fishing in France (1986). How did the Studio initiate, align and catalyse the network? The interviews with the participants revealed several different dynamics at play.

a. The creation of a private, shared language to describe the network

Louisa felt that the intensive, team-based approach of the Studio helped to produce insights and other knowledge artefacts collectively.

“Moving from intensive info gathering, to [eating] lunch and other challenges, and then an afternoon of really reflective, contemplative…to me it was a brilliant way to work because you got stuck in and then came back and share…it felt like a really special sharing time – the patients talked about how they felt too…because you take on their emotions”

It seemed that the regular rhythms of each day, with in-depth team-based research followed by reflection, sharing and implication building, had created a corpus of language, stories and artefacts imbued with a meaning that only Studio participants truly shared.

“[By] experiencing it first hand and then talking about it together…you create stories, you create shorthand, you create shared language, you create ideas that are linked to something that you’ve just done, to real people and physical things”

The ‘shorthand’ that Amit describes is embedded in the language of everyday business a year on. Now when the management team discuss a plank of the strategy or a value, it does not exist independently at an abstract level, but provides an instant shortcut to a rich, concrete network of shared associations and meanings from the Studio. Louisa puts it like this:

“We don’t talk specifics but when we mention a value we know it’s there because of the time we had together… there’s a feeling there’s concrete research and experiences that back up what we do everyday”

In this sense the Studio network is remade everyday by Dr Ed. Ongoing interactions between the network mean that the shared reference points are reapplied to new situations as they arise. The textured understanding of participants enables them to authentically recreate the network over time, in a way that is mutually coherent. By contrast if Dr Ed had taken a ‘strategy as document’ approach this more static form of knowledge would have become detached from changing circumstances, open to a wider range of interpretations and therefore outcomes.

b. The practice of immersive team-based ethnography promoted empathy

It was not just meeting customers, but working in a structured way, facilitated by expert researchers, that produced a deeper, anchored set of insights and implications that had the power to endure.

“Your role was important because you helped us turn things concrete… otherwise we would have just said ‘that felt good, that felt fun’ – we needed people to steer the session…to pull it into something concrete”

The compressed, guided process also helped to keep the team on task, cocooned from the interruptions and staccato rhythms of everyday life in the office. They felt that this distancing from the office and immersion in their customers’ worlds enabled them to arrive somewhere new as a team.

“The compression is important – you’re relating it back to the company but you’re not thinking about your day job – the spreadsheet you need to complete…you’re not distracted…you can get to clarity…you pack a lot in and you get somewhere…you’d process it less if you did and then left it, did it and then left it…you wouldn’t absorb it…you wouldn’t spend time to work it into something useful for you (personally)”

There is also a sense that this intensive experience increased empathy across the team. By conducting ethnographic work together, the data becomes a point of shared connection. The team was able to understand how their different personal perspectives and their functional roles were shaping their own, and each other’s, responses to their research experiences.

“Before a marketing team would have pushed their agenda, now they understand the importance of the clinical side…everything is now more infused with responsibility”

Over the course of the Studio the group met with just twelve Dr Ed customers. One of the anxieties the management team had about the approach was this sample was too small. How could you build a new strategy on such a small sample size? But on reflection the team agreed that it was more compelling to speak directly with a few people, rather than commission an agency to research twice as many independently. As Louisa commented, “if you talk to one person and what they say is powerful, you have to listen to it…in that sense a small number is never irrelevant.”

c. The embodied, emotional understanding acquired through the research

Interestingly the word ‘emotion’ featured heavily in each of the interviews. There was something particular about the process, about confronting customers directly, that differentiated the understanding they had acquired from more static forms of information and knowledge acquisition. Amit contrasted the emotional understanding he had gained through the Studio with customer insight that had been presented second-hand:

“[a supplier] shared some customer segments… they say ‘hey this is Jane, she’s the typical 35-year-old woman, who has two kids, and shops here, and blah…and you’re like I don’t remember Jane, or really care about Jane…it feels two dimensional, it is two dimensional… in these companies when they say ‘what does Jane think?’ but they don’t really know…it’s just a couple of bullet points…it’s abstract… when I think of my asthma guy, I really feel it, it’s more of an emotion”

By contrasting the ‘bullet points’ of the segmentation with the ‘feel’ acquired through the Studio, Amit is distinguishing between propositional knowledge and embodied understanding (see Roberts and Hoy, 2015). While Amit only actually met three customers face-to-face over the course of the Studio, these encounters, and those shared by other Studio teams in-situ, helped participants develop a textured ‘feel’ for their customer’s world. Importantly, because their experience is multidimensional, this feel is “sticky” and can flex and adapt to new (business) situations as they emerge. The bullet points, on the other hand, exist in a relative vacuum and can only be interpreted literally and, therefore, narrowly to the environment they initially addressed. For Amit and other members of the team, the customers they met become touchstones to which they could continue to return to draw inspiration and guidance as circumstances changed.

d. The commitment generated by the experience

Another important aspect of Amit’s observations is revealed by the word ‘care’. When it comes to making change happen within organisations, truly caring can be the difference between starting an initiative and finishing it. Bullet points did not motivate Amit to put himself on the line in the way that the Studio process did. For example, lets return to the complex change the company is undergoing to improve customer deliveries:

“[the experience] made it feel real – I now know that delivery wasn’t just important but really important. And more complicated than we thought. It’s so contextual how people think about delivery…we saw when we got it right people really loved it”

In making the distinction between information and knowledge Nonaka and Takeuchi highlight the role of commitment: “Knowledge, unlike information, is about beliefs and commitment. Knowledge is a function of a particular stance, perspective or intention” (1995: 58). By instigating commitment, the Studio helped to ensure the nascent network of associations would continue to be remade when the participants returned to their day jobs.

The significance of commitment is also demonstrated in one of the biggest decisions to emerge from the Studio: to change the name of the business from Dr Ed. Amit and his co-founder David had coined the name Dr Ed and were personally attached to it. For several years other members of the management team had suggested the name was a problem, but it wasn’t until the Studio that Amit was open to an alternative:

“It’s not easy to hear…David and I came up with the name 5 years ago…we don’t care about the design, but to rename…we got to that point at the end of the Studio…we were like ‘oh my god no one likes the name’. That was a big emotional place to get to for us personally…”

By confronting ‘concrete’, ‘physical’ situations, in which customers demonstrated genuine distaste, Amit and David became less committed to the Dr Ed name. Following the Studio Joe, the CMO, ran a series of tests on Google to back up the argument for changing the name with quantitative data. Amit was now open to the findings, and this lead directly to the current rebranding.

CONCLUSION: BUSINESS STRATEGY AS AN UNFOLDING NETWORK OF ASSOCIATIONS

In his classic article, Michael Porter characterises strategy as the need to make difficult choices. He argues “with so many forces at work against making choices and trade-offs in organizations, a clear intellectual framework to guide strategy is a necessary counterweight” (Porter 1996). However, the evidence explored here suggests that an intellectual framework is not enough.

Porter characterizes strategy as a linear, analytical process that produces a static set of written materials outlining the agreed direction and set of decisions. Strategy is, in theory, independent of the people, context and environment in which it is conceived. In this view, the strategy document could be shared with an equally competent management team and the same outcomes would be achieved. Strategy development becomes a science, the products of which recede into a ‘black box’ (Latour 1987), thereafter usable by other qualified business ‘scientists’.

However, as the evidence has demonstrated in this case study, the range of outcomes are often contingent and not the result of a linear process. They are the product of an ongoing and complex interaction of people, experiences, artefacts and decisions that plays out over time. In this sense strategy can be seen an unfolding network of associations, not a static, disembodied document.

If we stop thinking about ‘strategy as a document’ and start thinking about ‘strategy as a network’, then this reframes how we think about effective strategy. At the centre of this sits the question of knowledge management. In the ‘strategy as document’ paradigm, it is assumed that formalised knowledge is infinitely transferable. In the ‘strategy as network’ paradigm, it is assumed that knowledge is contingent on participation in the network.

As Stewart Allen explains, knowledge is produced in networks, and therefore not fully transferable between them:

[When] we read knowledge as an emergent phenomenon performed between a range of heterogeneous actors, rather than an entity transferred between individuals across space, we are in a better position to consider the different actors that shape the outcome of knowledge-transfer projects. Knowledge in this sense is transformed and transmuted between different actor-networks rather than transferred as a distinct unit. The form of knowledge that emerges is contingent upon the actor-networks through which it is performed. (Allen 2011)

This helps to explain why participants in the Studio struggled to communicate the nuances of the strategy to people who were not part of the process. The ‘form of knowledge’ they had developed was predicated on the non-replicable network produced through the Studio process.

Viewed from this perspective, the Studio can be understood as a vehicle for initiating, aligning and catalysing a network of associations. By recognizing strategy as a network, the approach helps to focus the ‘web of relations’ between actors. In this light, the distinction between a good strategy and bad strategy is not just its formal content. It is also the quality of these relations, and how coherently the network reproduces itself over time. As soon as relations break down, so does the coherence of the strategy.

The ethnographic research at the heart of the Studio is a critical ingredient, contributing to the network a set of common experiences and insights which strengthen it. The form of knowledge which is produced in the process becomes the foundation for the strategy that emerges. People and outputs become the carriers of the strategy, but only if momentum is maintained.

The Dr Ed strategy is considered successful to date partly because these relations have remained active, strong and coherent. The fact that a senior, cross-functional team engaged in the Studio seems important. If a more junior team had been engaged with little organisational authority the network may have lost steam. Important too is the small, entrepreneurial nature of the business, which has enabled fast, flexible decision-making. This raises questions about how transferable the approach is to larger organisations.

On closer inspection, however, it is less a question of scale, and more a question of whether components of the network (the people and shared resources) have the capacity to deliver the strategy. If the strategy is too ambitious for its components, then relations will break down and it will cease to exist. The trick is getting the right mix between ambition, people and resources. The Dr Ed strategy was ambitious within the context of the organisation because it involved the most senior people in the business. A strategy engaging people with different positions within an organisation needs to reflect those positions.

Prioritising the multiple components of the network also puts our role as ‘strategist’ or ‘researcher’ in context. Rather than an omniscient, objective agent, once removed from everyday business, the strategist becomes another actor with a particular set of skills. Their contributions within and ‘translations’ (Latour, 2007) of the network should not be favoured when accounting for it. Rather the strategy should be defined, understood and evaluated in relation to all its contributing components.

Perhaps the most interesting contribution of the Studio approach is that it invites us to open the ‘black box’ of strategy. In doing so it helps us reappraise what strategy is and break down the false distinction between strategy in theory and strategy in practice. Instead of smoothing over the inconvenient contingencies of strategy in practice, the Studio highlights these dynamics and seeks to control and influence them to produce more successful and predictable outcomes.

Tom Hoy: A founder at Stripe Partners, Tom has spent 10 years advising organisations like Diageo, Samsung and the NHS on complex marketing, innovation and strategy challenges. Tom specialises in combining new academic thinking with emergent technologies to create experimental research processes, and contributed to the co-creation methodology at Promise (no C-Space/Omnicom).

Tom Rowley is a founder at Stripe Partners and heads up the strategy practice. Throughout his career Tom has helped global organisations to develop and activate brand and innovation strategies rooted in deep human insight. Before co-founding Stripe Partners, Tom headed up the cultural insight function at Added Value.

REFERENCES CITED

Allen, Stewart. “Barefoot Engineers: The Non-Mobility of Knowledge in a Knowledge-Transfer Project.” Anthropology Matters (2011) (http://www.anthropologymatters.com/) Accessed June 10, 2016

Callon, Michel. “Some elements of a sociology of translation: domestication of the scallops and the fishermen of St Brieuc Bay” In Power, action and belief: a new sociology of knowledge edited by John Law, 196-223 London: Routledge, 1986

Ingold, Tim. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. London: Routledge, 2010

Latour, Bruno. Science in Action. Harvard: Harvard University Press, 1987

Latour, Bruni. Reassembling the Social. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007

Law, John. Actor Network Theory and Material Semiotics, (2007) (http://www. heterogeneities. net/publications/Law2007ANTandMaterialSemiotics.pdf) Accessed June 10, 2016

Hirotaka Takeuchi and Nonaka. I. The Knowledge-Creating Company. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995

Polanyi, Michael. The Tacit Dimension. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2009

Porter, Michael. “What is strategy?” in Harvard Business Review. (1996) (https://hbr.org/1996/11/what-is-strategy) Accessed June 10, 2016

Simon Roberts and Hoy, T. “Knowing that and knowing how: towards embodied strategy” in EPIC proceedings 2015 (2015) https://www.epicpeople.org/knowing-that-and-knowing-how-towards-embodied-strategy/