The ability to lead organizational and cultural change has never been a more critical factor for success in business than today. With renewed urgency many executives ask what do with their company culture(s): “Why can’t we build organizations that are more innovative, inspiring, and more agile – and why do our change initiatives typically fail?” Based on project engagements where questions like these have been a focal point, this paper aims to shed light on the conditions and role of business anthropology to take active part in enhancing organizational change programs. Through concrete examples, it discusses central challenges on how we as ethnographers can strengthen our approach when navigating in change programs – not only in terms of how we decompose and diagnose culture (telling companies what they should not do) – but more importantly on how to play an active role in leading the way and tackling complexity through positive enablers of change.

INTRODUCTION: TAKING UP NEW CHALLENGES – GETTING OUT OF OUR COMFORT ZONES

The ability to lead organizational and cultural change has never been a more critical factor for success in business than today. In a world of unprecedented change and competitiveness companies need to look closer at their organizational performance to assure that the company and its employees are geared to take up future challenges and deliver the expected returns.

At the same time – with the rising complexity of companies – organizational culture is increasingly becoming a black box and thus harder for companies to understand, predict and transform. Organizational culture has become a bloody battlefield where culture is often presented as a slowing drug that works against top management’s ambitions of increased and sustained revenue and profit. In such a climate business anthropologists working as consultants are asked to demonstrate renewed relevancy and impact of their work to help clients understand, control and drive cultural change.

Approaches to change management and organizational performance have been extensively described in the business literature within the last twenty-five years primarily driven by disciplines such as business strategy, human resource management, and organizational psychology (Hoffsted 1990, Schein 1994, Kotter 1996). The increased focus and professionalization of organizational change initiatives naturally raised the attention of the softer sides of change in the business environment where the hard facts made it evident that there was – and still is – big money in measuring and putting corporate culture on formula to enhance due diligence processes, downsizings, restructurings and improve hit rates for successful mergers and acquisitions (Mobley, Wang and Fang 2005). The typical issues on organizational culture in this literature have concentrated on how to make the best cultural fit when companies merge, and how to make transformations stick in the organization, avoiding human and cultural resistance to change? Most of the literature stresses the importance of the human and cultural sides of change yet few pieces offer substantial guidance on how to really observe, understand and take advantage of the unique cultural DNA and the building blocks that drive change.

Looking at our professional field, great ethnographic contributions have been made on organizational studies, work culture and production rites (e.g. Van Manen 1979, Orr 1996) but the field of change management1 has not yet received acknowledged attention among a wider crowd of anthropologists and ethnographers; little emphasis has been placed on how our methods and work can be used to better support and lead lasting transformations in corporate environments. One obvious reason for this might have to do with the traditional and widespread passion for going native and making sense of everyday people’s life and work and not on actually transforming peoples’ life modes and behaviors.

We have the methods and tools for uncovering practices and tacit needs among everyday life (Schwarz, Holme, Engelund 2009) but what is less described is how to make these insights applicable for especially top management to take decisions on. As Nafus and Anderson (2006) argue, the field of industrial ethnography tends to use a certain rhetoric or claim of a special relationship to “real people”. I would argue that this rhetoric and passion for the “real people” approach in the case of organizational ethnography has made us biased even skeptical towards entering the management rooms where we are faced with questions like: “Which parts of our everyday culture are slowing our growth and why don’t we just get rid of the employees who are not willing to make the change?” Within our field, being part of change management programs seem to connote a sense of “being in bed with the enemy” in contrast to representing and painting the lives of the real people whether these are workers in the production lines, R&D employees, or the hardworking sales force. Our special relationship to “the real” everyday life has made us reluctant to deal with change programs because they often have significant consequences for the culture or the “real people” despite the fact that they hold the potential of delivering sustainable business results for the organization. We hereby reduce our roles to “poets of everyday life” at the expense of opening new opportunities for our field. The consequence of what I would term “the management fear” is that our discipline so far left has the job of understanding and leading cultural change to management theory and consultants with limited human factors understanding: As a result organizational culture has been “managementized”. The positive thing is that the situation has made organizational culture easier to measure but has far from given the sufficient guidance to why changing mindsets and behaviors rarely succeeds with this generalized approach.

Using actual project engagements and experiences as the guiding point, the paper therefore aims to shed light on the conditions and role of business anthropology to take active part in enhancing organizational change programs. This paper seeks not to provide a silver bullet formula on organizational culture rather it explores the challenges and opportunities for business ethnography in organizations where the need for tackling and harnessing cultural complexity continues to grow.

In the discussion I seek to address the following questions: Can business anthropology play a more active role in highlighting the positive enablers of change in order to make people work together more effectively and efficiently? How can we find the balance between cultural diagnose and cultural change without loosing our ethnographic integrity? Acknowledging that such questions require a hands-on approach the paper will build upon and present concrete project challenges and learnings from the perspectives of both client and consultants.

SETTING THE SCENE

In the summer of 2009 my consulting firm conducted a research and consulting project for an international engineering company working within the building and transport sector. After some challenging years of adversity the executive management wanted to reenergize the company and become more profitable by building a stronger profile and brand. The aim of the business-to-business project was to make an external analysis of how the company’s key customers perceive the company and an internal analysis of the company culture and what drives change among the employees. In essence, a project helping the client better understand and improve the interface between the needs of the company’s customers and the culture and behavior of the employees. The direct client was the company’s executive management and HR-department.

In order to consult the company on which cultural building blocks were of greatest importance to boost pride, creativity and performance in the organization, we were deeply involved in the everyday lives and narratives among hardworking engineers across several departments and locations. The challenge was not only to decode the cultural patterns of the organization rather it was the derived implications of this analysis that created central learning experiences on how to enter and engage in new change-relationships with our clients.

During a period of more than two months a team of five ethnographers took part in and observed different organizational workarounds, client interactions, lunch breaks, sales meetings, and daily project assignments as well as interviewing and observing key clients. The research design took focus on five selected areas covering various levels of the organization on both project employee, middle management and executive level where we followed the monthly strategy meetings. In conversations with the executive management and HR-director we agreed that an open and deep approach was needed to get beyond what was defined as the yearly “generic employee satisfaction survey” which in reality revealed very little about the key characteristics and DNA of the company’s culture.

AN ETHNOGRAPHIC APPROACH TO CHANGE MANAGEMENT

In order to show where we as a business discipline could have a more value-adding role to play, I have chosen to emphasize on selected key challenges for business ethnographers to learn from, acknowledging that a paper will not be able to cover all aspects of the project satisfactorily. I will discuss three central challenges: first, the challenge of unlocking the black box and clarifying the change ambition and the cultural problem to be solved, secondly, showing the evidence of the cultural DNA to create understanding and commitment, and thirdly, enabling the positive elements for change to ensure visible results instead of building additional conflicts and trenches.

Unlocking the black box of culture: Focus on the core problem to solve

Obtaining a stronger company culture may sound as an imperative in all change programs but a strong culture in itself might not only bring immense advantages. A strong company culture might benefit from consistent values but might be confronted by inflexibility because people get used to working in certain ways where they passively build a protective instinct towards change. One of the most important challenges when working on such a broad field is to help the client enhance the understanding of the cultural problem to be solved and that you share the basic assumptions and definitions of culture in order to change it. One central learning here is – in contrast to well-defined financial and technical terms – that culture is an abstraction that for many leaders has become a garbage can of elements they found hard to fit anywhere else.

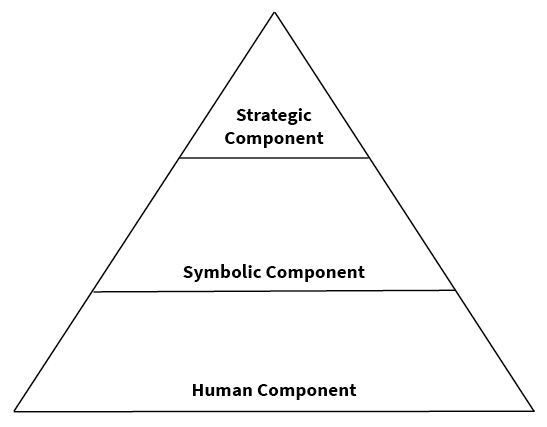

When leaders speak of making a cultural change they most likely refer to a mix of beliefs and assumptions triggered by a combination of issues like decline in sales, lost market share, decreased employee retention, or slower working processes. When working on cultural change projects we must use our experience and break down these assumptions into more concrete points to understand why there is a need for making this change and in which parts of the company the issues are most dominant. By recognizing the actual business problem we can make a clearer link between culture, business performance, and leadership. Inspired by Schein (1994) and Jordan (2003) we used a framework with three different components of organizational culture to guide discussions and clarify success criteria (see model) hereby ensuring that cultural change was not solely a matter of traditional definitions such as tacit values, beliefs and behaviors. The three components are the strategic component, the symbolic component, and the human component. The strategic component describes the company’s values, business strategy, vision and mission. The symbolic component describes structures, processes, office layout, artefacts, and shared stories. The human component relates to unarticulated values, emotions and behaviors, which are the everyday drivers of change and engagement among employees. By applying this framework we made it easier to articulate and create a shared understanding of the core problem to solve with the client team – making the link between business strategy and desired behavior more clear. Since culture and leadership in this case are two sides of the same coin the framework also gave the leaders a way of conceptualizing the culture in which they as leaders are embedded.

Schein argues that simply because culture is so hard to create and manage, today’s leaders need to better understand the dynamics of organizational culture if they don’t want to become victims of it. Our challenge as ethnographers here was that we are trained that everything is relevant, are suckers for social complexity and claim to have a special link to the ‘real people’. If we want to ensure greater business impact, our thinking and communication simply need to be more applicable by making clearer links between culture and business strategy in order for the company to relate to and act upon.

Model: The three components of organizational culture guided the company’s understanding of how strategies, symbols, and behaviors are inextricably interconnected when leading cultural change.

Show the cultural DNA, don’t tell it

Establishing a shared understanding of definitions and frameworks of culture provides an important starting point in change management projects. In this case, these discussions initially took place with the executive management group. But one thing was to agree on definitions and key areas of investigation – it was much more challenging to establish a shared understanding of the analyzed company DNA and the consequences of it when we mirrored this up against the external analysis of the company’s customers. As mentioned, we were asked to describe the company from both an internal perspective – by focusing on employees, interactions, and workplace rites – as well as an external perspective investigating how the company’s clients defined the brand, services, and communication.

The triangulation approach was clearly challenging since it urged the need for identifying improvement areas across the predefined themes and categories. Through extensive observations, interviews, interaction mappings, and perception exercises we found it initially hard to communicate the findings. After our first briefing meetings the client told us that they had concerns that our approach was too abstract and fluffy to communicate, and in the following weeks we realized that one reason for this had to do with the fact that the communication and symbolic language in the particular engineering culture was “silent” and extremely subtle.

Modern organizations and workplaces are among the most complex ritual systems ever developed (Auslander 2003) and studying this particular company where tacit rituals, deep concentration and passion for the detail were dominant features challenged us to be more intelligent in the way we investigated, analyzed and communicated the cultural building blocks. In order to avoid the claim of being too abstract we had to show clear evidence of our findings instead of just explaining them. Theoretically, we found inspiration within the classic pieces of symbolic anthropology (Geertz 1977). Working in such highly structured and complex engineering environments made it important to provide a narrative the employees could relate to and identify with but also a narrative and an idiom that stressed the burning platform and why change was needed. We worked with a narrative of a company having lost its sense of purpose and its original sources of energy by comparing the culture to mechanical metaphors such as different car models and brands. In our interviews with the engineers we had found that communication around the company values and characteristics was remarkably easier when talking about machines and mechanics instead of talking about abstract things like what they “felt characterized the company culture”. The synthesis of these perceptions became a concrete story and visualization showing the cultural DNA that lifted up the story from the realm of practicalities of everyday affairs – and provided a metasocial commentary of collective existence. The concrete idiom made it powerful, fun and easy to share, discuss and communicate among the employees. Combined with other findings communicated in visual and humoristic ways – one being that the engineers had a self-image of being active sales people; however we found that they performed what we termed “aggressive sales by waiting by the phone” only waiting for their customers to call them – the narrative initiated a process of self-awareness that slowly became a story the employees told themselves about themselves.

In order to put some harder and more measurable facts on the initial findings from the observations and interviews we decided to qualify these findings through an internal survey with both closed and semi-closed questions. We chose this approach for two reasons: first, because communicating evidence from employee interviews cannot be done with video due to confidentiality and therefore not made as “real” as we tend to do when documenting consumers’ homes and everyday life. Secondly, because showing the quantifiable volume of the insights made the arguments and burning platform for why change was needed measurable and more evident. As a side effect, the survey results also turned out to be effective means of communicating the findings in combination with mechanical metaphors because the numbers and charts where easier for most of the engineers to relate to and understand since these were part of their everyday language.

The challenge for the ethnographers here was to reduce complexity and make findings on organizational culture(s) concrete and easy to communicate so they can be shared, and challenged, hereby making them part of the everyday language and the change journey. Without explaining the concrete consequences of these narratives and linking these to the business strategy, the stories can unintentionally end up glorifying the status quo making adaption to external changes in the market somebody else’s problem.

Building change on cultural energy and everyday heroes

What separates humans from animals is not that she has a language and can communicate. What separates humans from animals is the ability to think about the future. As humans we can make projections and scenarios of what we desire or fear will happen in future times. This makes us both anxious and opportunistic creatures. The Swedish neurologist David H. Ingvar (1985) has investigated why alcoholics find it difficult to change behavior because of lack of neural machinery and imagination for projecting a better future. Ingvar indicates that our ‘inner future’ is made of our past and present experiences – in essence that imaging a better future requires an ability to remember the past. Having lived as alcoholic abusers most of their life has made this memory the dominant story of the past where the scenario of a future without alcohol gives a sense of being part of a science fiction movie. The analogy is striking when it comes to leading change management projects: If the company culture has been stable and delivered satisfactory results over a decade (i.e. the memory of stable alcohol routines) it has limited cognitive repertoire for anticipating or imagining a different future. People will most likely – in the search for comfort and certainty – continue doing what they do slowly falling into the old rhythms and “start drinking again”. If not provided with a relatable vision and story where you can learn what the new future will bring the greater is the likelihood for change projects to fail. If the story about where to go doesn’t resonate and link with the company’s heritage and cultural identity the project will most likely be excluded like a foreign body.

An important learning for us here was to avoid making this vision and story about change solely about and for the executive management team if we where to succeed and engage the employees – we had to find local ambassadors, teams and networks who could help drive the change at different levels in the organization. During our research we identified central “knowledge grids” of unofficial opinion leaders who were highly respected for their engineering expertise and experience. This gave us inspiration to use these everyday heroes as a way to boost pride and tell the story about the transformation. This was not a story communicated in traditional business language of increased revenue or profit, rather it focused on the benefits of improving creative skills, cooperation, and technical expertise to deliver greater and more challenging achievements; putting the engineers’ mark on the world at the centerpiece. In contrast to the executives’ belief – who where of the opinion that it would be almost impossible to get these opinion leaders on board since they per definition were reluctant to change – we worked with an initiative to win the opinion leaders because they were setting the informal agendas and challenging the strategic component of culture, described earlier. This way we wanted to make sure that local heroes – who could be mediators of past and future – could drive the transformations. And in order to ensure that the insights and vision was properly negotiated and discussed bringing employees along the journey, we hosted a number of workshops and exercises with around hundred middle managers and key employees where we shared and tested ideas for change ensuring that this was not a “do as the management says” kind of process. Since substantial changes of the culture can take years these processes need to be continuously repeated, measured and developed to ensure employees understand and feel ownership to the direction and what it means for them.

Since every organization has unique characteristics and heroes, the challenge for ethnographers is to be more strategic in the way we identify and work with the enablers of change and point out the ones who can best drive the change, who can take ownership of the vision, translate it to concrete initiatives and create visible business results. Anyone leading a major change program must therefore take the time to think through the “story” and link the story to the existing foundation and DNA of the company and to explain that story to all of the people involved in making change happen. Business ethnographers can help bridge past and future by showing not only how cultural transformations has taken place historically but should also become much stronger communicators of where to go and not only from where one should departure. Through our deep understanding of the corporate DNA and what transforms the culture we could actually have a more prominent role in helping companies taking step-by-step approaches showing how to get there.

CONCLUSION: PERSPECTIVES ON THE ROLE OF ETHNOGRAPHY IN CHANGE MANAGEMENT

The paper has described how understanding and changing organizational culture is a key success factor in today’s business. Yet, as a discipline ethnography has so far left the job to management consultants with limited human factors understanding to drive this field. As a consequence organizational culture has been “managementized” where the focus on the individuals (e.g. through traditional employee satisfaction surveys) and not on the interaction and shared beliefs between people has made it complicated for companies to really find the corporate energy that will enable a lasting change. Cultural change does not only take place in corporate training programs for selected employees. Large change programs require all employee levels are involved and they require a deep understanding of how to take advantage of what really happens when employees influence and bump into each other. In this context, I have argued that companies can gain better and more sustainable results, if we as business anthropologists want to take a more active role in advising on how to identify and work with positive enablers of change. This requires that we see ourselves not only as analysts but also as advisors who really dare to initiate and drive changes that have significant consequences for the employees. Consequences that sometimes might challenge our professional comfort zones and our special link to “real people”. I have not argued for an already out there silver bullet solution instead that business anthropology should reclaim the space we’ve lost and are losing to other disciplines.

The paper has focused on three selected challenges for business ethnography in enhancing change management programs and taking a more thought-leading role. The challenge of becoming better at understanding and delivering on the core problem to solve – linking business strategy with culture, the challenge of communicating the cultural DNA in powerful yet concrete ways that both create identification and a narrative for change, and lastly the way to turn the everyday heroes in the organization into drivers of change in order to create lasting results at various levels in the organization.

Mads Holme is manager at ReD Associates’ Copenhagen office. He holds an M.A. in Ethnology and Rhetoric from the University of Copenhagen.

NOTES

1 A change management project in this context refers to a structured approach to transition an organization from one state to another and where the behavioral change of the employees make up the outputs of the organization

REFERENCES CITED

Auslander, Mark

2003 “Rituals of the workplace”. Sloan Work and Family Research Network. http://wfnetwork.bc.edu/encyclopedia_entry.php?id=254 (accessed 16 August 2010).

Geertz, Clifford

1973 “Deep play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight.” In: The interpretation of cultures. New York: Basic Books.

Hoffsted, Geert, Neuijen, B., Ohavy, D.D., and Sanders G.

1990 “Measuring Organizational Cultures: A qualitative study across twenty cases.” Administrative Science Quarterly. Vol. 35 286-316.

Ingvar, David H.

1985 “Memory of the future: an essay of the temporal organization of conscious” awareness. Hum. Neurobiology4:127-136.

Jordan, Ann T.

2003 Business Anthropology. Prospects Heights, IL: Waveland Press.

Kotter, John P.

1996 Leading Change. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Press.

Mobley, William; Lena Wang and Kate Fang

2005 “Organizational culture: Measuring and developing it in your organization”. China Europe International Business School. http://www.ceibs.edu/knowledge/ob/9297.shtml (accessed 16 August 2010).

Nafus, Dawn and Ken Anderson

2006 The Real Problem: Rhetorics of Knowing in Corporate Ethnographic Research. Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings. Pp. 244-258. DOI: 10.1111/j.1559-8918.2006.tb00051.x

Orr, Julian

1996 Talking About Machines: An Ethnography of a Modern Job. Ithaca, NY: ILR Press.

Schein, Edgar

2004 Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Schwarz H, Holme M, Engelund G.

2009 “Close Encounter: Finding a New Rhythm for Client-Consultant Collaboration.” Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings. Pp. 29-40 DOI: 10.1111/j.1559-8918.2009.tb00125.x.

Van Maanen, John

1979 “The Fact of Fiction in Organizational Ethnography.”

Featured Image by Robert Katzki